Contents

[1. Geological introduction] [2. Sample locality and stratigraphy]

[3. Taxonomy, biostratigraphy and palaeobiogeography of the genus Frambocythere]

[Bibliographic references] [Appendix]

Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Ciências, Centro de Geologia, Campo Grande, C-6, 3°, P-1749-016 Lisboa (Portugal)

3 Impasse des Biroulayres, 33610 Cestas (France)

Geology Department, Faculty of Science, University of Isfahan, Isfahan 81746-7344 (Iran)

Manuscript online since September 17, 2012

[Editor: Michel ; copy editor: Christian C. ;

language editor: Stephen ]

The limnic ostracode Frambocythere tumiensis zagrosensis subsp. nov. (Limnocytheridae, Timiriaseviinae), has been found for the first time in Iran. The strata containing this species are in the lower part of the Tarbur Formation in the interior Fars of the Zagros Mountains. The Late Maastrichtian age is indicated by rudists, larger foraminifers (Omphalocyclus macroporus, Loftusia spp.) and planktonic foraminifers (Contusotruncana contusa-Racemiguembelina fructicosa Zone) present in the upper part of the Tarbur Formation. The Maastrichtian age is confirmed by the occurrence in the same strata of the charophytes Platychara shanii, Peckichara cristellata and Stephanochara cf. producta. The genus Frambocythere , 1980, was until now known mostly from the Upper Maastrichtian to Middle Eocene of southern Europe, India and China, as well as the Albian of the Democratic Republic of Congo. The presence of Frambocythere gr. tumiensis in Iran is therefore a newly recognized link between southern Europe and the Far East (China).

Limnic ostracodes; Upper Maastrichtian; Iran; Zagros; taxonomy; palaeobiogeography.

J.-P., H., A. & S. (2012).- Presence of Frambocythere , 1980, (limnic ostracode) in the Maastrichtian of the Zagros Mountains, Iran: a newly recognized link between southern Europe and the Far East.- Carnets de Géologie [Notebooks on Geology], Brest, Letter 2012/02 (CG2012_L02), p. 173-181.

Présence de Frambocythere , 1980, (ostracode limnique) dans le Maastrichtien des Monts du Zagros, Iran : un nouveau relais entre l'Europe méridionale et l'Extrême-Orient.- L'ostracode limnique Frambocythere tumiensis zagrosensis nov. subsp. (Limnocytheridae, Timiriaseviinae) a été trouvé pour la première fois en Iran. Les niveaux contenant cette espèce proviennent de la partie inférieure de la Formation de Tarbur dans les Fars intérieurs des Monts Zagros. L'âge maastrichtien est donné par les rudistes, les grands foraminifères (Omphalocyclus macroporus, Loftusia spp.) et les foraminifères planctoniques (Zone à Contusotruncana contusa-Racemiguembelina fructicosa) dans les niveaux de la partie supérieure de la Formation de Tarbur. L'âge maastrichtien est aussi conforté par la présence dans les mêmes niveaux des charophytes Platychara shanii, Peckichara cristellata et Stephanochara cf. producta. Le genre Frambocythere , 1980, n'était jusqu'à présent connu que du Maastrichtien supérieur à l'Éocène moyen en Europe méridionale, Inde et Chine, ainsi que dans l'Albien de la République Démocratique du Congo. La présence de Frambocythere gr. tumiensis en Iran est donc un nouveau relais entre l'Europe méridionale et l'Extrême-Orient (Chine).

Ostracodes limniques ; Maastrichtien supérieur ; Iran ; Zagros ; taxonomie ; paléobiogéographie.

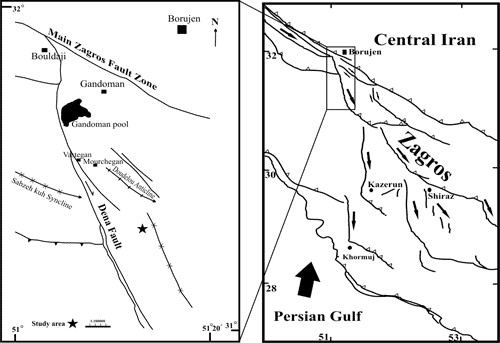

The Borujen area is located in the eastern Zagros Mountains, in the interior Fars, which were formed as a result of the closure of the Neotethyan Ocean during the Late Mesozoic and the Cenozoic (Fig. 1 ![]() ).

).

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Figure 1: Location map of the studied section, 48 km S of Borujen, Iran.

During the Maastrichtian, an active carbonate platform with numerous rudist build-ups appeared contemporaneous with sea-level change in the eastern part of the Neotethyan realm (Zagros region). This succession, called the Tarbur Formation, extends across the internal Fars and Lurestan and is formed mainly of siliciclastic rocks comprising shales, sandstones and polygenetic conglomerates, and some carbonate units with rudist lithosomes sometimes incorporating corals, other bivalves, gastropods and algae.

The name Tarbur Formation was proposed by & (1965) for a series of limestones, rudist build-ups and shales overlying the Gurpi and Sachun formations. Although the Tarbur Formation was deemed to be a single formation by & (1965) and was re-described as such by other authors (, 1976; et al., 2005) from SW Iran, it is represented by varied and complex rock associations. In its type locality in Tarbur village, southern Iran, this formation consists of limestones with larger foraminifers and rudist lithosomes.

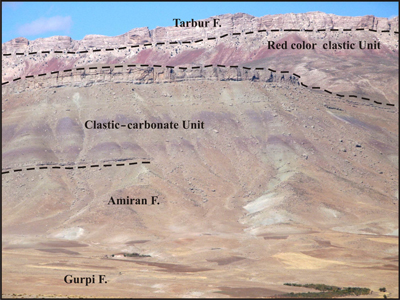

In the study area, the Upper Cretaceous sedimentary succession is rather monotonous and consists exclusively of shallow-water carbonates and shales. The oldest sediments of the area crop out at Tang-e-khoshk, which consists of silty shales and thin-bedded limestones of the Lower Cretaceous Gadvan Formation. The studied section, with a thickness of about 1,100 m, is situated NW of the Semirom plain and S of Borujen. It consists of Upper Cretaceous sedimentary rocks, the Gurpi, Amiran and Tarbur formations.

The Gurpi Formation is composed of shales, calcareous shales and sandstones. It contains abundant planktonic microfossils of Santonian-Campanian age. Its lower contact with the Ilam Formation and its upper contact with the Amiran Formation are both gradational.

The main lithology of the Amiran Formation is ophiolite-derived siliciclastic turbidite intercalated with siltstones, carbonate sandstones and shales. The grains include chert, quartz, volcanic and limestone rock fragments and radiolarians. The Amiran Formation is a thickening-upward sequence which contains fining-upward cycles indicating deposition by turbidity currents. The formation is of Late Cretaceous age and its upper contact with the Tarbur Formation is gradual. The Amiran Formation is the result of tectonic sedimentary processes related to the Laramian geodynamic event (, 2004).

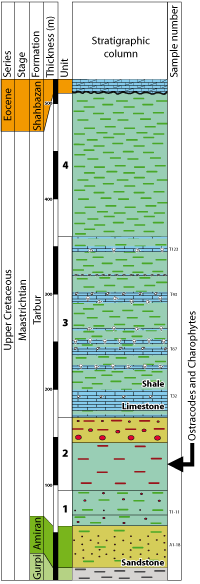

The Tarbur Formation consists of limestones, shales and sandstones with a total thickness of about 920 m. These units generally show lateral changes in thickness, composition, density and facies. The limestones contain a rudist reef facies with larger foraminifers, such as Loftusia spp. and Omphalocyclus macroporus (, 1816). These limestones were deposited on a carbonate platform that was eroded by a meandering river during a eustatic lowstand. The presence of rudist debris and larger foraminifers indicates a photozoan assemblage and suggests tropical conditions. The base of the formation is made of fine-grained deposits with massive reddish brown shales and very thin-bedded sandstones. This layer proved rich in charophytes and ostracodes, which are important for dating these sediments.

The microfossils described here come from a reddish brown shale exposed 7 km SW of Gerdbisheh village (beside the Borujen-Lordegan road) about 48 km S of Borujen. In this section, the Tarbur Formation is overlain with an erosional contact by the Shahbazan dolomites of Eocene age. On the basis of lithological variation, we have subdivided the Tarbur Formation into four parts, from base to top:

The exact age of the Tarbur Formation is not well established. & (1965) assigned a Campanian-Maastrichtian age and other authors (, 1976; et al., 2005) dated Unit 3 as Late Maastrichtian based on the occurrence of the larger foraminifers, Orbitoides media (d', 1837), Siderolites calcitrapoides , 1801, Omphalocyclus macroporus and Loftusia spp. Rudists also support a Late Maastrichtian age ( et al., 2010). Unit 4 contains planktonic foraminifers which characterize the Contusotruncana contusa - Racemiguembelina fructicosa Zone of Late Maastrichtian age.

In the studied level (Unit 2) the absence of stratigraphically important benthic foraminifer taxa (especially Orbitoides) precludes better stratigraphic resolution. Unit 2 is certainly Maastrichtian based on the presence of the charophytes Peckichara cristatella & , 1977, and Platychara (Chara) shanii ( & , 1939) & , 1976, cf. Stephanochara producta , 1995 (identification E. and in et al., 2010). For the first time in Iran, this level has yielded the non-marine ostracode Frambocythere tumiensis zagrosensis subsp. nov.

Class Ostracoda , 1802

Subclass Podocopa , 1866

Order Podocopida , 1866

Suborder Cytherocopina , 1850

Superfamily Cytheroidea , 1850

Family Limnocytheridae , 1938

Subfamily Timiriaseviinae , emend & ,

1980

Genus Frambocythere , 1980

The genus Frambocythere was erected by (in & , 1980), with the type species Frambocythere tumiensis (, 1978), from the Upper Maastrichtian of Spain. The genus is characterized by its small size (less than 0,600 mm), the presence of two antero-dorsal vertical sulci, ornamentation of small pustules ("raspberry-like"), and posterior conical spines. The right valve is generally larger than the left (inverse overlap) and sexual dimorphism is pronounced, with a strong posterior widening of the posterior half in females, forming a brood cavity. Some morphotypes (or subspecies ?) can be completely smooth, as in Frambocythere cf. tumiensis ferreri (in , 1980) and Frambocythere tumiensis apleri (, 1978), or partly so, as in Frambocythere tumiensis ferreri , 1980 (, 1991). Up to now, nine species and subspecies have been described and two tentatively assigned to known species (Appendix).

Frambocythere tumiensis zagrosensis subsp. nov.

Derivatio nominis: From the Zagros Mountains, type area.

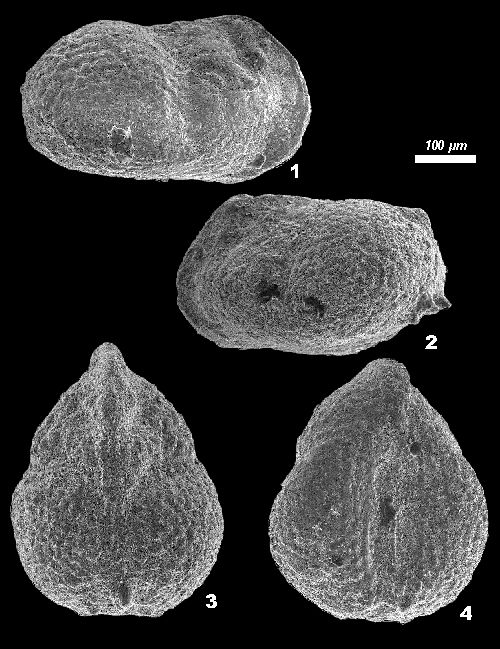

Holotype: Female carapace (Pl. 1, fig. 1 ![]() ) deposited in the collections of the Geology Department, Faculty of Science, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran. Paratypes:

four female carapaces deposited in the collections of the Geology Department, Faculty of Science, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran.

) deposited in the collections of the Geology Department, Faculty of Science, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran. Paratypes:

four female carapaces deposited in the collections of the Geology Department, Faculty of Science, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran.

ZooBank reference: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:70180DC1-2624-4505-943C-48D1B036A0FF

Type locality: 7 km SW of Gerdbisheh village (besides Borujen-Lordegan road) about 48 km S of Borujen. Lower part of the Tarbur Formation, Upper Maastrichtian.

Diagnosis: Rather elongate subspecies of Frambocythere with the characteristic "raspberry-type" pustulose ornamentation. Postero-ventral conical spines only on juveniles and males. Left valve smaller than right valve (inverse overlap).

Dimensions: Holotype: L = 0.470 mm; h = 0.270 mm. Paratypes: L = 0.430-0.470 mm; h = 0.240-0.270 mm.

Description: Female carapace sub-rectangular with dorsal and ventral margins more or less parallel. Ventral margin slightly convex. Dorsal margin straight in anterior half, slightly convex in posterior half. Anterior margin equally rounded and compressed. Postero-dorsal margin angular with marked posterior cardinal angle in males. Postero-ventral margin rounded. Two sub-parallel vertical sulci running from dorsal margin downwards, one at mid-length, one shorter in anterior quarter. Surface of valves ornamented with

'raspberry-type' micropustules. Females have no or only one conical postero-ventral spine, whereas males and juveniles have at least

two spines (Pl. 1, fig. 2 ![]() ). Right valve overlaps left. Males slightly smaller and with much less inflated posterior region.

). Right valve overlaps left. Males slightly smaller and with much less inflated posterior region.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Plate 1: Frambocythere tumiensis zagrosensis

nov. subsp.

1. Carapace, female, holotype, right lateral view (L = 0.47 mm);

2. Carapace, male, paratype, left lateral view (L = 0.45 mm);

3. Carapace, female, dorsal view (L = 0.47 mm);

4. Carapace, female, ventral view (L = 0.46 mm).

Remarks: This subspecies differs from other subspecies of Frambocythere tumiensis by its more elongate carapace (females L/h = 1.7-1.80), for example, compared with Frambocythere tumiensis tumiensis (females L/h = 1.62-1.70) and Frambocythere tumiensis ferreri (females L/h = 1.64-1.77). It also differs from this last subspecies in that the surface of the valves is entirely pustulose and the postero-dorsal spine is absent. Two other subspecies described from the Upper Maastrichtian intertrappean beds of India, Frambocythere tumiensis anjarensis & , 1999, and Frambocythere tumiensis lakshmiae & , 2000, have more prominent papillae, as does the Early Paleocene subspecies from Belgium, Frambocythere tumiensis ludi , 1984.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Figure 2: View of the studied section, 48 km S of Borujen, Iran.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Figure 3: Schematic lithostratigraphic log of the Tarbur Formation.

The earliest known species of Frambocythere is of Gondwanian origin. It has been reported in the Albian (Loia Formation) of the Democratic Republic of Congo as Frambocythere pustulosa (, 1957) and also from the Albo-Aptian of Chad (, 1993; & , 1997).

Most other taxa of Frambocythere are subspecies of Frambocythere tumiensis (, 1978) from northern Spain and are of Late Maastrichtian age, but some subspecies extend into the Danian. Other species are known from the Upper Paleocene and the Lower Eocene as stated by (2011). From a palaeobiogeographic point of view, the distribution of the various subspecies of Frambocythere tumiensis during the Maastrichtian and earliest Danian is remarkable, as already stated by (1979). Frambocythere tumiensis tumiensis (, 1978), Frambocythere tumiensis aepleri (, 1978), and Frambocythere tumiensis ferreri , 1980, are present in southern Europe, i.e., north-eastern Spain and southern France , 1980; , 1991; et al., 1996), and one subspecies, Frambocythere tumiensis ludi , 1984, is known from the lowermost Paleocene (Danian) of southern Belgium.

In northwestern India, two species have been described from the Upper Maastrichtian and Lower Palaeocene: Frambocythere tumiensis anjarensis & , 1999, and Frambocythere tumiensis laskshamiae & , 2000 ( & , 1999; & , 2000, 2005, 2006; et al., 2002; et al., 2009). The same year as (1978) described the Spanish species as Bisulcocypris tumiensis, in north-west China, in H et al., 1978), named a species Bisulcocypris fanghiaensis from the Upper Maastrichtian. Better SEM illustrations in & (2002) clearly show (, 2011) that the Chinese species is a subspecies of Frambocythere tumiensis, herein named Frambocythere tumiensis fangjiahensis ( in H et al., 1978).

The presence of a new subspecies of Frambocythere tumiensis in the Maastrichtian of Iran is therefore a newly recognised link between southern Europe and the Far East (China). The extremely wide geographical distribution of this species is quite rare amongst fossil Cytherocopina since they very seldom have dessication-resistant eggs (, 2012). However, (1989) raised individuals belonging to the family Limnocytheridae from dried mud and & (2004) found a species of Paralimnocythere in a temporary pond confirming that limnocytherids have drought-resistant stages. There are also several living Cytherocopina that have very widespread distributions, e.g. Cytherissa lacustris (, 1863), Limnocythere inopinata (, 1843), Limnocythere stationis , 1891, Leucocythere mirabilis (, 1892), and Cyprideis torosa (, 1850). Therefore there may be a strong relationship between desiccation-resistant eggs and wide distributions (R.J. personal communication; et al. (2008) reported that 90% of freshwater ostracode species are restricted to one zoogeographical region. Half of these are Cypridoidea which have desiccation-resistant eggs. On the other hand, Darwinula stevensoni ( & , 1870), which does not have desiccation-resistant eggs, has a very wide geographical distribution. Birds are thought to be one of the most common means of passive dispersal (, 1964; , 1990), especially for ostracodes that do not lay desiccation-resistant eggs such as most Cytherocopina. Other passive dispersal vectors are amphibians (, 1989), fishes ( & , 1971), floating vegetation and stratospheric air currents ( & , 1979). Some Cytherocopina which do not lay desiccation-resistant eggs may disperse in a torpid (dehydrated) state (, 1993).

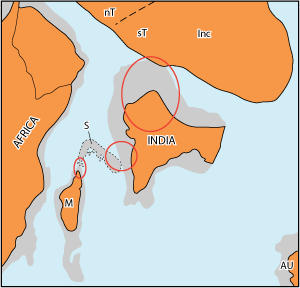

The presence of Frambocythere in the Maastrichtian of India is more difficult to explain since the collision of India with Asia is dated 10

Ma years later, at about 55 Ma ( et al.,

2007). The most likely scenario is that

Laurasian terrestrial taxa, including ostracodes, amphibians and vertebrates, entered India following a presumed terrestrial route as suggested by &

(1991), &

(2009) and (2003) (Fig. 4 ![]() ). This

postulate is not accepted by &

(2006) who, on the basis of freshwater ostracode faunas, support

the isolation of the Indian subcontinent during the Late Cretaceous and the "Out of India" hypothesis with respect to

India's zoogeograpical relations with Africa and Laurasia.

). This

postulate is not accepted by &

(2006) who, on the basis of freshwater ostracode faunas, support

the isolation of the Indian subcontinent during the Late Cretaceous and the "Out of India" hypothesis with respect to

India's zoogeograpical relations with Africa and Laurasia.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Figure 4: Palaeogeographic relationships of India during the Late Maastrichtian (after , 2003, modified). Orange: terrestrial areas; light grey; presumed terrestrial connections; M: Madagascar; S: Seychelles Plateau; nT: northern Tibet; sT: southern Tibet; Inc: Indochina.

We are indebted to the late Dr. E. (Commodoro Rivadavia, Argentina) for the identification of the charophytes, and the reviewers, M.C. (Lisboa, Portugal) and R.J. (Shiga, Japan), and the editors, M. (Nice, France) and S. (Ballarat, Australia), for their careful review and improvement of the text.

This paper was presented by the senior author in Tunis, on May 6th 2010, during the 23rd ROLF (Réunion des Ostracodologistes de Langue Française), and later in Paris, on August 30th, during the 4th "French" Congress on Stratigraphy (STRATI2010), respectively organized by Dr. R. and Prof. B. , who are warmly acknowledged.

J.C., J.R. & A.M. (2007).- When and where did India and Asia collide?- Journal of geophysical Research, Washington D.C., vol. 112, p. 1-19.

(2004).- Regional stratigraphy of the Zagros fold-thrust belt of Iran and its proforeland evolution.- American Journal of Science, New Haven, vol. 204, p. 1-20.

J.-F. (1980).- Les ostracodes du Crétacé supérieur de Provence. Systématique, biostratigraphie, paléoécologie, paléogéographie.- Travaux du Laboratoire de Géologie historique et Paléontologie de l'Université de Provence, Marseille, n° 10, 634 p.

J.-F., J.-P. & Y. (1996).- Late Cretaceous non-marine ostracods from Europe: biostratigraphy, palaeobiogeography and taxonomy.- Cretaceous Research, London, vol. 17, p. 151-167.

A. & J.-P. (1999).- Ostracodes limniques de sédiments inter-trappéens (Maastrichtien terminal-Paléocène basal de la région d'Anjar (Kachchh, Etat de Gujarat), Inde: systématique, paléoécologie et affinités paléobiogéographiques.- Revue de Micropaléontologie, Paris, vol. 43, n°1, p. 3-20.

J.-P. (1991).- On Frambocythere tumiensis () ferreri .- A Stereo-Atlas of Ostracod Shells, London, vol. 18, part 1, p. 37-40.

J.-P. (1993).- An early representative of the genus Frambocythere , 1980: Frambocythere pustulosa (, 1957) from the Albian of Zaire.- Journal of Micropalaeontology, London, vol. 12, n° 2, p. 170.

J.-P. (2011).- From light to darkness: from Frambocythere , 1980 to Kovalesvkiella , 1963 (Limnocytheridae, Timiriaseviinae).- Joannea Geologie und Paläontologie, Graz, Band 11, p. 44-47.

J.-P. & D.L. (1980).- Sur la morphologie, la systématique, la biogéographhie et l'évolution des ostracodes Timiriaseviinae (Limnocytheridae).- Paléobiologie continentale, Montpellier, vol. 11, n° 1, p. 1-52.

J.-P. & F. (1997).- Faunes d'ostracodes lacustres des bassins intra-cratoniques d'âge albo-aptien en Afrique de l'Ouest (Cameroun, Tchad) et au Brésil : considérations d'ordre paléoécologique et paléobiogéographique.- Africa Geoscience Review, Paris, vol. 4, n° 3-4, p. 431-450.

J.-P., H., A. & S. (2010).- Presence of the genus Frambocythere ,

1980, Ostracoda (Limnocytheridae, Timiriaseviinae) in the Upper Maastrichtian of the Zagros Mountains, Iran, a new relay between southern Europe and the Far East.- STRATI210, Paris, Abstract volume, p. 69-70.

Online at: http://www.univ-brest.fr/geosciences/conference/ocs/index.php/CFS/STRATI2010/paper/view/133

O., C. & Y. (1985).- Paléogène. In: H.J. (ed.), Atlas des ostracodes de France.- Bulletin des Centres de Recherche Exploration-Production Elf-Aquitaine, Mémoire 9, Pau, p. 257-311.

N. (1957).- Ostracodes du Bassin du Congo. I. Jurassique supérieur et Crétacé.- Annales du Musée Royal du Congo Belge, Tervueren, n° 19, p. 1-97.

E., V., A., S., C., de de F. & J. (1999).- Découverte de vertébrés dans les Calcaires de Rona (Thanétien ou Sparnacien), Transylvanie, Roumanie: les plus anciens mammifères cénozoïques d'Europe Orientale.- Geologicae Helvetiae Eclogae, Basel, vol. 92, n° 3, p. 517-535.

F.F. (1978).- Nichtmarine Ostrakoden aus der spanischen Oberkreide.- Berliner Geowissenchaften Abhandlungen, Berlin, Reihe A, n° 3, p. 71-78.

F.F. (1979).- Möglichkeiten der Verbreitung nichtmariner Ostrakodenpopulationen und dern Auswirkung auf die Phylogenie und die Stratigraphie.- Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Palöntologie Monatscheft, Stuttgart, Heft 6, p. 378-383.

D.J. (1993).- Survival strategy to escape dessication in a freshwater ostracod.- Crustaceana, Leiden, vol. 65, p. 53-61.

Youtang & Yunxian (2002).- Fossil Ostracoda of China (Vol. 1) - Superfamilies Cypridacea and Darwinulidacea.- China Scientific Books, Beijing, 1090 p. [in Chinese]

Youtang, Junde & Chunhui (1978).- The Cretaceous-Tertiary ostracods from the marginal region of the Yangtez-Han River Plain in Central Hubei.- Memoir of the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology, n° 9, p. 129-206 [in Chinese].

G.A. & J.G. (1965).- Stratigraphic nomenclature of Iranian oil consortium agreement area.- American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Bulletin, Tulsa, vol. 49, p. 2182-2245.

A. (1976).- Microbiostratigraphy of the Sarvestan area, Southwestern Iran.- National Iranian Oil Company, Tehran, n° 5, 130 p.

I. (2012).- Recent freshwater ostracods of the world.- Springer, Heidelberg, 608 p.

G., T., S., D.M., M., A., R., S.C., B., D. & i A. (2009).- K-T transition in Deccan Traps of central India marks major marine seaway across India.- Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Amsterdam, vol. 282, p. 10-23.

A.R., & Y M. (2010).- Maastrichtian rudist fauna from Tarbur Formation (Zagros Region, SW Iran): preliminary observations.- Turkish Journal of Earth Sciences, Ankara, vol. 19, p. 703-719.

L.S. & I.G. (1971).- Viability of ostracod eggs egested by fish and effect of digestive fluids on ostracod shell - ecologic and paleoecologic implications. In: H.J. (ed.), Paléoécologie des ostracodes.- Bulletin du Centre de Recherches Pau-SNPA, Pau, 5 suppl., p. 125-135.

K. (1989).- Ovambocythere milani gen. n., spec. n. (Crustacea, Ostracoda), an African limnocytherid reared from dried mud.- Journal of African Zoology, Matieland, n° 103, p. 379-388.

K., I., C. & D.J. (2008).- Global biodiversity of non-marine Ostracoda (Crustacea).- Hydrobiologia, Heidelberg, vol. 595, p. 185-193.

G.V.R. & J.C. (1991).- A discoglossid frog in the latest Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of India. Further evidence for a terrestrial route between India and Laurasia in the latest Cretaceous.- Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris, (II), n° 313, p. 272-278.

G.V.R. & A. (2009).- Late Cretaceous continental vertebrate fossil record from India: palaeobiogeographical insights.- Bulletin de la Société géologique de France, Paris, vol. 180, n° 4, p. 369-381.

V.W. (1964).- Viability of crustacean eggs recovered from ducks.- Ecology, Ithaca, vol. 45, n° 3, p. 656-658.

J.-C. (2003).- Relationships of the Malagasy fauna during the Late Cretaceous: northern or southern routes.- Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, Warsaw, vol. 48, n° 4, p. 661-662.

B. (1989).- Phoresis of Cyclocypris ovum () (Ostracoda, Podocopida, Cyprididae) on Bombina variegata () (Anura, Amphibia) and Triturus vulgaris () (Urodela, Amphibia).- Crustaceana, Leiden, vol. 57, n° 2, p. 171-176.

R.J. & D.J. (2004).- The first British record of Paralimnocythere psammophila (, 1965) (Ostracoda, Cytheroidea, Limnocytheridae).- Journal of Micropalaeontology, London, vol. 23, part 2, p. 133-134.

I.G. & L.S. (1979).- Viability of freeze-dried eggs of the freshwater Heterocypris incongruens. In: N. (ed.), Taxonomy, biostratigraphy and distribution of ostracodes.- Serbian Geological Society, Belgrade, p. 1-5.

T. (1990).- The dispersal ability of Cytherissa lacustris. In: D.L., P. & J.-P. (eds.), Cytherissa (Ostracoda), the Drosophila of paleolimnology.- Bulletin de l'Institut de Géologie du Bassin d'Aquitaine, Talence, n° 47-48, p. 135-138.

Y. (1984).- Les ostracodes du "Montien Continental" de Hainin, Hainault, Belgique.- Revue de Micropaléontologie, Paris, vol. 27, n° 2, p. 144-156.

Y., C., M. & J. (1991).- Flores et faunes continentales ilerdiennes du versant sud de la Montagne Noire et de la Montagne d'Alaric.- Revue de Micropaléontologie, Paris, vol. 34, n° 1, p. 69-89.

H., A., S., A. & A.R. (2010).- Introducing the clastic-carbonate and red clastic sediments of Maastrichtian in High Zagros region (Semiron-Ardal).- Journal of Science University of Teheran, Teheran, vol. 36, n° 1, p. 103-117.

H., A. & A. (2005).- Microfacies, paleoenvironments and sequence stratigraphy of the Tarbur Formation in Kherameh area, SW Iran.- Carbonates and Evaporites, New York, vol. 20, n° 2, p. 131-137

R.C. & S. (2000).- A new fauna of Late Cretaceous non-marine Ostracoda from the Deccan intertrappean beds of Lakshmipur, Kachchh (Kutch) District, Gujarat, and Western India.- Revista Española de Micropaleontologia, Madrid, vol. 32, n° 3, p. 385-409.

R.C. & S. (2005).- Some aspects of the paleoecology and distribution of non-marine Ostracoda from Upper Cretaceous intertrappean deposits and the Lameta Formation of peninsular India.- Journal of the Palaeontological Society of India, Lucknow, vol. 50, n° 2, p. 61-76.

R.C. & S. (2006).- Extensive endemism among the Maastrichtian non-marine Ostracoda of India with implications for palaeobiogeography and "out of India" dispersal.- Revista Española de Micropaleontologia, Madrid, vol. 38, n° 2-3, p. 229-244.

R.C., S. & S. (2002).- Upper Cretaceous non-marine Ostracoda from intertrappean horizons in Gulbarga District, Karnataka State, South India.- Revista Española de Micropaleontologia, Madrid, vol. 34, n° 2, p. 163-186.