◄ Carnets Geol. 24 (1) ►

Outline:

[1. Introduction] [2.

Geographical and geological context of the Melilla-Nador basin]

[3. Material and methods]

[4. Biostratigraphic results (Foraminifera)]

[5. Palynological results]

[6. Discussion] [7. Conclusions] [Bibliographic references] and ... [Plates]

Hassan II University of Casablanca, Faculty of Sciences Ben M'sik, Geology Department, Geosciences and Applications Laboratory, B.P 7955, Sidi Othmane Casablanca

(Morocco)

Hassan II University of Casablanca, Faculty of Sciences Ben M'sik, Geology Department, Geosciences and Applications Laboratory, B.P 7955, Sidi Othmane Casablanca

(Morocco)

Hassan II University of Casablanca, Faculty of Sciences Ben M'sik, Geology Department, Geosciences and Applications Laboratory, B.P 7955, Sidi Othmane Casablanca (Morocco)

Hassan II University of Casablanca, Faculty of Sciences Ben M'sik, Geology Department, Geosciences and Applications Laboratory, B.P 7955, Sidi Othmane Casablanca (Morocco)

Hassan II University of Casablanca, Faculty of Sciences Ben M'sik, Geology Department, Geosciences and Applications Laboratory, B.P 7955, Sidi Othmane Casablanca (Morocco)

Hassan II University of Casablanca, Faculty of Sciences Ben M'sik, Geology Department, Geosciences and Applications Laboratory, B.P 7955, Sidi Othmane Casablanca (Morocco)

Sorbonne Université, CNRS-INSU, Institut des Sciences de la Terre Paris, ISTeP UMR 7193, 75005 Paris (France)

Geobiostratdata.consulting, 385 Rte du Mas Rillier, 69140 Rillieux-la-Pape (France)

Published online in final form (pdf) on January 17, 2024

DOI:

10.2110/carnets.2024.2401

![]()

[Editor: Bruno

R.C. Granier; language editor: Stephen Eagar]

In order to contribute to the understanding of the evolution of marine and continental

environments, preceding the onset of the Messinian salinity crisis in the western

Mediterranean, we conducted an integrated study of the pre-evaporitic Messinian sedimentary series in the Melilla-Nador basin. Three sections have been carried out in the marl-diatomite series and were the subject of a detailed biostratigraphic and palynological

study. The study of planktonic foraminifera, pollen, dinocysts, and palynofacies allowed us to characterize the evolution of these

environments. From 6.83 to 6.52 Ma, the marine environment was relatively open,

calm, probably subject to the action of upwellings and received periodic continental inputs. Starting 6.52 Ma, the abundance and diversity of planktonic foraminifera

decreased. Continental inputs gradually dominate, alternating with marine ones, and reflecting a succession between proximal and distal neritic

environments. The surface water conditions were warm. After 6.35 Ma, began the degradation of marine conditions. The continental environment shows an open vegetal landscape dominated by herbaceous plants, reflecting a tropical to arid subtropical

climate, slightly less dry than that of the South Rifian Corridor.

This study confirms the existence of several parameters that contributed to the deposition of the cyclical marl-diatomite

series: on the one hand, the hot and dry climate favored the reduction of the plant landscape and therefore erosion (continental inputs); on the

other, the tectonics (volcanism and uplift).

• Melilla-Nador basin;

• Morocco;

• Western

Mediterranean;

• pre-evaporitic Messinian;

• marine environment;

•

continental environment;

• Foraminifera;

• pollen;

• dinocysts

Bahaj H., Barhoun N., Bachiri Taoufiq N., Rahmouna J., Targhi S., Berry N., Suc J.-P. & Popescu S.-M. (2024).- Paleoenvironmental changes preceding the onset of the Messinian salinity crisis in the western Mediterranean Sea (pre-evaporitic Messinian of the Melilla-Nador Basin, NE Morocco).- Carnets Geol., Madrid, vol. 24, no. 1, p. 1-27. DOI: 10.2110/carnets.2024.2401

Changements paléoenvironnementaux précédant le

début de la crise de salinité du Messinien dans la mer Méditerranée

occidentale (Messinien préévaporitique du bassin de Melilla-Nador, Maroc NE).-

Afin de contribuer à la compréhension de l'évolution des environnements marins et continentaux, précédant le début de la crise de salinité messinienne dans la Méditerranée occidentale, nous avons mené une étude intégrée de la série sédimentaire messinienne préévaporitique dans le bassin de Melilla-Nador. Trois coupes ont été réalisées dans la série marno-diatomique et ont fait l'objet d'une étude biostratigraphique et palynologique détaillée. L'étude des foraminifères planctoniques, du pollen, des dinokystes et du palynofaciès a permis de caractériser l'évolution de ces environnements. De 6,83 à 6,52 Ma, le milieu marin est relativement ouvert, calme, probablement soumis à l'action des upwellings et reçoit périodiquement des apports continentaux. À partir de 6,52 Ma, l'abondance et la diversité des foraminifères planctoniques diminuent. Les apports continentaux, alternant avec des apports marins, deviennent progressivement dominants, l'ensemble reflétant une succession cyclique entre des environnements néritiques proximal et distal. Les conditions de l'eau de surface sont chaudes. Après 6,35 Ma, commence la dégradation des conditions marines. L'environnement continental montre un paysage végétal ouvert dominé par des plantes herbacées, reflétant un climat tropical à subtropical aride, légèrement moins sec que celui du Corridor Sud

Rifain.

Cette étude confirme l'existence de plusieurs paramètres qui ont contribué au dépôt de la série cyclique marno-diatomitique avec, d'une part, le climat chaud et sec favorisant l'ouverture du paysage végétal et donc l'érosion (apports continentaux) et, d'autre part, la tectonique (volcanisme et soulèvement).

• bassin de Melilla-Nador ;

• Maroc ;

•

Méditerranée occidentale ;

• Messinien préévaporitique ;

• environnement marin ;

•

environnement continental ;

• foraminifères ;

• pollen ;

•

dinokystes

The Messinian salinity crisis -MSC- (Hsü et al., 1973, 1977) stands as an exceptional event that profoundly influenced the recent history of the Mediterranean basin. It resulted from the successive closure of the Betic and Rifian corridors (Krijgsman et al., 1999a, 1999b; Martín et al., 2001; Rouchy et al., 2003; Warny et al., 2003; CIESM, 2008; Bache et al., 2015; Gorini et al., 2015a, 2015b; Flecker et al., 2015; Tulbure et al., 2017; Capella et al., 2018, 2019; Targhi et al., 2021), which previously served as gateways for water exchange between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea during the Late Miocene (Flecker et al., 2015; Achalhi et al., 2016; Capella et al., 2018, 2019; Krijgsman et al., 2018; Suc et al., 2019).

The progressive isolation of the Mediterranean has caused an important environmental change that has had an impact on the terrestrial and marine ecosystems of the Mediterranean region (Saint-Martin et al., 2003; Vasiliev et al., 2013, 2019; Roveri et al., 2014; Flecker et al., 2015; Agiadi et al., 2017; Karakitsios et al., 2017a, 2017b; Moissette et al., 2018; Suc & Frizon de Lamotte, 2019; Kontakiotis et al., 2019, 2020). The pre-evaporitic Messinian series of the peripheral Mediterranean basins are characterized by a typical succession of clays/marls surmounted by a cyclic series of marls and diatomites or sapropels (Sierro et al., 1993, 1999; Saint-Martin et al., 2003; Assen et al., 2006; Achalhi et al., 2016). These sediments have registered the changes that preceded the Messinian salinity crisis.

The Melilla-Nador peripheral basin, located in the northeast of Morocco, represents the eastern segment of the southern Rifian corridor. The sedimentary sequence of this basin consists of an Upper Miocene carbonate platform exhibiting reef characteristics, laterally passing to clays and marl-diatomite alternations (Saint-Martin & Rouchy, 1990; Cornée et al., 1996; Saint-Martin et al., 2003).

Extensive research has focused on the Messinian sedimentation in this basin, encompassing stratigraphical, paleontological, and sedimentological investigations (Guillemin et Houzay, 1982; Rouchy, 1982; Saint-Martin & Rouchy, 1986; Saint-Martin, 1990; Saint-Martin et al., 1991; Gaudant et al., 1994; Cunningham et al., 1994; Saint-Martin & Cornée, 1996; Cornée et al., 1996, 2002, 2006; Rachid et al., 1997; Münch et al., 2001). However, the vegetation and, consequently, the climatic context in the Melilla-Nador basin before the Messinian salinity crisis remains poorly known. The present work is based on the detailed analyses of planktonic foraminifera, spores, pollen, dinocysts, and palynofacies from three selected sections in the study basin. The primary objectives of this study are, on one hand, to provide a better knowledge of the evolution of the marine environments and, on the other hand, to address the information gap regarding the continental environments by reconstructing the vegetation and climate of this basin during the pre-evaporitic Messinian.

Building upon a recently developed high-resolution biostratigraphic analysis for the Mediterranean (Sierro et al., 1993, 2001; Lourens et al., 2004; Assen et al., 2006; Corbí & Soria, 2016; Karakitsios et al., 2017a, 2017b; Kontakiotis et al., 2019; Lirer et al., 2019), a precise biostratigraphic framework has been established for the studied sediments. The study represents a new contribution to the reconstruction of the paleoclimates and the evolution of marine and continental environments during the pre-evaporitic Messinian in the Melilla-Nador basin, within a well-defined chronostratigraphic context. The aim is to enhance our understanding of the impact of the narrowing of the southern Rifian corridor on the climate and environment during a critical period in the history of the Mediterranean.

The Melilla-Nador basin, situated in the northeastern Rif near the Cap des Trois-Fourches

(Fig. 1

![]() ), is bordered to the south by the metamorphic terrains of the Rif

foreland. Neogene sediments were deposited unconformably on metamorphic rocks or tectonized Tortonian formations (Guillemin & Houzay,

1982). South of the Trois-Fourches cape, this basin is characterized by the development of a carbonate reef platform passing laterally into a basal marl-diatomite

sequence, which includes cinerite intercalations (Saint-Martin & Cornée,

1996; Münch et al.,

2001; Saint-Martin et al.,

2003; Assen et al.,

2006; Münch et al., 2006; Cornée et al.,

2006). The cyclical succession of marl and diatomite was deposited in shallow marine conditions registering precession cycles (Assen et al.,

2006). The carbonate platform is initially characterized by conglomeratic to bioclastic retrogradational

deposits, followed by bioclastic and reef carbonate prograding deposits (Saint-Martin & Cornée,

1996; Saint-Martin et al.,

2003; Cornée et al.,

2006). The initiation of cyclic sedimentation in the Melilla-Nador basin commenced around 6.84 Ma, marking a restriction of paleo-circulation across the basin and the onset of bioclastic platform progradation along the

shoreline. The restriction of paleo-circulation is linked to the reduction of the southern Rif corridor (Assen et al.,

2006). The commencement of diatomite deposition in the Melilla Basin aligned with the tectonic subsidence of the Taza-Guercif Basin and potentially with the initiation of siphoning of intermediate Atlantic waters through the narrowing Rifian corridor (Assen et al.,

2006). A change in diatom species from boreal to tropical coincided with the appearance of prograding coral reefs along the shelf (Assen et al.,

2006). This event indicates a decline in the inflow of cold water from the Atlantic

(ending the siphoning, according to Benson et al.,

1991). The end of diatomite deposition marks the closure of the open marine environment of the Melilla Basin (Assen et al.,

2006; Flecker et al., 2015).

), is bordered to the south by the metamorphic terrains of the Rif

foreland. Neogene sediments were deposited unconformably on metamorphic rocks or tectonized Tortonian formations (Guillemin & Houzay,

1982). South of the Trois-Fourches cape, this basin is characterized by the development of a carbonate reef platform passing laterally into a basal marl-diatomite

sequence, which includes cinerite intercalations (Saint-Martin & Cornée,

1996; Münch et al.,

2001; Saint-Martin et al.,

2003; Assen et al.,

2006; Münch et al., 2006; Cornée et al.,

2006). The cyclical succession of marl and diatomite was deposited in shallow marine conditions registering precession cycles (Assen et al.,

2006). The carbonate platform is initially characterized by conglomeratic to bioclastic retrogradational

deposits, followed by bioclastic and reef carbonate prograding deposits (Saint-Martin & Cornée,

1996; Saint-Martin et al.,

2003; Cornée et al.,

2006). The initiation of cyclic sedimentation in the Melilla-Nador basin commenced around 6.84 Ma, marking a restriction of paleo-circulation across the basin and the onset of bioclastic platform progradation along the

shoreline. The restriction of paleo-circulation is linked to the reduction of the southern Rif corridor (Assen et al.,

2006). The commencement of diatomite deposition in the Melilla Basin aligned with the tectonic subsidence of the Taza-Guercif Basin and potentially with the initiation of siphoning of intermediate Atlantic waters through the narrowing Rifian corridor (Assen et al.,

2006). A change in diatom species from boreal to tropical coincided with the appearance of prograding coral reefs along the shelf (Assen et al.,

2006). This event indicates a decline in the inflow of cold water from the Atlantic

(ending the siphoning, according to Benson et al.,

1991). The end of diatomite deposition marks the closure of the open marine environment of the Melilla Basin (Assen et al.,

2006; Flecker et al., 2015).

Bioclastic limestones and prograding Porites fringing reefs characterize the Messinian transgressive system of the studied basin. These sediments transition basinwards to open marine marl, diatomite, and volcano-clastic deposits (Cornée et al., 2006). The age of prograding carbonate deposits varies, ranging from around 6.87±0.02 Ma (Roger et al., 2000) to 5.95-5.99 Ma (Cornée et al., 2006). The conclusion of this transgressive cycle (Cycle 1) is marked by the development of Halimeda algal beds around 6.08 Ma. This Halimeda-rich level serves as a reference point across the entire basin.

The second carbonate complex, known as the Terminal Carbonate Complex (TCC) or Cycle 2, is of Messinian age. It exhibits a flat aggrading-retrograding geometry (Cornée et al., 2002, 2006; Münch et al., 2006) and comprises reefs, giant microbial accumulations, and a combination of siliciclastic-oolitic coastal deposits associated with stromatolites. Two major unconformities border this complex (Münch et al., 2006). The 40Ar/39Ar dating places the base of the TCC (Terminal Carbonate Complex), coinciding with the onset of the Messinian salinity crisis (Münch et al., 2006), at an average of 5.95 to 5.99 Ma. Previous interpretations suggested that Cycle 2 deposits could be partially identified as continental Lago Mare-type deposits (Rouchy et al., 2003). However, taking into account that the Melilla-Nador basin emerged after the deposition of Upper Messinian sediments from marine Cycle 2 (Cornée et al., 2006), Münch et al. (2006) demonstrated that these continental deposits evolved laterally into marine deposits, emphasizing the link between the emersion of the Melilla platform and tectono-magmatic activity.

The second major unconformity, corresponding to the major surface of the Upper Messinian, caps the CCT deposits in the Melilla basin. This erosion surface is associated to the primary Messinian drawdown in the Mediterranean. The duration of the hiatus does not exceed 450 kyr (Münch et al., 2006). The TCC can be considered as the marginal equivalent of the Messinian Salinity Crisis evaporites (Assen et al., 2006). Re-flooding deposits (Cycle 3) have primarily developed only in the southwestern part of the basin (Cornée et al., 2006). They consist of yellowish marine sandstones and Isognomon limestones lying on the Messinian erosional surface. They constitute the second index level in the series. The sediments of Cycle 3 have been attributed to the Pliocene (Choubert et al., 1966; Guillemin & Houzay, 1982; Münch et al., 2001, 2006; Cornée et al., 2002, 2006).

|

Figure 1: Simplified geological map of the Melilla-Nador basin (Choubert et al.,

1966) and the location of the studied

sections. |

The material studied is derived from three strategically located sections in the Melilla-Nador basin, namely the

Messadit, Izarorène, and Ifounassene sections

(Fig. 1

![]() ). These sections were meticulously sampled, resulting in the collection of more than 139 samples. However, only 103 samples exhibiting well-preserved microfauna and suitable for micropaleontological and biostratigraphical study are represented on the stratigraphic columns

(Figs. 2

). These sections were meticulously sampled, resulting in the collection of more than 139 samples. However, only 103 samples exhibiting well-preserved microfauna and suitable for micropaleontological and biostratigraphical study are represented on the stratigraphic columns

(Figs. 2

![]() -

3

-

3

![]() -

4

-

4

![]() ). The sampling interval ranges between 0.5 and 1.5 m.

We aimed for dense sampling to effectively capture variations in microfaunal associations and to account for lithological changes.

). The sampling interval ranges between 0.5 and 1.5 m.

We aimed for dense sampling to effectively capture variations in microfaunal associations and to account for lithological changes.

The Messadit section is situated in the western part of the peninsula, in the south of the village of Messadit

(Fig. 1

![]() ). The section has a thickness of 70 m and is characterized by marl-diatomite alternations containing several cinerite levels. This section is the most comprehensive, encompassing the key events of the Late Messinian in Morocco (Gaudant et al.,

1994; Saint-Martin & Cornée,

1996; Rachid et al.,

1997; Saint-Martin et al.,

2003; Assen et al.,

2006)

(Fig. 2

). The section has a thickness of 70 m and is characterized by marl-diatomite alternations containing several cinerite levels. This section is the most comprehensive, encompassing the key events of the Late Messinian in Morocco (Gaudant et al.,

1994; Saint-Martin & Cornée,

1996; Rachid et al.,

1997; Saint-Martin et al.,

2003; Assen et al.,

2006)

(Fig. 2

![]() ). At the base of the section, there is a volcano-sedimentary level that unconformably lies on glauconitic sands. Some authors (Gaudant et al.,

1994; Rachid et al., 1997) have described this level as a glauconitic conglomerate level with Messinian age overlying sedimentary Tortonian

units. The marl/diatomite alternations contain both planktonic and benthic foraminifera, ostracods, bivalves, bryozoans, sponge spicules, diatoms, and fish remains (Gaudant et al.,

1994; Rachid et al., 1997; Saint-Martin et al.,

2003). Indurated silicified laminites are intercalated in some places within this sedimentary series. Toward the upper part of the section, two oyster beds (Pycnodonte) were

observed. Assen et al. (2006) conducted a cyclostratigraphic study revealing 35 sedimentary cycles well calibrated on the astronomical time scale. Some cinerite layers have been dated using the isotope method (Roger et al.,

2000; Assen et al., 2006), providing precise dating for the carbonate sequences of the Melilla-Nador basin. Halimeda algae limestone banks, which represents the lateral equivalent of the last prograding coral reefs (Roger et al.,

2000; Saint-Martin et al., 2003; Cornée et al.,

2006), cap the

section. A total of thirty-six samples

(Fig. 2

). At the base of the section, there is a volcano-sedimentary level that unconformably lies on glauconitic sands. Some authors (Gaudant et al.,

1994; Rachid et al., 1997) have described this level as a glauconitic conglomerate level with Messinian age overlying sedimentary Tortonian

units. The marl/diatomite alternations contain both planktonic and benthic foraminifera, ostracods, bivalves, bryozoans, sponge spicules, diatoms, and fish remains (Gaudant et al.,

1994; Rachid et al., 1997; Saint-Martin et al.,

2003). Indurated silicified laminites are intercalated in some places within this sedimentary series. Toward the upper part of the section, two oyster beds (Pycnodonte) were

observed. Assen et al. (2006) conducted a cyclostratigraphic study revealing 35 sedimentary cycles well calibrated on the astronomical time scale. Some cinerite layers have been dated using the isotope method (Roger et al.,

2000; Assen et al., 2006), providing precise dating for the carbonate sequences of the Melilla-Nador basin. Halimeda algae limestone banks, which represents the lateral equivalent of the last prograding coral reefs (Roger et al.,

2000; Saint-Martin et al., 2003; Cornée et al.,

2006), cap the

section. A total of thirty-six samples

(Fig. 2

![]() ) were

palynogically and biostratigraphically analyzed with planktonic foraminifera.

) were

palynogically and biostratigraphically analyzed with planktonic foraminifera.

The Ifounassene section is situated in the eastern part of the peninsula

(Fig. 1

![]() ) and corresponds to the lower part of the Rostrogordo section (Saint-Martin & Rouchy,

1986; Cunningham et al.,

1994; Gaudant et al., 1994; Rachid et al.,

1997). The visible Messinian series is characterized by marl-diatomite alternations incorporating volcano-sedimentary

(cinerites) and bioclastic levels

(Fig. 2

) and corresponds to the lower part of the Rostrogordo section (Saint-Martin & Rouchy,

1986; Cunningham et al.,

1994; Gaudant et al., 1994; Rachid et al.,

1997). The visible Messinian series is characterized by marl-diatomite alternations incorporating volcano-sedimentary

(cinerites) and bioclastic levels

(Fig. 2

![]() ). The section is 30 m thick and overlaid by Halimeda limestone, representing the lateral equivalent of the prograding coral constructions of Unit 3 (Roger et al.,

2000; Saint-Martin et al., 2003; Cornée et al.,

2006; Cunningham et al.,

1994). The section commences with homogeneous gray marls containing a Neopycnodont (Neopycnodonte navicularis) accumulation level (Rachid et al.,

1997) and resting on a volcano-sedimentary base

level. Assen et al. (2006) identified seventeen sedimentary cycles in this section, comprising alternating diatomite levels and homogeneous, partly silty marls containing bryozoans, bivalves, and

echinoderms. Benthic foraminifera, planktonic foraminifera, and ostracods constitute the primary microfauna in the sediments. The upper part of the section is composed of homogeneous sandy marls and two silicified and laminated levels with fish remains (Gaudant et al.,

1994). Twenty-five samples

(Fig. 2

). The section is 30 m thick and overlaid by Halimeda limestone, representing the lateral equivalent of the prograding coral constructions of Unit 3 (Roger et al.,

2000; Saint-Martin et al., 2003; Cornée et al.,

2006; Cunningham et al.,

1994). The section commences with homogeneous gray marls containing a Neopycnodont (Neopycnodonte navicularis) accumulation level (Rachid et al.,

1997) and resting on a volcano-sedimentary base

level. Assen et al. (2006) identified seventeen sedimentary cycles in this section, comprising alternating diatomite levels and homogeneous, partly silty marls containing bryozoans, bivalves, and

echinoderms. Benthic foraminifera, planktonic foraminifera, and ostracods constitute the primary microfauna in the sediments. The upper part of the section is composed of homogeneous sandy marls and two silicified and laminated levels with fish remains (Gaudant et al.,

1994). Twenty-five samples

(Fig. 2

![]() ) were analyzed

palynogically and biostratigraphically (with planktonic foraminifera).

) were analyzed

palynogically and biostratigraphically (with planktonic foraminifera).

|

Figure 2:

Lithostratigraphy of the studied sections (MES : Messadit section, IZA : Izarorène section, IFO : Ifounassene section). |

It is located in the east of the village of Izarorène, about 5 km to the ESE of the confluence of the oued Kert with the Mediterranean

(Fig. 1

![]() ). This is a thick series of marls where laminated diatomite levels are intercalated in the upper part of the section (Barhoun et al.,

1999). The section begins with homogeneous blue to gray clayey marl, poorly stratified, overlying a level of white cinerite

(Fig. 2

). This is a thick series of marls where laminated diatomite levels are intercalated in the upper part of the section (Barhoun et al.,

1999). The section begins with homogeneous blue to gray clayey marl, poorly stratified, overlying a level of white cinerite

(Fig. 2

![]() ). In this section, Assen et al.

(2006) identified six cycles consisting of alternating diatomites and homogeneous marls. Above the third diatomite level, two cinerite levels are intercalated in the homogeneous marls. The section was densely sampled from the top of the first diatomite level. Forty-two samples

(Fig. 2

). In this section, Assen et al.

(2006) identified six cycles consisting of alternating diatomites and homogeneous marls. Above the third diatomite level, two cinerite levels are intercalated in the homogeneous marls. The section was densely sampled from the top of the first diatomite level. Forty-two samples

(Fig. 2

![]() ) were analyzed

palynogically and biostratigraphically (with planktonic foraminifera).

) were analyzed

palynogically and biostratigraphically (with planktonic foraminifera).

The samples underwent washing and sieving using the standard method (Barhoun, 2000). Qualitative and quantitative analyses of planktonic foraminiferal associations were conducted on residues containing a minimum of 300 individuals of the 150 µm fraction. To gain insights into paleoenvironments, two ecological indices were calculated:

1) the Planktonic-Benthic Ratio (P/P+B). This ratio, expressed as P/(P+B) x 100 (the percentage of planktonic foraminifera to the total foraminifera population), is commonly used to reconstruct paleobathymetry (Gibson, 1989). It also provides information about upwelling phenomena that favor high productivity (Mathieu, 1986, 1988; Bellier et al., 2010);

2) the Diversity Index. The species diversity in planktonic foraminiferal assemblages is based on the Shannon-Weaver function (Shannon & Weaver, 1949). It is calculated from the number of individuals of each species and the number of species for each sample. The estimation of the diversity index considers the proportion of each species in the total population. The Shannon index considers both the abundance and the uniformity of the species present (Daget, 1979; Murray, 1991).

Isc = - ∑ ( qi / Q x Ln qi / Q)

qi = the number of individuals counted for each species

Q = the total number of individuals for each level

The distribution of planktonic foraminifera is presented in tables. The number of specimens corresponding to abundant, common, and present is: Abundant > 20%; Common = 5-20%, and Present = 1-5%.

The standard palynological method, commonly employed for sediment treatment, was utilized for sample preparation following the procedure outlined by Bachiri Taoufiq

(2000). It involved HCl and HF treatments, followed by sieving of the residues between 10 and 180 µm, and an organic matter enrichment procedure using ZnCl2. Samples from Izarorène and Messadit sections

are poor in pollen and

dinocysts. Only 13 samples from the Ifounassene section yielded sufficient pollen grains and dinocysts (at least 160 pollen grains without Pinaceae and 100 dinocysts were counted). Based on the ecology of their representatives, the pollen taxa were grouped in a synthetic diagram (Suc et al.,

2018;

Fig. 7

![]() ), with the frequencies of each taxon represented in a detailed

diagram.

), with the frequencies of each taxon represented in a detailed

diagram.

To deduce global climate parameters, several methods were applied. The mean annual temperature (Tann) was estimated using current ecological conditions for plant groupings (Nix, 1982): megathermal elements (24°C), megamesothermal elements (20-24°C), mesothermal elements (14-24°C), and microthermal elements (10-14°C). For humidity assessment, the ratio Poaceae/Asteraceae (Cour & Duzer, 1978) was used. According to Cour and Duzer (1978), a Poaceae/Asteraceae ratio > 20 indicates a relatively humid climate, with precipitation exceeding 500 mm/year; conversely, a Poaceae/Asteraceae ratio < 20 indicates an arid climate with annual precipitation not exceeding 500 mm/year. Dry conditions favor the development of Asteraceae, whereas wet conditions favor Poaceae.

To reconstruct the marine environment, we applied indices previously used in the Neogene of Morocco by Warny (1999), Bachiri Taoufiq (2000), and Targhi et al. (2021, 2023). These indices are derived from the environmental preferences of dinocysts as recognized in the literature (Vernal et al., 1994, 1998, 2001; Vernal & Marret, 2007; Marret et al., 2001; Zonneveld, 1995, 1996; Zonneveld et al., 2013; Londeix et al., 2007). The curve resulting from the D/S ratio (D: Dinocysts and S: Spores + Pollen) is used to appreciate the marine influence versus the continental influence (Morzadec-Kerfourn, 1976; Tyson, 1993; Warny, 1999). The curve resulting from the G/P ratio (Tyson, 1993; Warny, 1999) is used to detect the inshore-offshore direction (G: Gonyaulacoid family, P: Peridinoid family). The IN/ON distality index is the ratio of inner platform neritic assemblages to outer platform neritic assemblages (Versteegh, 1994; Warny, 1999). The temperature index of surface waters is evaluated by the ratio of warm surface water dinocysts (W) to cool surface water dinocysts (C) (Warny, 1999). For the analysis of palynofacies, four standard groups have been identified in this work (Poumot & Suc, 1994; Combaz, 1991): woody organic matter (WOM), cellular organic matter (COM), black organic matter (BOM), and amorphous organic matter (AOM).

In light of recent work carried out on the Upper Neogene in the Mediterranean (Corbí & Soria, 2016; Karakitsios et al., 2017a, 2017b; Kontakiotis et al., 2019; Lirer et al., 2019), we conducted a detailed analysis of planktonic foraminiferal associations to revise the biostratigraphic framework of the studied sections. Three carefully chosen sections in the Melilla-Nador basin, where the Messinian deposits are thick and well represented, have been investigated (Messadit, Ifounassene, and Izarorène sections). Each section underwent intensive sampling to identify all the biostratigraphic and paleoenvironmental events characteristic of the Messinian. The analysis and detailed study of 103 samples collected from the three sections allowed the identification of 28 species of planktonic foraminifera, classified into 12 genera. To highlight biostratigraphic events, a complete count was performed on a portion containing about 300 individuals from the 150 μm fraction. In this work, we adopted high-resolution biostratigraphy, astronomically calibrated, recently utilized in the Mediterranean area, favoring precise dating and correlation (Hilgen et al., 1995; Krijgsman et al., 1994, 1995, 1999a, 1999b; Sierro et al., 1993, 2001; Lourens et al., 2004; Corbí et Soria, 2016; Karakitsios et al., 2017a, 2017b; Kontakiotis et al., 2019; Lirer et al., 2019). The main biostratigraphic events characterizing the Messinian in the Mediterranean area are indicated in Table 1.

Table 1: Main bioevents of planktonic foraminifera characterizing the Messinian in the Mediterranean area.

|

Planktonic foraminifera bioevents |

Chronostratigraphy (Ma) |

References |

|

Last Influx Turborotalita multiloba |

6.07 |

Sierro et al. (2001); Blanc-Valleron et al. (2002); Lourens et al. (2004) |

|

II Influx sinistral Neogloboquadrina acostaensis (40%) |

6.08 |

|

|

I Influx sinistral Neogloboquadrina acostaensis (90%) |

6.12 |

|

|

II Influx Turborotalita multiloba |

6.23 |

|

|

Influx dextral Globorotalia scitula |

6.29 |

|

|

S/D Neogloboquadrina acostaensis |

6.35-6.37 |

Sierro et al. (2001); Lourens et al.

(2004); |

|

FCO Turborotalita multiloba |

6.42 |

|

|

LO Globorotalia miotumida gr. |

6.52 |

|

|

LO Globorotalia nicolae |

6.72 |

Sierro et al. (2001); Blanc-Valleron et al.

(2002); |

|

FO Globorotalia nicolae |

6.83 |

|

|

Top dominant sinistral (Globorotalia) scitula gr. |

7.08 |

Lourens et al. (2004) |

|

influx conical Globorotalia miotumida |

7.18-7.22 |

Lourens et al. (2004) |

|

LCO Globorotalia menardii |

7.23 |

Hilgen et al. (2000a,

2000b); Lourens et al. |

|

FCO Globorotalia miotumida gr. |

7.24 |

Hilgen et al. (2000a,

2000b); Lourens et al. |

The micropaleontological study of sediments from the Messadit section reveals a remarkable richness in species and individuals of planktonic foraminifera, mainly in its lower part

(Table 2). The abundance of planktonic assemblages diminishes from moderate to low towards the upper part of the section. This study identified 28 species and 10 genera. The microfauna also includes benthic foraminifera, some ostracods, fragments of bivalve shells, sponge spicules, and urchin

radioles. In the marl and marl-diatomite levels, the planktonic microfauna is well-preserved, enabling a qualitative and quantitative biostratigraphic study, whereas planktonic foraminifera are deformed and poorly preserved in some diatomite levels, making their identification

challenging. The evolution of planktonic foraminiferal associations, diversity, and the plankton-benthic ratio in the Messadit section allow us to distinguish two intervals

(Fig. 3

![]() ):

):

The lower part of the section from MES 1 to MES 18 is characterized by high diversity with a Shannon Diversity Index between 1.9 and 2.28. The Planktonic/Benthic ratio varies between 60 and 90%. Planktonic foraminifera assemblages are dominated by globular forms such as Globigerinoides, Globigerina, Globoturborotalita, Neogloboquadrina, etc., compared to the keeled forms of Globorotalia, represented by Globor. miotumida and Globor. conomiozea. These deposits are characterized by a notable abundance of Globigerina bulloides and Globig. falconensis in some levels (MES 2-MES 6 and MES 9-MES 15).

The upper part of the section from MES 19 to MES 36: The microfauna in these sediments is characterized by average diversity, with a Shannon Diversity Index between 1.5 and 1.9. The Planktonic/Benthic ratio is average to low, fluctuating between 10 and 60%. Benthic foraminifera are globally abundant and well represented compared to planktonic foraminifera.

Table 2: Distribution of the main planktonic foraminifera species in Messadit section.

|

Figure 3:

Planktonic/Benthic ratio and Diversity Index of the studied sections. |

Biostratigraphic analysis and dating: The stratigraphic distribution and quantitative analysis of planktonic foraminifera species, especially markers (Globorotalia nicolae, Globor. miotumida group, Turborotalita multiloba, and Neogloboquadrina acostaensis), along the series allows us to highlight the succession of the following events:

Event 1: It corresponds to the first presence of Globorotalia nicolae (FO Globorotalia nicolae). It was observed at the bottom of the section, precisely in the sample MES 3. Its astronomical age is 6.83 Ma (Sierro et al., 2001; Blanc-Valleron et al., 2002; Lourens et al., 2004; Lirer et al., 2019);

Event 2: The disappearance of Globorotalia nicolae (LO Globorotalia nicolae) is identified in sample MES 8. This event, dated at 6.712 Ma, has been documented by Sierro et al. (2001), Blanc-Valleron et al. (2002), Lourens et al. (2004), and Lirer et al. (2019);

Event 3: The Globorotalia miotumida group is present and sometimes abundant from the base of the section. The event 3 is defined by its last occurrence (LO Globorotalia miotumida gr.), located in sample MES 18. The astronomical age of LO Globorotalia miotumida gr. is 6.52 Ma (Sierro et al., 2001; Lourens et al., 2004);

Event 4: The first presence of Turborotalita multiloba (FCO T. multiloba) is observed in the MES 24 sample. Sierro et al. (2001), Lourens et al. (2004), and Lirer et al. (2019) have reported this event, with an astronomical age of 6.42 Ma;

Event 5: It is characterized by the sinister to dextral coiling change of Neogloboquadrina acostaensis (S/D N. acostaensis). It was identified in sample MES 28. This event, astronomically dated at 6.358 Ma, has been observed in many pre-evaporitic Messinian sedimentary series in the Mediterranean (Krijgsman et al., 1999a, 1999b; Hilgen & Krijgsman, 1999; Sierro et al., 2001; Lourens et al., 2004; Drinia et al., 2007; Hüsing et al., 2009; Corbí & Soria, 2016; Lirer et al., 2019);

Event 6: The last identified is marked by the first significant reappearance of the sinisterly coiled Neogloboquadrina acostaensis ("sinistral Neogloboquadrina acostaensis influx"). This event was located in sample MES 34, and its astronomical age is 6.12 Ma (Sierro et al., 2001; Lourens et al., 2004).

From the succession of these biostratigraphic bioevents, we could date this section to the pre-evaporitic Messinian with an estimated age of 7.08 to 6.08 Ma. The age of 6.08 Ma corresponds to the base of the Halimeda Limestone (Assen et al., 2006). This biostratigraphic analysis identified new biostratigraphic events and confirmed the results of previous work (Münch et al., 2001; Assen et al., 2006).

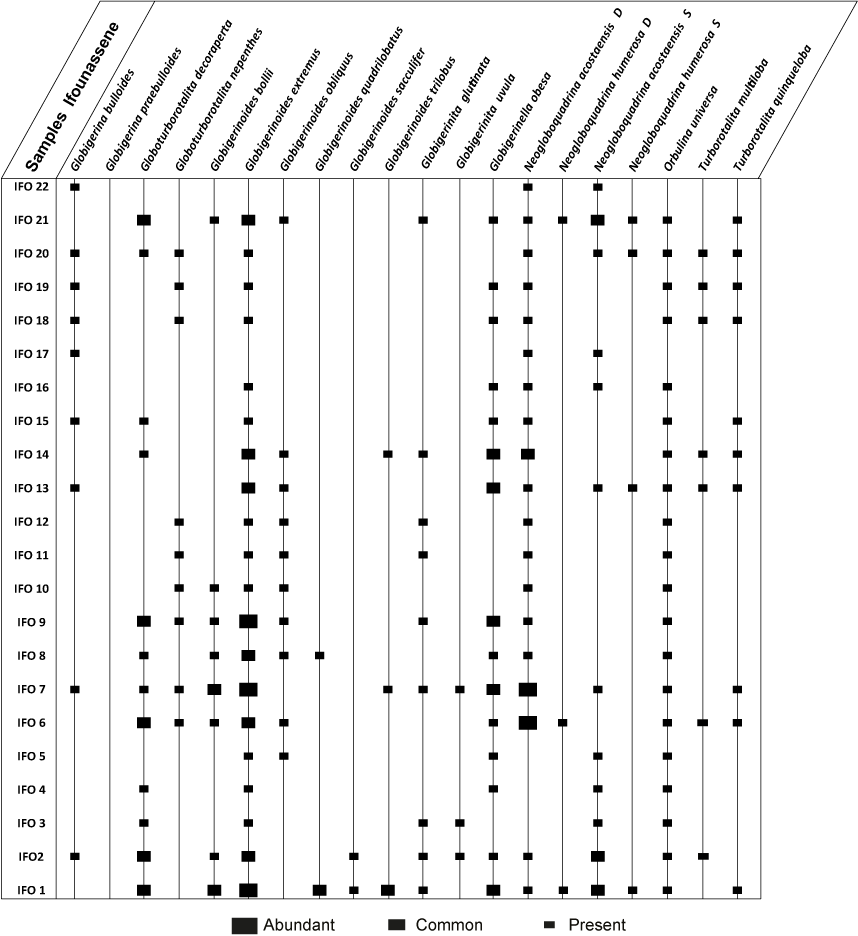

Microfaunal analysis from the Ifounassene section reveals an average to low abundance and diversity of planktonic foraminifera. Nineteen species and eight genera were identified. The washed residues are composed of planktonic and benthic foraminifera, some ostracods, mollusc fragments, sponge spicules, and urchin

radioles. Towards the top of the section the microfauna becomes rare to absent

(from IFO 22 to IFO 25). The vertical distribution of foraminiferal species is illustrated in Table

3. Planktonic foraminifera assemblages in the Ifounassene section are characterized by average to low diversity, with a Shannon

Diversity Index of approximately 1.6

(Fig. 3

![]() ). Some samples showed a high diversity in the order of

2.3. The Planktonic/Benthic ratio oscillates between 10 and 60%. The planktonic foraminifera association is mainly composed of globular forms such as Globigerinoides, Neogloboquadrina, and Turborotalita.

). Some samples showed a high diversity in the order of

2.3. The Planktonic/Benthic ratio oscillates between 10 and 60%. The planktonic foraminifera association is mainly composed of globular forms such as Globigerinoides, Neogloboquadrina, and Turborotalita.

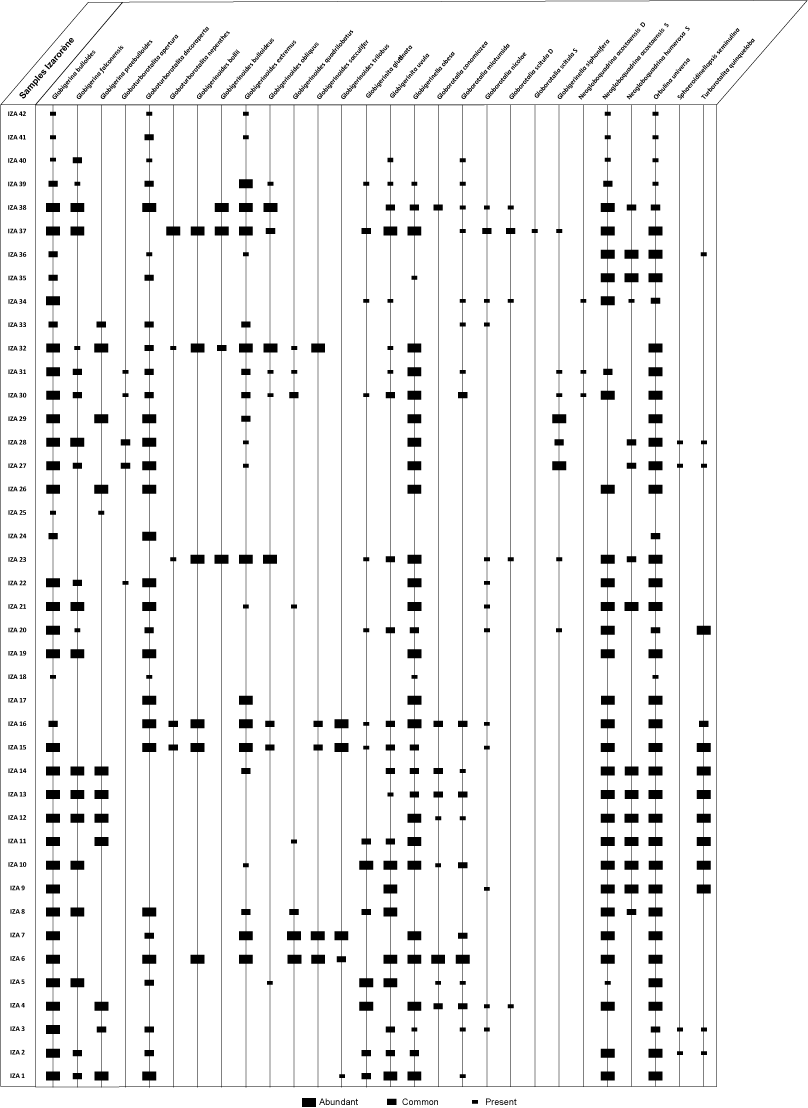

Table 3: Distribution of planktonic foraminifera in the Ifounassene section.

Biostratigraphic analysis and dating: Based on the vertical evolution of the marker species and the qualitative and quantitative analyses, the first presence of Turborotalita multiloba was observed from IFO 2, always associated with Turborotalita quinqueloba. Therefore, the FCO T. multiloba event is recorded at the IFO 2 sample. Furthermore, the vertical evolution of the percentage of Neogloboquadrina acostaensis sinistral and dextral forms of the studied samples expresses that the biostratigraphic event "coiling change of Neogloboquadrina acostaensis sin/dex (S/D N. acostaensis)" is located in sample IFO 6. The first significant reappearance of the sinistral coiling of Neogloboquadrina acostaensis (sinistral influx Neogloboquadrina acostaensis) was observed in sample IFO 21. From these biostratigraphic results, the Ifounassene section is dated to the pre-evaporitic Messinian with an estimated age of 6.52 to 6.08 Ma. This dating confirms the results of Assen et al. (2006).

The detailed analysis of the planktonic foraminiferal assemblages in the Izarorène section reveals significant richness in both species and individuals. A total of 30 species from 10 genera were

identified. The microfauna consists of planktonic and benthic foraminifera, along with some ostracods, fragments of bivalves, and urchin

radioles. Planktonic foraminiferal assemblages in the Izarorène section are characterized by moderate to high diversity, with Shannon Diversity Index varying between 1.4 and 2.4. The Planktonic/Benthic ratio is generally high, varying between 70 and 90%

(Fig. 3

![]() ). Globogerina bulloides, often associated with Globig. falconensis, is well represented in most samples, with significant abundances in some levels. However, periods of high abundance of Globig. bulloides alternate with periods where this species is poorly documented. This information will be utilized in the discussion. The vertical distribution of foraminiferal species is illustrated in

Table 4.

). Globogerina bulloides, often associated with Globig. falconensis, is well represented in most samples, with significant abundances in some levels. However, periods of high abundance of Globig. bulloides alternate with periods where this species is poorly documented. This information will be utilized in the discussion. The vertical distribution of foraminiferal species is illustrated in

Table 4.

Table 4: Distribution of planktonic foraminifera in the Izarorène section.

Biostratigraphic analysis and dating: The stratigraphic distribution and quantitative analyses of planktonic foraminiferal species, particularly the markers, reveals the presence of Globorotalia nicolae, the Globor. miotumida group, and Neogloboquadrina acostaensis. The examination highlights the succession of three significant biostratigraphic events. In the lower part of the Izarorène section, the first occurrence (FO) of Globorotalia nicolae was situated in sample IZA 3, whereas its last common occurrence (LO Globor. nicolae) is above the last massive diatomite (sample IZA 38). Globor. miotumida group is present from the base of the section, with its last occurrence (LO Globor. miotumida gr.) recorded in sample IZA 40. The succession of these bioevents allows us to attribute the Izarorène section to the pre-evaporitic Messinian with an estimated age of 7.24 to 6.35 Ma. These biostratigraphic findings refine and enhance previous dating efforts (Barhoun et al., 1999; Assen et al., 2006).

The correlation of the studied sections shows minor variations in thickness and the progressive installation of the degradation in environmental conditions, as evidenced by the decrease in the abundance and diversity of planktonic species and sometimes the microfauna is rare to absent. These unfavorable conditions for the proliferation of planktonic microfauna are related to the Messinian salinity crisis

(Fig. 4

![]() ). Within the interval 6.83-6.52 Ma, the thickness is 36 m in the Izarorène section and about 30 m in

Messadit. The environmental conditions indicate a relatively open marine environment probably subjected to the action of upwellings as shown by the

P/P+B ratio and the diversity index as well as the abundance of Globigerina bulloides and Globigerina falconensis. Indeed, Globigerina bulloides is a species that proliferates in cold, rich nutrient waters and is often used as an indicator of upwellings (Thiede,

1983; Prell, 1984). Conversely, from 6.52 Ma to 6.12 Ma, the thickness is around 20 m in the Messadit section. The

P/P+B ratio is average to low, planktonic foraminifera are low in abundance and diversity, particularly after 6.35 Ma, indicating a shallower marine environment (Gibson,

1989). From 6.12 Ma the planktonic microfauna is rare to absent because of deteriorating marine conditions caused by reduced water inflow from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea resulting in widespread salt precipitation and a decrease in Mediterranean Sea-level due to evaporation. Furthermore, the end of the diatom bloom was reported around 6.11 Ma by Assen et al. (2006), followed by the installation of the algal level of

Halimeda. These events indicate the closure of the open marine environment in the Melilla-Nador basin and the degradation of environmental conditions in relation to the Messinian salinity

crisis.

). Within the interval 6.83-6.52 Ma, the thickness is 36 m in the Izarorène section and about 30 m in

Messadit. The environmental conditions indicate a relatively open marine environment probably subjected to the action of upwellings as shown by the

P/P+B ratio and the diversity index as well as the abundance of Globigerina bulloides and Globigerina falconensis. Indeed, Globigerina bulloides is a species that proliferates in cold, rich nutrient waters and is often used as an indicator of upwellings (Thiede,

1983; Prell, 1984). Conversely, from 6.52 Ma to 6.12 Ma, the thickness is around 20 m in the Messadit section. The

P/P+B ratio is average to low, planktonic foraminifera are low in abundance and diversity, particularly after 6.35 Ma, indicating a shallower marine environment (Gibson,

1989). From 6.12 Ma the planktonic microfauna is rare to absent because of deteriorating marine conditions caused by reduced water inflow from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea resulting in widespread salt precipitation and a decrease in Mediterranean Sea-level due to evaporation. Furthermore, the end of the diatom bloom was reported around 6.11 Ma by Assen et al. (2006), followed by the installation of the algal level of

Halimeda. These events indicate the closure of the open marine environment in the Melilla-Nador basin and the degradation of environmental conditions in relation to the Messinian salinity

crisis.

|

Figure 4:

Correlations of the studied sections. |

On all the samples processed, 13 from the Ifounassene section contained sufficient pollen, spores, and dinocysts for analysis. The samples from the Izarorène and Messadet sections, however, exhibited a low abundance of palynomorphs and were studied in terms of palynofacies.

The palynofacies study of 13 levels from the Izarorène section reveals a richness in

AOM, reaching up to 70%, except for levels IZA 2, 23, and 26, where the BOM exceeds 45%

(Fig. 5

![]() ). Samples from the Messadit section were found to be poor in palynomorphs. The palynofacies study

indicates abundant AOM in the lower part of the section, reaching 70%, gradually decreasing towards the upper part, reaching 10%

(Fig. 5

). Samples from the Messadit section were found to be poor in palynomorphs. The palynofacies study

indicates abundant AOM in the lower part of the section, reaching 70%, gradually decreasing towards the upper part, reaching 10%

(Fig. 5

![]() ).

Conversely, BOM follows the opposite trend. In the Messadit section, starting from MES 9, there is an alternation between the abundance of continental

(BOM, WOM, and COM) and marine (AOM) inputs. The content of woody debris (WOM) and cellular organic matter is low, varying between 5 and 20%.

).

Conversely, BOM follows the opposite trend. In the Messadit section, starting from MES 9, there is an alternation between the abundance of continental

(BOM, WOM, and COM) and marine (AOM) inputs. The content of woody debris (WOM) and cellular organic matter is low, varying between 5 and 20%.

|

Figure 5:

Palynofacies of the studied sections. |

Pollen grains and spores: Out of 23 samples collected, only 13 yielded palynomorphs. The pollen flora comprises 45 taxa

(Figs. 6

![]() -

7

-

7

![]() ). The floristic image reflected by the pollen spectra is predominantly homogeneous

(Figs. 6

). The floristic image reflected by the pollen spectra is predominantly homogeneous

(Figs. 6

![]() -

7

-

7

![]() ). The synthetic diagram

indicates richness in herbaceous plants, Pinus, mesotherms, and mega-mesothems with sporadic presence of megatherms

(Fig. 7

). The synthetic diagram

indicates richness in herbaceous plants, Pinus, mesotherms, and mega-mesothems with sporadic presence of megatherms

(Fig. 7

![]() ). Pinus constitutes 37% of the total, exhibiting a decrease in the IFO 1 and IFO 8 samples

(Fig. 7

). Pinus constitutes 37% of the total, exhibiting a decrease in the IFO 1 and IFO 8 samples

(Fig. 7

![]() ). Cathaya pollen is consistently present (0 to 6%) whereas Cupressaceae pollen is rare. High-altitude conifer pollen (Picea, Tsuga, Abies) was not

detected. Megatherm elements, including Acantaceae, Icacinaceae, and Sapindaceae, are sporadic, not exceeding 1%. In contrast, Engelhardia dominates (0 to 19%) over the other

mega-mesothermal elements (e.g., Taxodium, Araliaceae,

Hamamelidaceae, Myrica, Arecaceae, Sapotaceae), which are represented by a

lower percentage. Mesothermal elements are characterized by the prevalence of Quercus (3 to 13%),

alongside the presence of Ericaceae, Alnus, Buxus, Populus, Carya, Ulmus, Acer, and Juglans.

Mediterranean xerophytes, including Pistacia, Cistus, Phillyrea, and Ceratonnia, are present with prevailing pollen grains of Quercus coccifera and Olea.

Poaceae (5 to 40%) and Amaranthaceae-Chenopodiaceae (4 to 19.5%) dominate the pollen spectra. Other herbs

(Asteraceae Asteroideae, Asteraceae Cichoroideae, Apiaceae, Lamiaceae, Rumex,

Brassicaceae, Helianthemum, and Cyperaceae) are represented with low frequencies, except for the Plantago genus, reaching

13%. Lygeum, Calligonum, Artemisia, and Ephedra are found in almost all samples without exceeding

4%. Pteridophyte spores vary between 0 and 30%. Botryococcus is present

discontinuously.

). Cathaya pollen is consistently present (0 to 6%) whereas Cupressaceae pollen is rare. High-altitude conifer pollen (Picea, Tsuga, Abies) was not

detected. Megatherm elements, including Acantaceae, Icacinaceae, and Sapindaceae, are sporadic, not exceeding 1%. In contrast, Engelhardia dominates (0 to 19%) over the other

mega-mesothermal elements (e.g., Taxodium, Araliaceae,

Hamamelidaceae, Myrica, Arecaceae, Sapotaceae), which are represented by a

lower percentage. Mesothermal elements are characterized by the prevalence of Quercus (3 to 13%),

alongside the presence of Ericaceae, Alnus, Buxus, Populus, Carya, Ulmus, Acer, and Juglans.

Mediterranean xerophytes, including Pistacia, Cistus, Phillyrea, and Ceratonnia, are present with prevailing pollen grains of Quercus coccifera and Olea.

Poaceae (5 to 40%) and Amaranthaceae-Chenopodiaceae (4 to 19.5%) dominate the pollen spectra. Other herbs

(Asteraceae Asteroideae, Asteraceae Cichoroideae, Apiaceae, Lamiaceae, Rumex,

Brassicaceae, Helianthemum, and Cyperaceae) are represented with low frequencies, except for the Plantago genus, reaching

13%. Lygeum, Calligonum, Artemisia, and Ephedra are found in almost all samples without exceeding

4%. Pteridophyte spores vary between 0 and 30%. Botryococcus is present

discontinuously.

|

Figure 6: Detailed pollen diagram of the Ifounassene

section.

|

|

Figure 7:

Synthetic diagram of the Ifounassene section. |

Dinocysts: The D/S curve shows consistently low values, indicative of a continental influence, except in samples IFO 2, IFO 6, and IFO 11, where the ratio exceeds 0.5, suggesting a marine influence

(Fig. 9

![]() ). The G/P curve shows ratios ranging between 0.92 and 1.00 in all samples

(Fig. 9

). The G/P curve shows ratios ranging between 0.92 and 1.00 in all samples

(Fig. 9

![]() ). The prevalence of Gonyaulocaceae indicates an open marine

environment. Dinocyst assemblages consist mainly of neritic taxa, including Spiniferites (13-52%), Pixydinopsis psilata (6-56%), Operculodinium israelianum (0-3.22%), Selenopemphix nephroides (0-6%), Lingulodinium machaerophorum (1-49%), and Polysphaeridium zoharyi (0-8.6%)

(Fig. 8

). The prevalence of Gonyaulocaceae indicates an open marine

environment. Dinocyst assemblages consist mainly of neritic taxa, including Spiniferites (13-52%), Pixydinopsis psilata (6-56%), Operculodinium israelianum (0-3.22%), Selenopemphix nephroides (0-6%), Lingulodinium machaerophorum (1-49%), and Polysphaeridium zoharyi (0-8.6%)

(Fig. 8

![]() ). Oceanic taxa are sparsely represented. These neritic dinocyst associations have been documented during the Early Messinian in Morocco at the Rifian corridor, reflecting a neritic environment (Warny,

1999; Warny et al., 2003, Bachiri Taoufiq,

2000; Targhi et al., 2021,

2023). These dinocyst associations collectively suggest the existence of a neritic marine

environment.

). Oceanic taxa are sparsely represented. These neritic dinocyst associations have been documented during the Early Messinian in Morocco at the Rifian corridor, reflecting a neritic environment (Warny,

1999; Warny et al., 2003, Bachiri Taoufiq,

2000; Targhi et al., 2021,

2023). These dinocyst associations collectively suggest the existence of a neritic marine

environment.

Distality index: The abundance of continental inputs indicates that the depositional environment of the Ifounassene section was

epicontinental. The D/S curve consistently shows low values, reflecting a continental influence, except in samples IFO 2, IFO 6, and IFO 11, where the ratio

exceeds 0.5, suggesting a marine influence

(Fig. 9

![]() ). The IN/ON distality index

(Fig. 9

). The IN/ON distality index

(Fig. 9

![]() ) varies between 0.1 and 0.8; indicating an external platform environment, except in levels 3, 7, 4.5, 8, and 12, where the ratio increases,

suggesting a shift towards a proximal neritic environment. This trend aligns well with the Planktonic/Benthic ratio

(Fig. 3

) varies between 0.1 and 0.8; indicating an external platform environment, except in levels 3, 7, 4.5, 8, and 12, where the ratio increases,

suggesting a shift towards a proximal neritic environment. This trend aligns well with the Planktonic/Benthic ratio

(Fig. 3

![]() ).

).

Temperature index: The temperature index varies between 0.8 and 1

(Fig. 9

![]() ), indicating a predominance of warm water taxa and warm thermal conditions at the water surface. In samples 2, 11, and particularly 6, a slight decrease in the W/C ratio is observed due to the appearance of cold taxa such as Operculodinium centrocarpum and Nematospheropsis

labyrinthea.

), indicating a predominance of warm water taxa and warm thermal conditions at the water surface. In samples 2, 11, and particularly 6, a slight decrease in the W/C ratio is observed due to the appearance of cold taxa such as Operculodinium centrocarpum and Nematospheropsis

labyrinthea.

|

Figure 8:

Detailed dinocyst diagram of the Ifounassene section. |

|

Figure 9:

Curves of P/A, D/S, G/P ratios and diversity, W/C (temperature), IN/ON

(distality) index of the Ifounassene section |

Ifounassene Palynofacies: The palynofacies of Ifounassene section exhibits a recurring shift between the prevalence of amorphous organic matter and the abundance of black organic matter (BOM) and cellular debris (COM)

(Fig. 5

![]() ). The richness of this organic matter indicates a strong continental influence, supporting the dinocyst data suggesting a continental-influenced neritic environment. Presumably, when conditions become less turbulent, they favor the development of

AOM.

). The richness of this organic matter indicates a strong continental influence, supporting the dinocyst data suggesting a continental-influenced neritic environment. Presumably, when conditions become less turbulent, they favor the development of

AOM.

The evolution of the marine environment in the Melilla-Nador basin during the pre-evaporitic Messinian is proposed in three stages based the qualitative and quantitative analyses of planktonic foraminifera, spores, pollen grains, dinocysts, and palynofacies.

Stage 1, from 6.83 to 6.52 Ma: This interval is characterized by three biostratigraphic events: First Occurrence (FO) of Globorotalia nicolae, Last Occurrence (LO) of Globor. nicolae, and Last Occurrence (LO) of Globor. miotumida group. It spans from the onset of cyclic marine sedimentation in the Melilla-Nador basin to the initial changes in diatom associations (Assen et al., 2006). The P/P+B ratio is often high, and the diversity is normal, occasionally marked by an abundance of Globigerina bulloides and Globig. falconensis, indicating a relatively open marine environment likely affected by upwellings. Benthic foraminifera also register episodes of upwellings, characterized by the prevalence of bolivinids and buliminids (Rachid et al., 1997). During this interval (6.83-6.52 Ma), sediment thickness varies between 30 and 36 m. The environmental conditions suggest a relatively open marine setting, as evidenced by the consistently high P/P+B ratio. The presence of Globigerina bulloides and Globig. falconensis implies the impact of upwelling, with Globog. bulloides often considered an indicator of cold, nutrient-rich waters and used as an upwelling indicator (Thiede, 1983; Prell, 1984). The examination of diatom assemblages and benthic foraminifera provides additional insights into the dynamics of Messinian upwellings in this basin (Rachid et al., 1997; Saint-Martin et al., 2003). The palynofacies is characterized by an overall abundance of amorphous organic matter, indicating a distal and calm environment. However, exceptions are noted in levels IZA 2, IZA 23, and IZA 26, where continental inputs (MOX, MOV, and MOB) dominate, reflecting an agitated and proximal environment at these levels. Additionally, the lower part of the Messadit section exhibits calm and distal conditions conducive to the development of amorphous organic matter. These findings align with the diatom data, which feature oceanic and oceanic-neritic species, along with silicoflagellates, confirming the existence of a distinct marine environment connected to the oceanic domain (Saint-Martin et al., 2003). Similar wet and warm conditions with oceanic environments and an external neritic trend have been observed in Salé (NW Morocco) between 7.3 and 6.5 Ma (Warny et al., 2003), the Guadalquivir Basin in Spain between 6.8 and 6.5 Ma (Jiménez-Moreno et al., 2013), and in the central Mediterranean between 7.6 and 6.5 Ma (Bertini & Menichetti, 2015).

Stage 2, from 6.52 to 6.35 Ma: This stage is characterized by the succession of two biostratigraphic events observed in the Messadit and Ifounassene sections: First Common Occurrence (FCO) of Turborotalia multiloba and the coiling change S/D Neogloboquadrina acostaensis. From 6.52 Ma onwards, the P/P+B ratio becomes average to low, and planktonic foraminifera are less abundant and diversified, suggesting a shallower environment. Continental inputs, including pollen grains, spores, and plant debris dominate, prevail. They indicate a marine environment very close to the continent with significant fluvial inputs. Dinocyst associations in Ifounassene (IFO 1 to IFO 6 samples) suggest a neritic environment with warm surface waters. Distality indices (D/S, ID, Pinaceae) reveal an alternation between proximal and distal neritic environments. Comparisons with sections in Salé, Briqueterie site (NW Morocco, Warny et al., 2003), and the Guadalquivir basin (Spain, Jiménez-Moreno et al., 2013) indicate that the percentage of pine trees in Ifounassene (not exceeding 35%) is very low. This implies that, from 6.52 Ma, the bathymetry in the Messinian marl-diatomite series gradually decreases due to the reduction of Atlantic water inflow and the uplift of the basin.

Stage 3, from 6.35 Ma to 6.12 Ma: From 6.35 Ma, planktonic foraminifera are poorly represented compared to benthic foraminifera. Regarding palynofacies, from IFO 6 to IFO 25, continental inputs continue to dominate compared to Messadit section. Distality indices (D/S, ID, pins) consistently show an alternation between proximal and distal neritic environments. Despite the closure of the two Rifian Corridors, i.e., the South Rifian Corridor at 7.1-6.9 Ma and the North Rifian Corridor from 7.35 to 7.00 Ma (Cappella et al., 2018, 2019), the basin remains open to the Atlantic and likely receives input through the Strait of Gibraltar (Capella et al., 2018; Krijgsman et al., 2018). From 6.12 Ma, planktonic microfauna becomes rare to absent due to deteriorating marine conditions. Additionally, Assen et al. (2006) reported the end of the diatom bloom around 6.11 Ma, followed by the establishment of the Halimeda algal level, indicating the closure of the open marine environment in the Melilla-Nador basin and the deterioration of environmental conditions associated with the Messinian salinity crisis.

Vegetal landscapes: The pollen study of the pre-evaporitic Messinian deposits of the Ifounassene section reveals the presence of

plant elements living today in the American and Asian regions (Cathaya, Engelhardia,

Sapotaceae, Arecaceae, and Hamamelidaceae), alongside elements currently living in Europe (Quercus,

Ericaceae, Alnus, Buxus, Populus, Carya, Ulmus, Acer, and Juglans) or the Mediterranean regions (Olea, Quercus type ilex-coccifera, Cistus, Pistacia, Phillyrea, and Ceratonnia). These same plant taxa have also been recorded in the Moroccan Messinian at the Rifain corridor (Bachiri Taoufiq,

2000; Bachiri Taoufiq et al.,

2008; Suc et al., 2018; Targhi et al.,

2021) and Boudinar basin (Achalhi et al.,

2016). Sub-desert taxa were also identified (Lygeum, Calligonum, Artemisia, and Ephedra). Taxa representing open plant formations

(Poaceae, Amaranthaceae-Chenopodiaceae, Plantago, etc.)

constitute a significant percentage. The mangrove element Avicennia, encountered in the northwestern Mediterranean from the Early to the Middle Miocene (Bessedik,

1984, 1985; Bessedik et al.,

1984), and in the south and western Mediterranean

(Spain, Sicily, Algeria, and Morocco) until the Messinian (Suc & Bessais,

1990; Chikhi, 1992a,

1992b; Bachiri Taoufiq et al.,

2001a, 2001b; Jiménez-Moreno et al.,

2013; Targhi et al.,

2021, 2023), has not been recorded in this pre-evaporitic Messinian

section. The presence of a mixture of taxa with different thermal and hydric requirements can be explained by a certain staging of the vegetation (Bessedik,

1985; Suc, 1986,

1989)

and, consequently, a depositional environment relatively near the littoral and the mountain

massifs. Detailed analysis of the diagrams (Figs. 6

![]() - 7

- 7

![]() ) reveals two types of formations that succeeded each other behind the coral formations.

) reveals two types of formations that succeeded each other behind the coral formations.

Open littoral lowland formation: The littoral associations comprised xerophilous and/or halophilous herbaceous plants, including Poaceae, Amaranthaceae-Chenopodiaceae Plantago, and Asteraceae (Cichorioideae and Asteroideae). The prevalence of these pollen grains indicates the presence of a vast littoral plain. The occurrence of sub-desert plants such as Lygeum, Calligonum, Artemisia, and Ephedra confirms the arid nature of the environment. Trees and shrubs such as Arecaceae and Sapotaceae could also coexist in more humid areas. This open vegetation likely transitioned to a formation with Mediterranean elements, including Olea, Quercus type ilex-coccifera, Cistus, Pistacia, Phillyrea, and Ceratonia.

Arboreal formation: In areas relatively distant from the littoral, above the Mediterranean grouping and on the first reliefs, more forested associations of Pinus, Quercus, Ericaceae, Alnus, Buxus, Populus, Carya, Ulmus, Acer, Juglans, and evergreen elements (Sapotaceae, Arecaceae, Ilex) were likely present (Bachiri Taoufiq, 2000; Suc et al., 2018; Targhi et al., 2021). At higher elevations, towards the hinterland, this mixed mesophilic forest probably transitioned to a vegetation dominated by thermophilic elements like Taxodium, Cathaya, Engelhardia, Hamamelidaceae, Quercus, and Cupressaceae. The absence of high-altitude trees (Cedrus, Abies, and Picea) suggests a relatively low relief.

Climate: The pollen flora identified in Ifounassene section indicates a hot and dry

climate,

characterized by the presence of thermophilic elements such as Taxodium, Cathaya, Engelhardia,

Hamamelidaceae, Quercus, and Cupressaceae,

along with the abundance of taxa of dry environments such as herbaceous

sub-desert elements (Artemisia, Ephedra, Lygeum, and Calligonum).

Similar climatic conditions were observed in the southwestern Mediterranean in Morocco and Algeria during the Messinian (Chikhi,

1992a, 1992b; Warny,

1999; Warny et al., 2003; Bachiri Taoufiq et al.,

2001a, 2001b, 2008; Achalhi et al.,

2016; Suc et al., 2018; Targhi et al.,

2021). In the Ifounassene section, the absence of microthermals and the presence of

megathermals, megamesothermals, and mesothermals are notable. This observation leads us to estimate an average temperature

ranging from 20 to 24°C, consistent with the presence of guide taxa such as Lygeum (Fauquette et al.,

1999). At the middle altitude where Engelhardtia lived (Fauquette et al.,

1999), temperatures

consistently remained high (18-21°C), and precipitation levels were higher (600-700 mm per

year). These climatic conditions

bear similarity to those encountered in the Early Messinian in Algeria (Chikhi,

1992a, 1992b); Morocco (Warny,

1999; Bachiri Taoufiq, 2000), Sicily (Suc & Bessais,

1990; Bertini et al., 1998), and Spain (Jiménez-Moreno et al.,

2013). These estimates

align with results from transfer function results applied to the Upper Miocene (Fauquette et al.,

2007; Suc et al., 2018) and the Lower Pliocene (Fauquette et al.,

1999), indicating a mean annual temperature of

approximately 23°C and annual precipitation around 450 mm. Precipitation values were estimated the ratio P/A was

used. In the Ifounassene section, the Poaceae/ Asteraceae ratio is generally less than 20, except in levels IFO 7 and IFO 12

samples, where it is greater than or equal to 20

(Fig. 9

![]() ). In the former case, rainfall is estimated to be less than 500 mm

while, in both levels, it exceeds 500 mm/year. A comparison of the Ifounassene section ratio with those of the lower Messinian in the southern Rifian corridor (Bachiri,

2000; Bachiri et al.,

2008; Targhi et al., 2021,

2023) indicates that climatic conditions in the Melilla-Nador basin were comparatively less

dry. Moreover, in the Melilla-Nador basin located in the

north, tropical elements such as Avicennia (found in the Tortonian and Lower Messinian along the southern Rifian corridor) are rare, and subtropical elements are less diverse. This implies a slight decrease in temperature and an increase in humidity from the south to the north of

Morocco. These

findings align with quantifications confirming the existence of an increasing latitudinal gradient of temperature and dryness from north to

south,

similar to the current gradient (Jiménez-Moreno et al.,

2013; Bertini & Menichetti,

2015; Suc et al., 2018).

). In the former case, rainfall is estimated to be less than 500 mm

while, in both levels, it exceeds 500 mm/year. A comparison of the Ifounassene section ratio with those of the lower Messinian in the southern Rifian corridor (Bachiri,

2000; Bachiri et al.,

2008; Targhi et al., 2021,

2023) indicates that climatic conditions in the Melilla-Nador basin were comparatively less

dry. Moreover, in the Melilla-Nador basin located in the

north, tropical elements such as Avicennia (found in the Tortonian and Lower Messinian along the southern Rifian corridor) are rare, and subtropical elements are less diverse. This implies a slight decrease in temperature and an increase in humidity from the south to the north of

Morocco. These

findings align with quantifications confirming the existence of an increasing latitudinal gradient of temperature and dryness from north to

south,

similar to the current gradient (Jiménez-Moreno et al.,

2013; Bertini & Menichetti,

2015; Suc et al., 2018).

The detailed study of planktonic foraminifera, spores, pollen grains, dinocysts, and palynofacies on three marl-diatomite sedimentary series in the Melilla-Nador Basin enhances our understanding of the evolution of marine and continental environments during the pre-evaporitic Messinian in the Western Mediterranean. During the interval 6.83-6.52 Ma, the marine environment in the basin was relatively deep and open, likely influenced by upwellings, rich in planktonic foraminifera, oceanic and oceanic-meridian diatoms, and MOA. Periodically, continental inputs occurred, suggesting a shift towards a proximal environment. Warm surface water conditions are indicated by the presence of coral reefs.

Starting from 6.52 Ma, the significance and diversity of planktonic foraminifera decreased, boreal diatoms transitioned to tropical diatoms, and carbonate platform reefs prograded. Alternating with amorphous organic matter, continental inputs gradually dominated, indicating a marine environment close to the continent with significant fluvial inputs. Distality indexes suggest alternation between proximal and distal neritic environments. Surface water conditions remained warm and tropical, and the continental environment exhibited an open vegetation landscape dominated by herbaceous plants, reflecting a tropical to subtropical arid climate conducive to erosion.

Post 6.35 Ma, the environment evolved towards the degradation of marine conditions, as evidenced by the rarity of the planktonic microfauna. At 6.08 Ma, the formation of Halimeda algal beds commenced, overlying the marl-diatomite cyclic sequence.

In summary, during the pre-evaporitic Messinian, the Melilla-Nador Basin underwent the influence of two main factors contributing to the formation of the marl-diatomite series: 1) tectonic activity causing a decrease in bathymetry and progressive uplift and 2) global parameters including 2a) a warm, arid climate favoring herbaceous plant spread, and 2b) episodic oceanographic phenomena such as upwelling. These findings support and align with previous results reported by Pelligrino et al. (2018).

This work benefited from the technical equipment of the Geosciences and Applications Laboratory, Geology Department, Faculty of Sciences Ben M'sik, Hassan II University of Casablanca (Morocco). Many thanks are extended to the individuals (reviewers and editors) who provided constructive comments to enhance the quality of this paper.

Achalhi M., Münch P., Cornée J.-J., Azdimousa A., Melinte-Dobrinescu M., Quillévéré F., Drinia H., Fauquette S., Jiménez-Moreno G., Merzeraud G., Moussa A.B., El Karim Y. & Feddi N. (2016).- The late Miocene Mediterranean-Atlantic connections through the North Rifian Corridor: New insights from the Boudinar and Arbaa Taourirt basins (northeastern Rif, Morocco).- Palæogeography, Palæoclimatology, Palæoecology, vol. 459, p. 131-152.

Agiadi K., Antonarakou A., Kontakiotis G., Kafousia N., Moissette P., Cornée J.-J., Manoutsoglou E. & Karakitsios V. (2017).- Connectivity controls on the late Miocene eastern Mediterranean fish fauna.- International Journal of Earth Sciences, vol. 106, p. 1147-1159.

Assen E. van, Kuiper K.F., Barhoun N., Krijgsman W. & Sierro F.J. (2006).- Messinian astrochronology of the Melilla Basin: Stepwise restriction of the Mediterranean-Atlantic connection through Morocco.- Palæogeography, Palæoclimatology, Palæoecology, vol. 238, p. 15-31.

Bache F., Gargani J., Suc J.-P., Gorini C., Rabineau M., Popescu S.M., Leroux E., Do Couto D., Jouannic G., Rubino J.-L., Olivet J.-L., Clauzon G., Dos Reis A.T. & Aslanian D. (2015).- Messinian evaporite deposition during sea level rise in the Gulf of Lions (Western Mediterranean).- Marine and Petroleum Geology, vol. 66, no. 1, p. 262-277.

Bachiri Taoufiq N. (2000, unpublished).- Les environnements marins et continentaux du corridor rifain au Miocène supérieur d'après la palynologie.- PhD Thesis, University Hassan II-Mohammedia, Casablanca, 212 p.

Bachiri Taoufiq N. & Barhoun N. ( 2001a).- La végétation, le climat et l'environnement marin au Tortonien dans le bassin de Taza-Guercif (Corridor rifain, Maroc oriental) d'après la palynologie.- Géobios, Villeurbanne, vol. 34, no. 1, p. 13-24.

Bachiri Taoufiq N., Barhoun N. & Suc J.-P. (2008).- Les environnements continentaux du corridor rifain (Maroc) au Miocène supérieur d'après la palynologie.- Geodiversitas, Paris, vol. 30, no. 1, p. 41- 58.

Bachiri Taoufiq N., Barhoun N., Suc J.-P., Méon H., Elaouad Z. & Benbouziane A. (2001b).- Environnement, végétation et climat du Messinien au Maroc.- Paleontologia i Evolució, Sabadell, no. 32-33, p. 127-138.

Barhoun N. (2000).- Biostratigraphie et paléoenvironnement du Miocène supérieur et du Pliocène inférieur du Maroc septentrional : Apport des foraminifères planctoniques.- Thèse d'État ès Sciences, Université Hassan II-Mohammedia, Casablanca, Maroc, 272 p.

Barhoun N., Sierro F.J., El Hajjaji K. & Ben Bouziane A. (1999).- Biostratigraphie et paléoenvironnement du Miocène supérieur du bassin de Zéghanghane (Rif nord-oriental, Maroc) : Apport des foraminifères planctoniques.- Revista Española de Micropaleontologia, Madrid vol. 31, no. 2, p. 279-287.

Bellier J.-P., Mathieu R. & Granier B. (2010).- Short Treatise on Foraminiferology (Essential on modern and fossil Foraminifera) [Court traité de foraminiférologie (L'essentiel sur les foraminifères actuels et fossiles)].- Carnets de Géologie - Notebooks on Geology, Brest, Book 2010/02 (CG2010_B02), 104 p. (10 pls.). DOI: 10.4267/2042/33629

Benson R.H., Rakic El Bied K. & Bonaduce G. (1991).- An important current reversal in the Rifian Corridor (Morocco) at the Tortonian-Messinian boundary: The end of the Tethys Ocean.- Paleoceanography, vol. 6, p. 165-192.

Bertini A., Londeix L., Maniscalco R., Di Stefano A., Suc J.-P., Clauzon G., Gautier F. & Grasso M. (1998).- Paleobiological evidence of depositional conditions in the Salt Member, Gessoso-Solfifera Formation (Messinian, Upper Miocene) of Sicily.- Micropaleontology, vol. 44, no. 4, p. 413-433.

Bertini A. & Menichetti E. (2015).- Palaeoclimate and palaeoenvironments in central Mediterranean during the last 1.6 Ma before the onset of the Messinian Salinity Crisis: A case study from the Northern Apennine foredeep basin.- Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, vol. 218, p. 218-106.

Bessedik M. (1984).- The early Aquitanian and upper Langhian-lower Serravalian environments in the northwestern Mediterranean region.- Paleobiology, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 153-179.

Bessedik M. (1985).- Reconstitution des environnements miocenes des régions nord-ouest méditerranéennes à partir de la palynologie.- Thèse Doctorat Sciences, U.S.T.L., Montpellier, vol. 18, no. 6, 162 p.

Bessedik M., Guinet P. & Suc J.-P. (1984).- Données paléofloristiques en Méditerranée nord-occidentale depuis l'Aquitanien.- Revue de Paléobiologie, Genève, volume special, p. 25-31.

Blanc-Valleron M.-M., Pierre C., Caulet J.-P., Caruso A., Rouchy J.-M., Gespuglio G., Sprovieri R., Pestrea S. & Di Stefano E. (2002).- Sedimentary, stable isotope and micropaleontological records of paleoceanographic change in the Messinian Tripoli Formation (Sicily, Italy).- Palæogeography, Palæoclimatology, Palæoecology, vol. 185, p. 255-286.

Capella W., Barhoun N., Flecker R., Hilgen F., Kouwenhoven T., Matenco L.C., Sierro F.J., Tulbure M.A., Yousfi M.Z. & Krijgsman W. (2018).- Palaeogeographic evolution of the late Miocene Rifian Corridor (Morocco): Reconstructions from surface and subsurface data.- Earth Science Reviews, vol. 180, p. 37-59.

Capella W., Flecker R., Hernandez-Molina F.J., Simon D., Meijer P.T., Rogerson M., Sierro F.J. & Krijgsman W. (2019).- Mediterranean isolation preconditioning the Earth System for late Miocene climate cooling.- Scientific Reports, vol. 9, article 3795, 8 p.

Chikhi H. (1992a).- Palynoflore du Messinien infra-évaporitique de la série marno-diatomitique de Sahaouria (Beni-Chougrane) et de Chabet Bou Seter (Tessala), bassin du Chelif, Algérie.- Thèse, Université d'Oran, 169 p.

Chikhi H. (1992b).- Une palynoflore méditerranéenne à subtropicale au Messinien pré-évaporitique en Algérie.- Géologie Méditerranéenne, Marseille, t. XIX, no. 1, p.19-30.

Choubert G., Faure-Muret A., Hottinger L. & Lecoîntre G. (1966).- Le Néogene du bassin Melilla (Maroc septentrional) et sa signification pour definir la limite Mio-Pliocène au Maroc.- Committee on Mediterranean Neogene stratigraphy, ICS-IUGS, p. 238-249.

CIESM (2008).- The Messinian Salinity Crisis from Mmega-deposits to m.- A Consensus Report, Monaco, vol. 30, p. 168.

Combaz A. (1980).- Les kérogènes vus au microscope.- Édition Technip, Paris, 519 p.

Corbí H. & Soria J.M. (2016).- Late Miocenee early Pliocene planktonic foraminifer event stratigraphy of the Bajo Segura basin: A complete record of the western Mediterranean.- Marine and Petroleum Geology, vol. 77, p. 1010-1027.