|

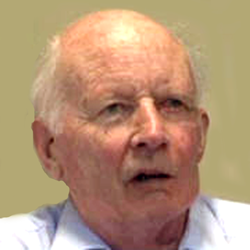

Robin Cocks [*]

1938 - 2023

It is with great sadness that we report our colleague, Robin Cocks, passed away in the early hours of this morning (February 5th). Robin’s contribution to brachiopod research was immense in both its breadth and depth. Robin leaves a massive legacy of taxonomic work; he promoted the application of brachiopods in palaeobiogeography, palaeogeography and palaeoecology with a strong focus on the Ordovician and Silurian. Many of us were hosted by Robin on visits to the collections in The Natural History Museum; the 4th International Brachiopod Congress in London in 2000 was a wonderful event both scientifically and culturally. Our community has lost a giant. A full obituary is following.

David Harper and Lars Holmer

[*] Leonard Robert Morrison Cocks

Robin Cocks was arguably the world’s most distinguished student of brachiopods, and his death on February 5 deprives the scientific world of a lifetime of expertise and scholarship. During his many years at the Natural History Museum, he rose to become Keeper of Palaeontology (1986-1998), but never lost his enthusiasm for science – indeed, he was still working on new papers a few weeks before he died. It seems unlikely that his equal will be seen again.

Robin was of the generation that was young during WW2. After a gruelling time in a preparatory school he was educated at Felstead School. He was obliged to do National Service in the years that followed. He served his time in Malaysia, with the Royal Artillery, where the fierce sun took its toll on his typically English fair complexion (this may be implicated in the skin cancers he suffered from later in life). Oxford followed, and after gaining a first-class honours degree in geology he completed a DPhil (1965) on Silurian rocks and faunas supervised by Stuart McKerrow, who later became a friend and colleague. When he was appointed in the same year to the British Museum (Natural History) (as it was then) as Scientific Officer, Howard Brunton was also taken on to the staff. Apparently, they were such outstanding candidates that both were employed, which seems unimaginable today. Brunton was assigned the Upper Palaeozoic brachiopods and Cocks the Lower Palaeozoic. Robin was promoted to Senior Scientific Officer and then Principal Scientific Officer as his career progressed, and Ellis Owen completed the brachiopod ‘team’ with his expertise in Mesozoic species. It is sad to reflect that the brachiopods once had three full time specialists in the “BM” (as it was known) where now there are none.

From his appointment onwards a steady stream of systematic papers on brachiopods were published from Robin’s hand that continued until last year. By the mid 1990s he had become as expert on Ordovician as Silurian brachiopods, and eventually claimed to have named a new genus for every letter of the alphabet. His compass extended globally, from a secure base in the Silurian (Llandovery) of Britain, to a series of papers on the Ordovician of Kazakhstan with his long-time collaborator. Leonid Popov. Such monographs may not be the height of fashion, but sthey will endure. His pioneering research also involved studies of brachiopod-dominated biofacies, including the seminal paper on the composition and structure of Lower Silurian marine communities published jointly with Ziegler and Bambach in 1968. Robin’s long-term research collaborator also included Rong Jiayu, and together they investigated both strophomenide morphology and taxonomy, as well as the global palaeobiogeography and biodiversity patterns in brachiopods during the Early Silurian recovery period after the Late Ordovician mass extinction. At the same time, Robin was always anxious to describe himself as a geologist, and he enjoyed sorting out the stratigraphy of the Silurian rocks in Britain. He and McKerrow spent summers in Newfoundland attempting to apply the relatively new science of plate tectonics to the complex geology of that island, where the story of the vanished ocean Iapetus is preserved. Robin later became a central figure in the debate about exactly where to draw the boundary between the Silurian and Devonian Periods. A definitive volume of papers of the ‘BM Bulletin’ edited by Robin in 1990 helped secure the international retention of the British names of the standard chronostratigraphic Silurian subdivisions.

A recurring theme in Robin’s research became the reconstruction of ancient geography when it became clear that continental distributions were very different in the Palaeozoic from those at the present day. This research burgeoned in the 80s and 90s in conjunction with the present writer, since brachiopods and trilobites taken together allowed new insights into the ‘signatures’ of ancient continents and their margins. After Robin reached the mandatory retirement age in 1998 he continued this theme, particularly with Professor Trond Torsvik in Norway, whose computer modeling permitted a more sophisticated treatment of ancient geography. Many new continental reconstructions were published during the first decade of the 21st century. The collaboration was summarized in a book published in 2017 by Cambridge University Press that has already become indispensible to palaeontologists and tectonic geologists around the world.

During Robin’s time as Keeper of Palaeontology in the Natural History Museum he maintained a generally light touch, preferring to let his best scientists pursue their own line of research without his intervention, so long as they produced the ‘goods’, mostly in the form of published papers. Judging by external recognition it could be said that the Palaeontology Department at that time was at the zenith of its reputation, for example, having two Fellows of the Royal Society (later three) elected from the staff, which was previously unequalled. As an administrator, Robin liked to get the official stuff out of the way quickly – so that he could return to his beloved brachiopods. This businesslike approach sometimes resembled brusqueness, and his deputies the ammonite specialists H. G. Owen or M. K. Howarth occasionally had to tactfully intercede. Despite his administrative burden Robin somehow managed to make huge contributions to the Brachiopoda for the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology – at that time edited by the forceful Sir Alwyn Williams. This was a testament to his organizational skills as well as his scholarly command and extraordinary memory. Over many years he had gathered specimens of the type species of brachiopod genera that came together in this definitive summary, which is likely to remain current for the foreseeable future.

Robin Cocks served many academic societies and international committees. On the palaeontological front he is the only person who has been president of all the appropriate British learned societies. He was president of the Palaeontological Association (1986-1988), a group with which he was concerned from its early days, and helped towards its current status as the leading organization of its kind in Europe. He was president of the Palaeontographical Society (1994-1998), which published several of his major papers on brachiopods. The pinnacle of his service to the geological community was arguably as president of the Geological Society of London (1998-2000), where he had previously been responsible for important decisions on the independent future of its publishing arm that made a vital contribution to the survival of the Society. Finally, he presided over the Geologist’s Association (2004-2006). On the international level he was a voting member of Silurian Subcommission of the IUGS for many years, and was a Commissioner of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature for two decades (1982-2002).

Robin had to cope with health problems that might have deterred a lesser soul. He had successful treatment for a facial cancer in 1984, but the radiotherapy from the procedure inadvertently ‘killed’ his jawbone, and in 2006 he was given an operation to replace it with an artificial substitute. Unfortunately, the nerves serving to enervate one side of his face were irretrievably damaged during the operation, paralyzing this area. Many secondary problems arose from this unfortunate accident, not least with voice projection, all of which he ignored with great courage. To his friends, he seemed indestructible during his ‘retirement’ years, when he did not allow any health impediment to interfere with his research: if anything, the brachiopods and palaeogeography served to keep him going.

Robin’s contribution to science was recognized by the Geological Society by the award of their Coke Medal in 1995, the Dumont Medal of Geologica Belgica in 2003, and the Lapworth Medal of the Palaeontological Association in 2010. He was awarded an OBE in 1999. Away from his work, he was a devoted family man. He is survived by his wife Elaine (née Sturdy) whom he married in 1963, his three children and eight grandchildren.

Richard Fortey, Lars Holmer and Leonid Popov

|