This is the 2nd edition (2021 - modified and completed) of the publication issued in 2015.

The Protestant genealogy in Alsace ... remarks and advices

Christian C. Emig *

[Abstract]

Version

Introduction

In Alsace, Protestants have German culture more pronounced than in other religions, because the vast majority are Lutherans from the Augsburg Confession. For all ecclesial acts the language was in German since the Reformation induced by Martin Luther and his translation of the Bible, printed by Gutenberg. The introduction of bilingual offices occurred in the 1950s! I remember the first one in Colmar; only the sermon was in French.

For almost a millennium, Alsace, German soil, was part of Heiliges Römisches Reich deutscher Nation (translated to English as The Holy Roman Empire - but should be complete by adding of the German Nation) since February 2, 962 by Otto I, and partially of the Second and Third Reich. Alsatian genealogies follow the German practice until the early nineteenth century and from 1871 to 1919 and 1939 to 1944. Yet today local laws apply which were inherited from German times and from French occupation, i.e., the Napoleonic Concordat of 1801 and the non-application of the French law of 1905 on secularism. The religious affiliation of the ascendants is crucial knowledge in genealogical research. Outstanding are the "mixed" marriages. Unlike France, Protestants were not a minority in the German Empire; the elected emperor when Catholic had to deal with the Protestant princes. For example, Charles V in 1555 had to enact the famous the principle Cujus regio, ejus religio (whose realm, his religion) on Lutheran request.

Good knowledge of the history of Alsace and of German, its written language always official language, is a basic prelude before beginning the search of Alsatian ascendants. The present paper brings together my knowledge gained during research on my German, including Alsatian, and Swiss families, some are known from the 3rd Century. For all, the border has never been the Rhine River but the "blue line" of the Vosges Mountains (Emig, 2012).

Calendar Year

Before the middle of the 15th century, the year generally began at Christmas, on December 25, sometimes already on January 1, but on March 25 in the Protestant County of Montbéliard until 1564. During the reign of Ferdinand I (1558 -1564), January 1 has been adopted to avoid adverse disparities among the territories of the Holy Roman Empire (Tab. 1).

|

Français

|

Deutsch

|

English

|

|

janvier

|

Jenner, Jänner, Hartung

|

Januar

|

January

|

|

février

|

Hornung

|

Februar

|

February

|

|

mars

|

Lenzmonat, Frühlingsmonat

|

März

|

March

|

|

avril

|

Ostermonat, Osteren

|

April

|

April

|

|

mai

|

Wonnemonat, Blütemonat

|

Mai

|

May

|

|

juin

|

Brachmonat

|

Juni

|

June

|

|

juillet

|

Heumonat, Heuert

|

Juli

|

July

|

|

août

|

Emtemonat, Hitzmonat

|

August

|

August

|

|

septembre ou 7bre

|

Herbstmonat, Fruchtmonat, Herpsten, 7bris

|

September

|

September

|

|

octobre ou 8bre

|

Weinmonat, 8bris

|

Oktober

|

October

|

|

novembre ou 9bre

|

Wintermonat, 9bris

|

November

|

November

|

|

décembre ou Xbre, 10bre

|

Christmonat, Xbris, 10 bris

|

Dezember

|

December

|

Table 1. – Comparison of the names of months in different languages and at different periods. .

From Julian to Gregorian Calendar

In Alsace, the adoption of the Catholic Gregorian calendar occurred between 1583 to 1603 in Catholic possessions and later in Protestant parishes, because it was imposed by the Vatican. The change to the Gregorian calendar occurred from 1682 to 1701 according to the parishes, because before it was possible to distinguish the religious holidays between Lutherans and Catholics (see Appendix 1). In Swiss cantons the conversion took place between 1700 and 1812.

A difference of 10 to 12 days may occur between dates, according to the calendar. Unfortunately softwares may apply the date of the Catholic conversion, e.g., 1583 (see Appendix 1).

Republican or Revolutionary calendar

This calendar is a French exception, imposed even in official Alsatian documents in German. The Republican calendar was used in Alsace from September 22, 1793 to December 31, 1805. It begins with the year II. The former date generally corresponds to the beginning of the civil records that are commonly in German until about 1806; only large towns have used French. In some municipalities, especially in Lower Alsace, revolutionaries months have been translated to German - see Table 2.

| Mois révolutionnaires |

Elsäßer Monat |

Dates |

|

vendémiaire

|

Weinmonat |

22 September ~ 21 October |

|

brumaire

|

Nebelmonat |

22 October ~ 20 November |

|

frimaire

|

Frostmonat, Reifmonat |

21 November ~ 20 Deccember |

|

nivôse

|

Schneemonat |

21 Deccember ~ 19 January |

|

pluviôse

|

Regenmonat |

20 January ~ 18 February

|

|

ventôse

|

Windmonat |

19 February ~ 20 March

|

|

germinal

|

Knospenmonat, Keimmonat |

21 March ~ 19 April

|

|

floréal

|

Blütenmonat, Blumenmonat |

20 April ~ 19 May

|

|

prairial

|

Wiesenmonat |

20 May ~ 18 June

|

|

messidor

|

Erntemonat |

19 June ~ 18 July |

|

thermidor

|

Hitzmonat |

19 July ~ 17 August |

|

fructidor

|

Fruchtemonat |

18 August ~ 16 September |

Table 2. – Comparison of denominations revolutionary months in French and German.

The 5 extra days and the 6th in leap years are not indicated here - see also Table 1.

The Registers

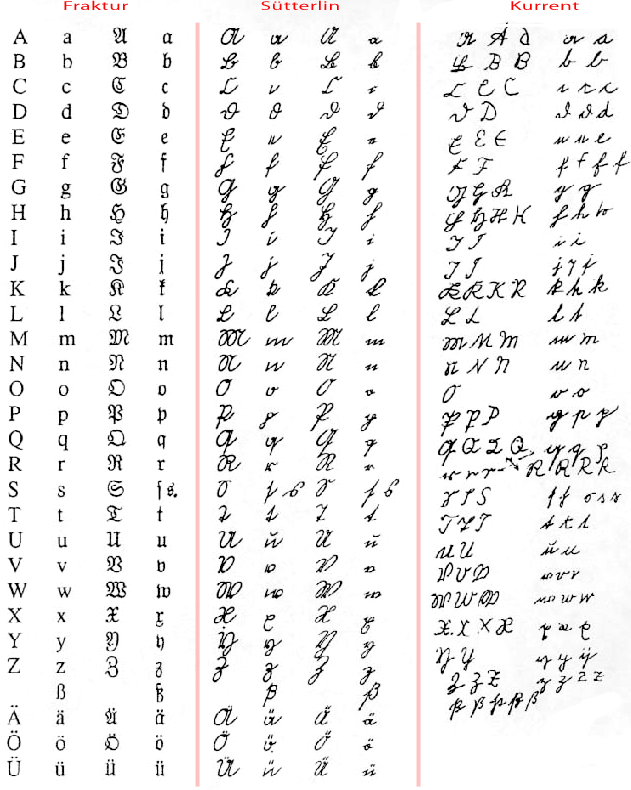

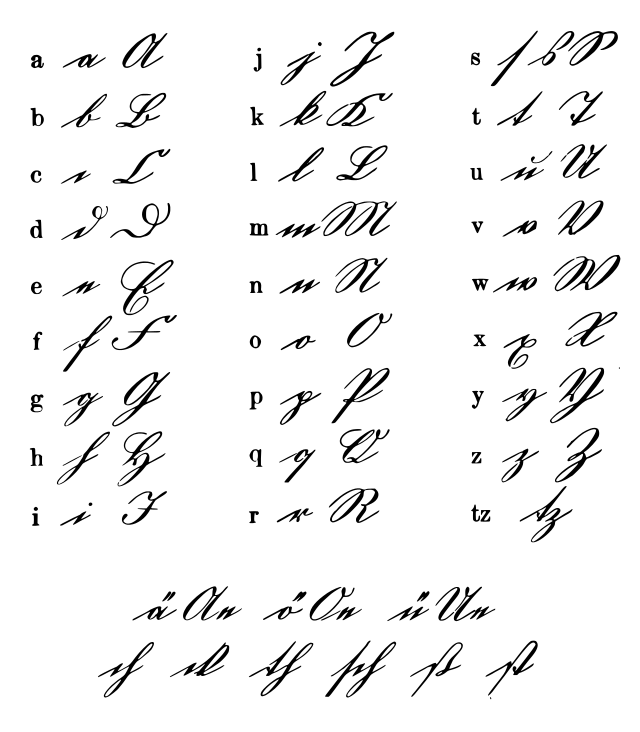

Protestant church records are in German Gothic script (Tab. 3). Examples of different Gothic scripts are represented in the two tables below (Tab. 4 and 5). The palaeographic and linguistic specificities of Alsatian records represent great difficulties for many non-German speaking genealogists, and even for native ones! Misinterpretations often lead to wrong ascendants – plenty of examples occur among the Mormon data as well as in Ancestry.com.

| Periods |

Letter types (fonts) |

|

| 15th century |

textura

|

(a)

|

| end of 15th c. |

Schwabacher

|

|

| beginnnng 16th c. |

Fraktur

|

(b)

|

| 19th century |

Kurrent

|

|

| about 1918 |

Sütterlin

|

|

| from 1941 |

Antiqua (typographic)

Normalschrift (handwriting) |

(c)

|

Table 3. – Main steps of the German Gothic writing. (a) printing characters used (Bible edition); (b) use until the middle of the 20th century; (c) End of the Gothic German by decree of Adolf Hitler in 1941.

Table 4. – Three of the German Gothic writings: Kraktur, Sütterlin, Kurrent (see also Tabl. 5).

Table 5. – Gothic German in Kurrent fonts.

The use of German is easily explained by the fact that less that 5% of the Alsatians had knowledge of French and 95% were only speaking Alsatian and writing German until the middle of the 20th Century. Only in 1859 did the teaching of French became compulsory in Alsace, but a decade later, Alsace returned to Germany (1871 to 1919) and later from 1940 to 1945. For almost all Alsatians the native language is Alsatian (speaking) and German (writing).

The Surnames

In terms of onomastics, there is little difference between Alsatian and German surnames. This is even more evident that many ancestors immigrated to Alsace from other German and Swiss regions, especially after the Thirty Years War (1618–1648) (Fig. 1). Changes in surnames remained exceptional, at least in our families. This patronymic maintenance also applies to members who emigrated to USA and Canada. In terms of onomastics, there is little difference between Alsatian and German surnames. This is even more evident that many ancestors immigrated to Alsace from other German and Swiss regions, especially after the Thirty Years War (1618–1648) (Fig. 1). Changes in surnames remained exceptional, at least in our families. This patronymic maintenance also applies to members who emigrated to USA and Canada.

Fig. 1. – A Phil's cartoon (published with his friendly permission).

Unlike the basic explanations, such as oral transcription by the US administration, Wohlhüter, Nadelhoffer, Wölfersheim, Sturm immigrants, among many others, have not seen their name changed, sometimes maintaining the umlaut. It seems to me that these changes are in fact related to illiteracy as the surname holders more than to the oral transcription of an immigration officer. When using genealogical software, any change in the surname introduces a gap in a family tree, except if variants can be manage by. Genealogists generally use the recent surname for all the ascendants. In France no surname change is allow after the law of the 6 Fructidor an II (August 23, 1794).

The surname in emigrated Anabaptist families is a special case with variations as to between children within the same family (see Appendix). This obviously makes research in basic genealogical data particularly difficult or sterile [1]. In addition, ancestry becomes doubtful, the father-child link is no longer ensured especially in emigration earlier than 19th century. Original records are needed in roder to avoid mistakes in identity".

In the parish registers, the feminization of the surname is made by adding "-in" or "-n" when the name already ends with "i" or "ÿ" [2] (e.g., Wohlhüter and Wohlhüterin ). This form is often the cause of transcription error by considering this female form as patronymic. This practice ended with the establishment of the State-Civil, simultaneously made their surnames final and invariable in form. Since the law of 6 fructidor an II (August 23, 1794) for all citizens first and last names have to be those listed on their birth certificate and consequently cannot be translated but have to be used in the original form.

The umlaut (Umlaut in German) is a diacritic mark composed of two small vertical lines placed above a vowel to indicate a sound change. Be careful that you do not confuse the umlaut with the French tréma (two dots): a diaeresis indicates that a vowel should be pronounced apart from the letter that precedes it. The umlaut modifies the sound of several vowels: a o u y; in typography, in the absence of umlaut these letters are replaced by digraphs: ae oe ue which merely reflect a sound. In Germany, these forms have been deleted in the early 20th century by the umlaut. It is an archaic use that can still be found in some countries, i.e., USA, Canada! In France with the use of computers the umlaut, as well as the accent in capitals, have to be applied. Thus, one should write Schürch or SCHÜRCH not Schuerch, Wohlhüter or WOHLHÜTER not Wohlhueter - never Schurch or Wohlhuter. Consideration to our ancestors needs for us to correctly use given names and surnames… at least in genealogy!

The ligature or tied letter Œ/œ, called "e in the o", or Æ/ae, is Latin and does not exist in German. Thus, its use in German word is wrong: for ex. the village Röschwoog being written today officially Roeschwoog but Michelin and Wikipedia among others write Rœschwoog.

The origin of the name: the surname of a family has generally a single origin, often unrelated to the same surname of a neighbouring family, sometimes distant by only a few miles. Etymology and origin of the surnames were established in the 11-12th centuries: most of the surnames have mainly as origin: given names, geographical and topographical terms, nicknames, jobs. These observations confirm how much each family name is a special case that cannot be likened to a general case.

Finally, in a very general genealogical framework, we must never neglect the contribution - 50%! - brought by the spouse's surname, sometimes insolvable without this support more than complementary. In German and Swiss traditions, the name is attributed to a family to distinguish it from other families composing a social group: each spouse retains his surname. Some genealogists make this misunderstanding between the official and societal use that is obviously a mistake in genealogy.

The Given Names

Most of the Alsatian children have two given names: the first is often one commonly used for other family members (so-called name given by the family), and the second is specific to the child (Christian name), so considered as the usual one (Table 6). Remember that the names should be written as it appears in the birth record, using the language (German or French) of that act, i.e., without translation. In other records, such as marriage or death, only the usual names are often indicated for all the persons. Consequently, the data must be checked on the birth certificate to ensure the correct identity of the person. A partial identity (only the usual name) is often a source of error and confusion, especially in France where the first given name is the usual one.

Translation of a German given name to English or French often hampers the use within the family. Indeed, Johann, Johannes, Hans, Hanss ... can only be translated respectively to John and Jean. But in German, each of those cited given names is specific, distinct from the others, and can distinguish two members among siblings or cousins. This applies with other given names like Catharina, Kathrina, Catherina... Michel or Michael (no umlaut here!). Not knowing the local customs, or knowing them poorly, led to mistakes which were passed on. Another often overlooked point is the nickname for men: der Alte, der Mittere, der Junge. But that nickname changes over time because after the death of the "senior" (Alte), the "medium" (Mittlere) or "junior" (Junge) will be called Alte in an act. Then this nickname is not always passed from father to son or grandson, but sometimes to cousins. In all cases the surname of the spouse allows one to ascertain the identity. In some Alsatian genealogies established by American descendants, one labelled under John I, John II, John III, and the consequences on the validity of such an use can be seen on Table 6; in the same way to quote by an initial the second given name or by a nickname or alternative name in place of the complete or original given name does not fit with the basic rules in genealogy.

| |

from birth record |

usual given name |

US ranking |

| grandfather |

Johann Martin |

Martin |

John I |

| father |

Johann David |

David |

John II |

| son |

Johann Michael |

Michael |

John III |

|

| |

from birth record |

usual given name |

| grandmother |

Maria Catharina |

Catharina |

| mother |

Maria Margaretha |

Margaretha |

| spouse |

Anna Margaretha |

Margaretha |

|

Table 6. – Example of Alsatian specificity in the ranking of the given names over three generations.

Spouses keep their surname (see text).

In the Alsatian culture (German), tradition dictates that the given name(s) is indicated before the family name (surname). Here we apprehend the differences between Alsatian (German culture) and French (from Latin culture), and the historical gaps that often suggest that Alsace is French! Certainly it is today by nationality but not culture. In both customs, given name(s) and surname of the father and mother are needed in all records : in other words, a person keeps officially his surname all his life.

References and Links

Archives départementales du Bas-Rhin, online: parish & civil registers, census, emigration, cadastre... https://archives.bas-rhin.fr

Archives départementales du Haut-Rhin, online: parish & civil registers, census, emigration, cadastre... https://archives.haut-rhin.fr/search/home

Archives départementales du Territoire-de-Belfort, online: parish & civil registers, census, emigration, cadastre... https://archives.territoiredebelfort.fr/ - Nota : le Territoire de Belfort appartenait à l'Alsace jusqu'en 1871.

- voir aussi Association LISA http://www.lisa90.org/lisa1/pages1/accueil.html.

Duvignacq M. A., Marie Collin M. & E. Syssau (2011). Vous cherchez quelqu'un ? Archives et généalogie - Lire les actes. Archives départementales du Bas-Rhin, Strasbourg, 30 p.

Emig C. C., 2012. Alsace entre guerres et paix. In : Faire la guerre, faire la paix : approches sémantiques et ambiguïtés terminologiques. Actes des Congrès des Sociétés historiques et scientifiques, Éd. Comité des Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques, Paris, p. 195-207.

Emig C. C., 2014a. Quelques réflexions sur la Généalogie et sur son usage. Nouveaux eCrits scientifiques, NeCs_03-2014, 11p.

Emig C. C., 2014b. Généalogie Graber en Franche-Comté. Nouveaux eCrits scientifiques, NeCs_02-2014, p. 1-15.

Emig C. C., 2014. Alsace. http://emig.free.fr /ALSACE/index.html. Consulté le 20 juin 2021.

Geneafrance 2014. Recherches en Alsace. Consulté le 20 juin 2021.

Marthelot P., 1950. Les mennonites dans l'Est de la France. Revue de géographie alpine, 38 (3), 475-491.

Nègre X., 2014. Lexilogos. Dictionnaires alsaciens. . Consulté le 20 juin 2021.

Hug M., 2014. Orthographe de l'alsacien. http://elsasser.free.fr/OrthAls/. Consulté le 20 juin 2021.

Kasser-Freytag D., 2015. Manuel de paléographie alsacienne. Archives & Culture, Paris, Collection Guides de Généalogie, 160 p.

Prou M., 1924. Manuel de paléographie latine et française. Picard, Paris, 4e éd., 511 p.- pdf de l'édition 1890, 397 p.

Theleme. Dictionnaire des abréviations françaises, http://theleme.enc.sorbonne.fr/dico, consulté le 20 juin 2021.

Notes:

[1] An anecdote - one day, I got a message from a US cousin born Miller in Erie Co, NY, asking me for help in search for her ancestor, because she could not find him kowing birth date and location in Bas-Rhin. A bit surprised, I went directly to the register and found him under the surname Müller. Miller - Müller indeed, it's a sucker's history!

[2] In German, y is a vowel with the sound “ü” or “i”; in the latter case, it is often written with an umlaut: ÿ and can also be replaced by “i”.

The calendar change from Julian to Gregorian did not occur at the same time everywhere in Europe, that can still today cause confusion in genealogy with the dates, especially in the absence of religious sources.

Adopted by the Council of Trent (1542-1567), the replacement took place at the time of the religion wars. The refusal to adopt the new calendar was based primarily on politico-religious opposition to the papacy: primarily by the Protestant states, sometimes vehemently, and the Orthodox world as a whole. It spans over two centuries in Europe.

The conversion was made on the basis of a catch-up of 10 to 12 days (in 1582 the real difference was 12.7 days). Like many Catholic kingdoms (Italy, Spain, Portugal... on October 4, 1582), France adopted the Gregorian calendar on December 9, 1582. But, at that time, France was not within today's limits.

Great variations in time among Protestants, and sometimes also among Catholics states and parishes... over a period of more than two centuries! In genealogy, this may cause an interval in dates of the acts of about 10 days, especially if the source with the religion is not given.

Holy Empire

The Protestant Alsace, both possessions and parishes, as well as the possessions of the duchy of Württemberg in Franche-Comté, decided to apply the Gregorian calendar on January 5, 1682 [except Mulhouse on 1st January/12 January 1701, because part of the Swiss Confederation]. For example (Fig. 2): in the registers of Riquewihr, Duchy of Württemberg (no Catholic registers before 1685), the certificates between August and December 1681 bear the Julian/Gregorian dates, then from January 5, 1682 are following the Gregorian calendar.

Fig. 2 – Above, the death certificate of one of my ancestors Hanß David Binder [Sosa 2248 - G12], buried on 5/15 novembre 1681- see death register of Riquewihr city.

In the Duchy of Lorraine, the change occurred later on February 16, 1760, followed by February 28, 1760.

In Augsburg, a free Imperial city, belonging to the Imperial Swabian Circle (Schwäbischen Reichskreis), biconfessional since 1555, with a majority of Protestant population, the religious fronts were already particularly hardened. So when the majority of the city council voted for applying the Gregorian calendar in 1584 and also recruited troops, the situation came to a head. Evangelical preachers refused to adhere to the papal calendar; in the city on the brink of civil war, on June 3, 1584, they called to celebrate Ascension Day, which was imminent according to the old calendar. The council immediately banned this celebration and wanted to get rid of the loudest agitator Georg Müller and had him expelled out the city. The riot therefore broke out on July 4.

Subsequently, a tense calm returns to Augsburg. Then, during several years, the leaders were successful in implementing the new schedule to a possible conversion. Nevertheless, years later, while some Protestants used the new calendar, many celebrated church feasts according to the old one. Also, when the Swedish king Gustav Adolf conquered Augsburg in 1632, the city immediately reverted to the Julian era.

After the Thirty Years' War, around 1653, the prejudice among the Protestants was still persistent. In the letter of David Thomann von Hagelstein (1624-1688), a Lutheran cousin and evangelischer Ratskonsulent (= Stadtschreiber or alderman of the city council), the date is in Julian/Gregorian: 14/24 1674, confirming that the city did not still adopted the Gregorian calendar; I couldn't find the date. Note that Nuremberg, an Imperial free city, converted to Gregorian calendar in 1699.

Fig. 3. – Extract in facsimile from the bottom of p. 3, from a letter of 4 pages, closed by a seal, written in Augsburg by David Thomann.

Protestant Switzerland

Most of the Swiss reformed cantons, i.e., Basel, Bern, Geneva, Schaffhausen, Zürich, adopted the new calendar on January 1/January 12, 1701.

City of St. Gallen and the reformed part of the canton of Glarus in 1724 (the Catholic part in 1700).

Canton Appenzell on 14/25 December 1798.

Canton of the Grisons in 1812.

Appendix 1 mainly relates the change to the Gregorian calendar in the main countries and regions from which our ancestors originated. Knowing and studying the history and life of those are part of the studies for any genealogist, because they go beyond or must go far beyond the mere reading of certificates and registers, or worse the copy-paste of other pedigrees online.

In France, with the law on secularism (known as "loi sur la laïcité"), a French specificity or even exclusivity, religious affiliation is often returned to a hidden box, while more than half of the French registers are parish ones. However, the situation is quite distinct in the neighbour regions and countries of Germanic cultures (Alsace included).

The surname Schürch as example

En Alsace...

Since the 17th Century several families of Swiss Anabaptists (Täufer), namely Mennonites and Amish, have changed their surnames after emigration to Alsace and Montbéliard County and to Pennsylvania (USA). The variants may affect up to each child within the same family, so that each child can have a different surname derived from the father’s surname. On the contrary, mennonite families never changed their original surname after emigration, i.e., Graber, Roth, Amstutz... (Emig, 2014b).

Among the surname Schürch, none of the Anabaptist emigrants has retained the original name: Schürch. This surname was (and still is) borne by about 20 different families mainly from the Canton of Bern, Switzerland, unrelated with each other. From 1794, these variants were subject to French law – see above.

Variants used:

- Schirch, Schürch, Schirck: the 18th century in the County of Montbéliard.

- Churc, Chure, Churq, Churque, Schirch, Schurck, Schurque, Surcke, Surque, Schink, Schürk: in Belfort and the Sundgau (South of Alsace).

- Schurch, Schircker, Schirger: the 17th in the Sundgau near Muhlhouse.

- Cheric, Cherich, Cherique, Chirk, Gerig, Goerig, Kerique, Koerique, Scherich, Scherig, Scherik, Scherique, Schir, Schirch, Shirck, Schirk, Schirsch, Schoerich, SchoerSchurch, Schircher, Schirher: the 17th in the Bruche valley and surroundings (Alsace).

Such large variations are only found in Anabaptist families, while in Catholic or Protestant families, the changes, when any, are minor over one or two centuries for a given surname. This is also true in Catholic families named Schürch in Alsace, usually originating from the Catholic canton of Lucerne (Switzerland).

Research has been done to try to find an explanation but without success. Even descendants are unable to answer this point. In the records of the Doubs, Mennonite surnames are registered with the variant (that never happens in other surnames). Marthelot (1950) offers as explanation: “on a pu noter les déformations subies par les noms de famille mennonites, de consonance germanique, dans ces pays de langue romane.” (= it was noted the distortions suffered by the Mennonite surnames, of Germanic sounding in these countries of romance language). Actually, Mennonite families settled preferably in or near German-speaking localities, with the exception of Belfort and romance-speaking part of the Sundgau. Nevertheless, it is certain that the Anabaptists maintained the use of German and Schwyzerdutch, even in the USA, with a German dialect known as "Pennsylvania Dutch" (Pennsylvania German).

In America...

"There are about 62 different ways to write the name Schürch in North America," according to a statement made in the USA and Canada (Table 6.) but there are also two other variants in Alsace, not shown, i.e., Schicker and Schirger. "There are about 62 different ways to write the name Schürch in North America," according to a statement made in the USA and Canada (Table 6.) but there are also two other variants in Alsace, not shown, i.e., Schicker and Schirger.

Table 7. – Pictorial representation of all the American variants of the Swiss surname Schürch [presented at the Schürchtreffen 2010 SGNS - Schweizerische Gesellschaft der Namensträger Schürch).

[Enlarge]

Many of these surname bearers have no family relationships and never have had. There is here an amalgam leading to genealogical errors. For example, surnames, such as Schorch, Schörg, Schürg, Schurig which occur in France and Germany, are without any link with Switzerland. The correct surname of an emigrant from the Old World to the Americas should be certified by an official birth certificate, it is illusory to assign ancestry except to have fun with false ancestors.

→ US branches...

This multitude of variants in the US make it difficult to know the original surname. It is obviously surprising to emigrants so proud of their origin and in general of their surname. The reason of the patronymic changes was basically explained that: "When the Schürch from Switzerland settled in Pennsylvania, which was ruled by the British, German names were often changed by English-speaking officers who were not familiar with German names. Thus, some changes were observed because of letters absent from the English alphabet, like “ü”.” Nevertheless, the descendants of the Schürch from Sumiswald, arriving in Pennsylvania have chosen for variants Sherk, Shirk Sherick, Sherrick, or both within the same family! In Alsace the descendants of Valentin Schürch, emigrating from Sumiswald to Alsace, changed their surname to Schicker or Schirger over 3 generations. A cousin Schürch, reformed, who immigrated in the 19th century to the USA, kept his surname as Schuerch.

→ Canadian branches...

The first generation of the family of Joseph Sherk (1769-1853) (originally Joseph Schürch from Sumiswald), who emigrated to Canada (Waterloo Co, west of Toronto) was named Schoerg or Schörg. Then Joseph appears in the records of 1842 and 1851 under Sharick, while he, himself, signed "Joseph Shorg". Actually, he was known as that, in censuses, the census employee quoted the surname according to the pronunciation, not how it was spelled. One of the brothers of Joseph and his descendants was called Sherrich or Shirk. Joseph's son, Samuel, and his descendants (in Canada and in Michigan, USA) have been called Sherk. Another son Jacob kept the surname Sharick, but those of his descendants in Michigan have been called Shirk.

The similarity of the American variants with those observed in Alsace may suggest these latter, the oldest, were used as a model for US immigrants. The emigration route passed through Alsace until the North Sea.

Why the need for change patronymic...

I have in mind that the change had a deeper reason than only the "Americanization" of the name Schürch: a voluntary change linked to the consequences of a (leak) ? or forced exile of the native-country for political and religious beliefs. The debate is open, especially as the Swiss Schürch did not change their surname since the fourteenth century. In the same way, the other US branches of my Alsatian families of my grandparents: Wohlhüter, Sturm and Nadelhoffer all kept their surname without alteration.

Are Alsatian surnames Schirch, Schirck, Schirk, Schurck variants of Schürch?

Nothing is less certain, at least in Alsace. Because...

- Schirch and Schurck may be derived from the root "schirge" meaning in Alsatian push or drag. The nominee could have a strong opposition character. .

- Schirch is a Germanic form of the Christian name Georg, influenced by the slave language, and in the same meaning the surnames Schirach, Schira (k), Schiro (k), Schirck, Schirk.

However, there is no problem for variants the origin of which is established on records. But, on the contrary, without official evidence, a surname may not be considered as a variant of a surname. We may understand that genealogical searches have tendency to be emotional, in particular when no ascendant can be found. Genealogy has limits that are often difficult to get over. This might open the door to belief. On the other hand the solution may be found in the archives of the Alsatian locality or in the “Archives départementales” but is time-depending!

|