◄ Carnets Geol. 14 (15) ►

Contents

[1. Introduction] [2. Study area] [3. Material and methods]

[4. Paleontology]

[5. Distribution of ostracodes and paleoecology] [6. Paleogeography]

[7. Conclusions] and ... [Bibliographic references]

itt Fossil - Instituto Tecnológico de Micropaleontologia,

UNISINOS, Av. Unisinos, 950, São Leopoldo, RS (Brazil)

;

Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Ciências, Departamento de Geologia e Centro de Geologia, Campo Grande, C6, 4º, 1749-016 Lisboa (Portugal)

Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Ciências, Centro de Geologia, Campo Grande, C6, 4º, 1749-016 Lisboa (Portugal); deceased ( et al., 2013)

itt Fossil - Instituto Tecnológico de Micropaleontologia, UNISINOS, Av. Unisinos, 950, São Leopoldo, RS (Brazil)

itt Fossil - Instituto Tecnológico de Micropaleontologia, UNISINOS, Av. Unisinos, 950, São Leopoldo, RS (Brazil)

Published online in final form (pdf) on October 14, 2014

[Editor: Bruno ; language editor:

Robert W. ]

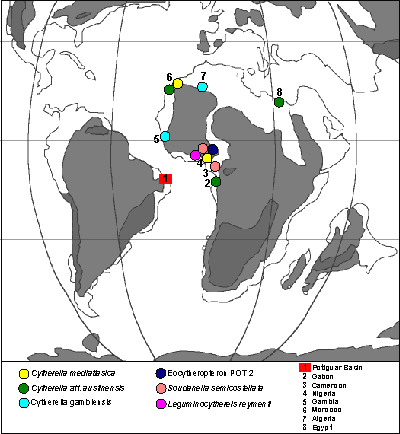

Sixty-four Ostracoda taxa were recorded from the Santonian–Campanian of Potiguar Basin, northeastern Brazil. The following new species were described: Triebelina anterotuberculata, Triebelina obliquocostata, Cophinia ovalis, Fossocytheridea potiguarensis, Ovocytheridea anterocompressa, Ovocytheridea triangularis, Perissocytheridea jandairensis, Semicytherura musacchioi and Protocosta babinoti. The faunal association indicates predominantly shallow marine environments, intercalated with typically mixohaline levels. These species are mostly endemic, although the presence of six species common to West and North Africa shows that migration was still possible by the end of the Cretaceous.

Ostracodes; Santonian–Campanian; Potiguar Basin; paleoecology; paleogeography.

E.K., M.C., J.-P., G. & C. (2014).- Ostracodes from the Upper Cretaceous deposits of the Potiguar Basin, northeastern Brazil: taxonomy, paleoecology and paleobiogeography. Part 2: Santonian-Campanian.- Carnets de Géologie [Notebooks on Geology], Brest, vol. 14, nº 15, p. 315-341.

Les ostracodes des sédiments du Crétacé supérieur du Bassin de Potiguar, NE Brésil : taxonomie, paléoécologie et paléobiogéographie. Deuxième partie : Santonian-Campanien.- 64 taxons d'ostracodes ont été recensés dans les sédiments de l'intervalle Santonien–Campanien du Bassin de Potiguar Basin, NE Brésil. De nouvelles espèces sont décrites ; il s'agit de Triebelina anterotuberculata, Triebelina obliquocostata, Cophinia ovalis, Fossocytheridea potiguarensis, Ovocytheridea anterocompressa, Ovocytheridea triangularis, Perissocytheridea jandairensis, Semicytherura musacchioi et Protocosta babinoti. L'association faunistique nous indique prédominamment des environnements marins peu profonds, présentant des intercalations de niveaux à faune typiquement mixohaline. Ces ostracodes sont pour la plupart des espèces endémiques, toutefois la présence de six espèces communes à l'Afrique de l'Ouest et du Nord montre que le phénomène migratoire était toujours possible vers la fin du Crétacé.

Ostracodes ; Santonien-Campanien ; Bassin de Potiguar ; paléoécologie ; paléobiogéographie.

This work follows up the study of the Upper Cretaceous ostracodes from Potiguar Basin, including the taxonomy, paleoecological and paleobiogeographical approaches. The first part ( et al., 2014) deals with the Turonian assemblages, whereas this work presents the study of the Santonian–Campanian assemblages.

Few studies on Upper Cretaceous ostracodes from the Northeast Brazilian margin have been published hitherto. For the Potiguar Basin two papers were published dealing exclusively with marine Upper Cretaceous ostracodes ( et al., 2000; et al., 2000). In contrast, the Sergipe Basin, contiguous to the study area, has been studied in more detail since the 60's (, 1964, 1966a, 1966b, 1967; , 1973a, 1979; et al., 2000). A more complete review of previous studies on marine ostracodes from the Upper Cretaceous of northeastern Brazil can be found in et al. (2014).

Studies from African basins, such as Gambia (, 1963), Algeria (, 1987), Morocco (, 1996), Nigeria (, 1960; , 1973a, 1973b; , 1987, 1992; , 1999a, 1999b), Egypt (, 2008), Gabon (, 1973a), and Cameroon (, 1951, 1962) revealed their importance as a source of data for taxonomy of the Potiguar Basin assemblages.

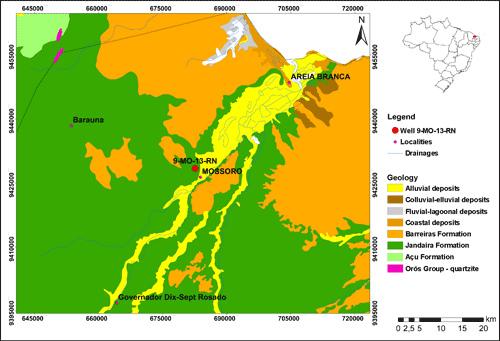

The Potiguar Basin is located at the intersection of the equatorial margin with the east continental margin, covering an area of approximately 48,000 km² between the Rio Grande do Norte and Ceará States (Fig. 1 ![]() ). Geologically, it is limited to the south, east and west by the crystalline basement, and extends north to the 2,000 m isobath (,

2003;

et al., 2007).

). Geologically, it is limited to the south, east and west by the crystalline basement, and extends north to the 2,000 m isobath (,

2003;

et al., 2007).

The Potiguar Basin originated from extensional stresses during the Early Cretaceous associated with rifting processes that culminated in the separation of the South American from the African plate. et al. (2007) divided the deposits in three supersequences: (i) rift, deposited in the Early Cretaceous (Berriasian–Lower Aptian), represented by fluvial-deltaic and lacustrine deposits of the Pendência and Pescada formations; (ii) post-rift, deposited during the Upper Aptian–Lower Albian and characterized by fluvial-deltaic deposits, with the first records of marine ingression (Alagamar Formation), and (iii) drift, comprising the entire marine sedimentation, from the Lower Albian to the Recent.

The Jandaíra Formation results from the first major marine ingression originally from the north (, 1976). This unit consists predominantly of bioclastic calcarenites and calcilutites deposited in tidal flat environments on a shallow platform ( & , 1988; & , 1994). & (1994), reviewing internal reports of Petrobras (the Brazilian oil company) attributed a Turonian–Campanian age to this formation, which was later corroborated by et al. (2007).

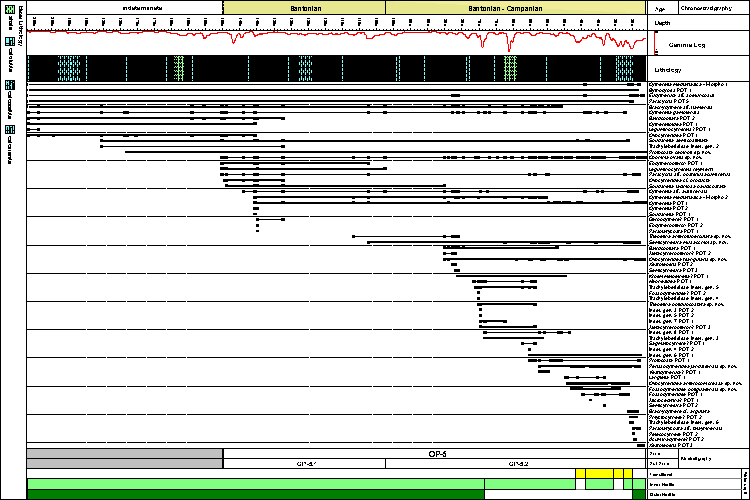

The Santonian was dated by the last occurrence of the planktonic foraminifers Dicarinella concavata and Whiteinella inornata. The base of Campanian is marked by the last occurrence of D. concavata and the top by the last occurrence of the palynomorph Auriculiidites reticulatus ( et al., 2000). The ostracode zone OP-5 (Santonian–Campanian) is marked by the presence of Ovocytheridea triangularis sp. nov. (= Ovocytheridea aff. O. producta et al., 2000) and Soudanella semicostellata (= Protobuntonia aff. P. semicostellata et al., 2000). The ostracode sub-zone OP-5.1 (Santonian) was identified by the range of Leguminocythereis reymenti (= Leguminocythereis aff. L. reymenti et al., 2000). The ostracode sub-zone OP-5.2 (Santonian–Campanian) is marked by the last occurrence of Leguminocythereis reymenti and the presence of Fossocytheridea potiguarensis sp. nov. (= Sarlatina sp. 1 et al., 2000).

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Figure 1: Potiguar Basin, showing the position of the studied well, 9-MO-13-RN, located in Mossoró city, Rio Grande do Norte State, Brazil (from Geological Survey of Brazil).

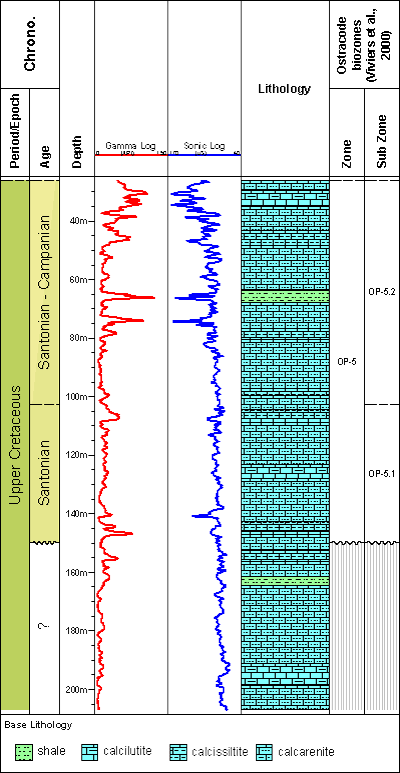

One hundred and seven samples were analyzed, covering 180 meters

from the well 9-MO-13-RN

(Fig. 2 ![]() ).

The samples averaged 60 g and are mainly represented by limestone intercalated with some levels of silt.

The samples were processed using the standard technique for fossil ostracodes, which consists of

disintegration with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), washing through

sieves with meshes of 250, 180 and 63 micrometers and dried at 60º C overnight. The selected specimens were imaged using a Zeiss EVO MA15 scanning electron microscope. Only Part

of the material was only illustrated

(Appendix 1) and includes the taxa undetermined

due to the scarcity, preservation, reduced stratigraphic value or even to the impossibility of inclusion

in any taxon described up to now.

).

The samples averaged 60 g and are mainly represented by limestone intercalated with some levels of silt.

The samples were processed using the standard technique for fossil ostracodes, which consists of

disintegration with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), washing through

sieves with meshes of 250, 180 and 63 micrometers and dried at 60º C overnight. The selected specimens were imaged using a Zeiss EVO MA15 scanning electron microscope. Only Part

of the material was only illustrated

(Appendix 1) and includes the taxa undetermined

due to the scarcity, preservation, reduced stratigraphic value or even to the impossibility of inclusion

in any taxon described up to now.

The map of the studied area was created using ArcGIS® software version 9.3 by ESRI (Environmental Systems Research Institute). The complete micropaleontological data were plotted using the StrataBugs® software, with well depth on the Y-axis and the identified taxa on the X-axis. The statistical data were calculated using the PAST software ( et al., 2001; & , 2006) and Microsoft Excel®.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Figure 2: Lithological profile and electrical logs of the studied interval of the well 9-MO-13-RN.

Taxonomy follows the classification of (2005). In the systematic descriptions, the following abbreviations/conventions are employed: L: length, H: height, W: width; very small (<0.400 mm), small (0.400-0.500 mm), medium (0.510-0.700 mm), large (0.710-0.900 mm), very large (>0.900 mm); C: carapace, RV: right valve, LV: left valve, DV: dorsal view, VV: ventral view, EV: external view (valve), IV: internal view; f: female, m: male. All dimensions are in mm. Type and figured specimens are deposited in the collections of Museu de História Geológica do Rio Grande do Sul, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, under the prefix ULVG followed by their respective catalogue numbers. All dimensions of the figured specimens are in the plate captions.

Class Ostracoda , 1802

Subclass Podocopa , 1866

Order Platycopida , 1866

Suborder Platycopina , 1866

Superfamily Cytherelloidea , 1866

Family Cytherellidae , 1866

Genus Cytherella , 1849

Cytherella gambiensis , 1963

(Pl. 1 ![]() ,

figs. A-D)

,

figs. A-D)

1963 Cytherella gambiensis , p. 1680, Pl. 1, figs. 1-3.

non 1981 Cytherella cf. gambiensis - et al., p. 221-222, Pl. 6, figs. 1-2.

1985 Cytherella cf. gambiensis - , p. 137-138, Pl. 1, fig. 7.

2000 Cytherella gambiensis - et al., p. 331-332, Figs. 8.3-8.4.

2000 Cytherella aff. C. gambiensis et al., p. 415, Figs. 8, 5-6 and 9-11.

Material: 286 specimens.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution: Turonian of Algeria (, 1985), Senonian of Gambia (, 1963), Upper Cretaceous of Potiguar Basin ( et al., 2000), Coniacian–Campanian ( et al., 2000) and Santonian–Campanian (this work) of Potiguar Basin.

Remarks: Despite the similarity, Cytherella paenovata , 1932, from the Upper Cretaceous of Texas, USA, has the maximum height at mid-length and has a small posterior projection. The species identified by (1964) as Cytherella aff. paenovata in the Cenomanian–Santonian of Egypt is significantly larger and has a less pronounced overlap. et al. (1981) identified Cytherella cf. gambiensis in the Turonian of Tunisia, but the 's species has a much more prominent overlap of the valves.

Cytherella mediatlasica , 1996

(Pl. 1 ![]() ,

figs. E-I)

,

figs. E-I)

1987 Cytherella sp. , p. 25, Pl. 13, figs. 5-6.

1992 Cytherella sp. , p. 328, Pl. 2, fig. 20.

1996 Cytherella mediatlasica , p. 484-485, 488, Pl. 1, figs. 1-10.

2000 Cytherella sp. P6 , , & , p. 415, fig. 8, 14-15.

Material: 182 specimens.

Brief description: Carapace large, sub-rectangular in lateral view, sub-rectangular to sub-oval in dorsal view. RV larger than the left one, with overlap along all margins, except in the posterior margin of the females. Dorsal margin of the RV almost straight, LV with a concavity in front of the mid-length; ventral margin slightly sinuous and subparallel to the dorsal margin. Maximum height in the posterior third. Anterior margin symmetrically rounded, posterior margin rounded to slightly truncated. Morphotype A: Surface punctated, with fine ribs parallel to the anterior margin. Morphotype B: Surface entirely and regularly punctated. Sexual dimorphism very pronounced, with females larger than males and presenting "brood-pouches".

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution: Turonian–Santonian of Nigeria (, 1987, 1992), Santonian of Morocco (, 1996), Turonian–Campanian of Potiguar Basin, Brazil ( et al., 2000; this work).

Remarks: The presence of different morphotypes in this species was observed by (1996) in the Santonian of Morocco. In the Turonian of this well ( et al., 2014) only specimens of the morphotype A were recorded.

Cytherella aff. austinensis , 1929

(Pl. 1 ![]() ,

figs. J-L)

,

figs. J-L)

aff. 1929 Cytherella austinensis , p. 51-52, Pl. 2, figs. 4, 6.

1973a Cytherella aff. austinensis - , p. 123-124, Pl. 2, fig. 1a-c.

1991 Cytherella sp. 1 , p. 441-442, Pl. 4, figs. 5-7.

2000 Cytherella austinensis - et al., p. 331, Figs. 8.1-8.2.

2008 Cytherella austinensis - et al., p. 539, Pl. 1, fig. 3.

Material: 765 specimens.

Brief description: carapace of medium size, oblong-oval in lateral view, lanceolate in dorsal view. RV larger than the left one, with overlap along all margins. Maximum height behind mid-length; maximum width in the posterior third. Dorsal margin almost straight to slightly convex; ventral margin convex in the females, straight in the males. Anterior margin broad and uniformly rounded; posterior margin lower and obliquely rounded. Surface smooth. Sexual dimorphism present, with males lower, narrower and more elongate than females.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution: Upper Cretaceous ( et al., 2000) and Santonian–Campanian (this work) of the Potiguar Basin, Brazil, Cenomanian of Morocco (, 1991) and of Gabon (, 1973a), Turonian–Santonian of Egypt ( et al., 2008).

Remarks: This species is similar to Cytherella austinensis , 1929, from the Cretaceous of Texas, USA, but has the maximum height in the posterior third, a different outline at the posterior margin and a small compression in dorsomedian region. The outline of this species is similar to Cytherella sp. 2 recorded by et al. (2009) in the Maastrichtian of the Pará-Maranhão Basin, Brazil. However, Cytherella sp. 2 et al., 2009, is slightly compressed along all margins and has an anteromarginal rim. Cytherella sergipensis , 1973, is significantly wider and the male specimens are more elongated than the species recorded herein.

Cytherella POT 1

(Pl. 1 ![]() ,

figs. M-P)

,

figs. M-P)

Material: 143 specimens.

Brief description: Carapace large, sub-oval in lateral view, very broad in dorsal view. Maximum height and maximum width slightly behind the mid-length. RV overlaps the left one along the entire periphery. Dorsal margin convex, ventral margin almost straight, with a slight concavity in the middle of the LV. Anterior and posterior margins rounded. Surface smooth.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: The carapace of this species is significantly less robust and the overlap is less pronounced than in Cytherella gambiensis (see above). This species is similar to Cytherella gr. ovata (, 1841) which has been recorded in the Cretaceous of many countries in America, Asia, Africa and Europe. Some of these records are similar to the species recorded in this study (e.g., & , 1974; et al., 1985; , 1985; , 1989; , 1991). However, the Brazilian species differs from C. ovata figured by the cited authors especially in the posterior region, which is more rounded.

Genus Cytherelloidea , 1929

Cytherelloidea POT 1

(Pl. 1 ![]() ,

figs. Q-R)

,

figs. Q-R)

Material: 4 specimens.

Brief description: Carapace of medium size, sub-rectangular in lateral and dorsal views. RV larger than the left one. Greatest height at anterior third, maximum width in the posterior region. Dorsal margin nearly straight, with the left valve with a concavity in the anterior third; ventral margin straight. Anterior margin rounded, posterior margin obliquely rounded, slightly projecting upward. Carapace surface with strong ribs: a marginal rib, along all margins and two central ribs, C-shaped, one in the median-dorsal region and another in the ventral region.

Age: Santonian.

Remarks: This species is similar to Cytherelloidea sp. P1 et al., 2000, recorded in the Coniacian–Lower Campanian of Potiguar Basin, but has a more rounded outline and the posterior margin projected downwards.

Order Podocopida , 1866

Suborder Bairdiocopina , 1887

Superfamily Bairdioidea , 1887

Family Bairdiidae , 1887

Genus Bairdoppilata , & , 1935

Bairdoppilata POT 1

(Pl. 2 ![]() ,

figs. A-C)

,

figs. A-C)

Material: 50 specimens.

Brief description: carapace large, very robust, sub-trapezoidal in lateral view, inflated in dorsal view. Overlap on the RV very pronounced, more developed in the dorsal and ventral margins. Maximum height at mid-length, maximum width slightly in front of the mid-length. Dorsal margin almost straight in the RV and convex in the LV; ventral margin convex. Anterior and posterior margins asymmetrically rounded. Surface punctated in the anterior and posterior parts.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Genus Neonesidea , 1969

Neonesidea POT 1

(Pl. 2 ![]() ,

figs. D-G)

,

figs. D-G)

Material: 61 specimens.

Brief description: carapace large, ovate to sub-rhomboidal in lateral view, inflated in dorsal view. LV overlaps the right one along the dorsal and ventral margins. Maximum height at anterior cardinal angle, maximum width slightly in front of the mid-length. Dorsal margin of the RV straight, slightly convex in the LV; ventral margin of the LV straight, sinuous in the RV. Anterior and posterior margins asymmetrically rounded. The carapace has a compression in the anterior, anteroventral and posteroventral regions. Surface smooth.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: Although the differentiation between the Bairdiidae genera is mainly based on appendages and internal carapace morphology, this species is assigned to Neonesidea due to the absence of any posterodorsal concavity or pronounced ventral sinuation, which are diagnostic external characteristics of Bairdoppilata.

Genus Triebelina , 1946

Triebelina anterotuberculata , & sp. nov.

(Pl. 2 ![]() ,

figs. H-L)

,

figs. H-L)

Derivatio nominis: After the presence of a marked tubercle in the anterior region.

Material: 65 specimens.

Holotype: C, ULVG-9860 (Pl. 2, fig. H), sample 111.80 m.

Paratypes: ULVG-9859, ULVG-9860.

Dimensions: Holotype: L: 0.940, H: 0.505, W: 0.409.

Paratypes: L: 0.744-0.860, H: 0.416-0.478, W: 0.310-0.360.

Type-locality: 9-MO-13-RN, coordinates UTM: 682595E / 9428410N (zone 24S), 111.80 m, Potiguar Basin, Brazil.

Diagnosis: A species of the genus Triebelina characterized by a very large, sub-trapezoidal and moderately calcified carapace. Surface punctated, with an anterior tubercle in both valves and a developed concavity in the ventral margin of the RV.

Description: carapace very large, sub-trapezoidal in lateral view, sub-rectangular and narrow in dorsal view. Overlap of the LV on the RV slightly and uniformly developed, except in the anterior and posterior regions, where it is not present. Greatest height at anterior cardinal angle. Maximum width at mid-length. Dorsal margin almost straight, ventral margin with a concavity in the mid-length of the RV, almost straight in the LV. Surface densely punctated. Presence of a sharp tubercle in the anterior region, above the mid-height, in both valves. Anterior and posterior regions with a slight compression. Internal features not observed.

Sexual dimorphism: not observed.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: Triebelina keiji & , 1978, from Cenomanian–Turonian of Portugal is very similar to the Brazilian species, but has two anterior tubercles and the posterior region is more projected and compressed.

Triebelina obliquocostata , & sp. nov.

(Pl. 2 ![]() ,

figs. M-P)

,

figs. M-P)

Derivatio nominis: After the developed oblique rib which ornates the lateral surface of this species.

Material: 6 specimens.

Holotype: C, ULVG-9869 (Pl. 2, figs. M-O), sample 74.40 m.

Paratype: ULVG-9870.

Dimensions: Holotype: L: 0.651, H: 0.378, W: 0.411.

Paratype: L: 0.704, H: 0.400, W: 0.432.

Type-locality: 9-MO-13-RN, coordinates UTM: 682595E / 9428410N (zone 24S), 74.40 m, Potiguar Basin, Brazil.

Diagnosis: A species of the genus Triebelina characterized by a large and robust carapace, sub-rhomboidal in lateral view, ventrally flattened. Surface reticulated and with a strong oblique rib, running from the anterior to the posterior region.

Description: carapace large, very robust, sub-rhomboidal in lateral view, inflated in dorsal view, with almost parallel margins. Overlap of the LV on the right one along all margins, except in the anterior one. Maximum height at anterior cardinal angle, maximum width at mid-length. Dorsal margin straight; ventral margin of the LV straight, with a concavity in front of the mid-length in the RV. Anterior and posterior margins asymmetrically rounded. Ventral region strongly flattened. The carapace has a compression in the anterior and posteroventral regions. Surface reticulated and with a strong rib which extends from the anterior region descending to the posterior one. Internal features not observed.

Sexual dimorphism: not observed.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: Despite of the few specimens recovered, this species has marked features that differentiate it from the known species of the genus Triebelina. A similar ornamentation pattern was observed in Triebelina boldi , 1955, recorded in the Miocene of SW France, but the species differs strongly in the outline.

Suborder Cypridocopina , 1850

Superfamily Cypridoidea , 1845

Family Candonidae , 1900

Subfamily Paracypridinae , 1923

Genus Paracypris , 1866

Paracypris aff. posteriusacuminatus , 1996

(Pl. 3 ![]() , figs.

A-C)

, figs.

A-C)

aff. 1996 Paracypris posteriusacuminatus , p. 489, Pl. 2,figs. 6-12.

2000 Paracypris sp. 1 , & , p. 334, Figs. 8.8-8.10.

Material: 114 specimens.

Brief description: Carapace large, elongated and sub-triangular in lateral view, sub-oval elongated in dorsal view. Greatest height slightly behind the mid-length, greatest width at mid-length. Overlap of the RV along all margins being less pronounced in the ventral one. Dorsal margin convex, ventral margin almost straight. Anterior margin obliquely rounded, posterior margin acuminate. Posterodorsal region angulated. Surface smooth.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution: Upper Cretaceous of Potiguar Basin ( et al., 2000) and Santonian–Campanian (this work).

Remarks: Despite the similarity, P. posteriusacuminatus , 1996, from the Santonian of Morocco, has the posterior cardinal angle less marked and is shorter, wider and more elongated.

Suborder Cytherocopina , 1850

Superfamily Cytheroidea , 1850

Family Cytherideidae , 1925

Genus Cophinia , 1961

Cophinia ovalis , & sp. nov.

(Pl. 3 ![]() , figs.

D-I)

, figs.

D-I)

2000 Cophinia aff. C. apiformis , , & , p. 423, Fig. 13, 1-4.

Derivatio nominis: After its ovoid lateral and dorsal outlines.

Material: 449 specimens.

Holotype: C, f, ULVG- 10389 (Pl. 1, fig. D), sample 30.40 m.

Paratypes: ULVG-10384, ULVG-10390, ULVG-10226, ULVG-10302.

Dimensions: holotype: L: 0.960, H: 0.700, W: 0.560.

Paratypes: L: 0.840-0.920, H: 0.580-0.649, W: 0.440-0.500.

Type-locality: 9-MO-13-RN, coordinates UTM: 682595E / 9428410N (zone 24S), 30.40 m, Potiguar Basin, Brazil.

Diagnosis: A species of Cophinia characterized by an ovoid and heavily calcified carapace, with a pronounced posterior projection near the mid-height.

Description: carapace very large, thick, ovoid in lateral and dorsal views. Left valve larger than the right one, along all margins though less pronounced in the anterior margin. Maximum height and maximum width at mid-length. Dorsal margin strongly convex, ventral margin convex with a small concavity in the anterior half of the right valve. Anterior margin obliquely rounded, posterior margin with a distinct projection of both valves, located around mid-height giving the carapace its typical appearance. Surface smooth. Merodont hinge.

Sexual dimorphism: pronounced, with females higher, more inflated and less elongated than males.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: This species differs from Cophinia apiformis (, 1960), from the Coniacian–Lower Santonian of Nigeria, mainly in the much more oval outline and in the ventral margin, which is more convex. Moreover, in C. apiformis, the posterior projection is more developed in the LV and less developed in the RV. Cophinia ovata , 1963 (Senonian, Senegal), has a deep anterodorsal sulcus observed in lateral and dorsal views and the posterior projection less pronounced. In dorsal view, this species is similar to Ovocytheridea acuta , 1963, from the Senonian of Gambia, but, in lateral view, O. acuta displays a downward projection in the RV, differing from the Brazilian species. O. acuta is probably a species of Cophinia.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution: Santonian–Campanian, Potiguar Basin, Brazil ( et al., 2000; this work).

Genus Fossocytheridea & , 1964

Fossocytheridea potiguarensis , & sp. nov.

(Pl. 3 ![]() , figs.

J-P)

, figs.

J-P)

2000 Sarlatina sp. P5 , , & , p. 424, Fig. 14, 5-8.

Derivatio nominis: After the Potiguar Basin, where this species was found.

Material: 600 specimens.

Holotype: C, f, ULVG-10181 (Pl. 1, fig. J), sample 33.80 m.

Paratypes: ULVG-10195, ULVG-10184, ULVG-10187, ULVG-10169, ULVG-10186, ULVG-10177.

Dimensions: holotype: L: 1.060, H: 0.640, W: 0.540.

Paratypes: L: 0.920-1.220, H: 0.540-0.660, W: 0.460-0.520.

Type-locality: 9-MO-13-RN, coordinates UTM: 682595E / 9428410N (zone 24S), 33.80 m, Potiguar Basin, Brazil.

Diagnosis: A species of Fossocytheridea characterized by a very large carapace, with an oblique and shallow anterodorsal sulcal depression and a slightly compressed anterior margin.

Description: carapace very large, heavily calcified, sub-rectangular in lateral view, sub-ovate in dorsal view. Anterior and posterior cardinal angles weakly developed. The left valve overlaps the right one along all margins, less pronounced dorsomedially and posteroventrally. Greatest height near the mid-length. Anterior and posterior margins obliquely rounded. Dorsal margin almost straight, truncated along its posterior slope. Ventral margin nearly straight, anteriorly sinuous. The density of the normal pores is low. The pores are large and distributed over the whole surface of the valves. The anterodorsal sulcal depression is shallow and obliquely inclined towards the anteroventral margin. Anterior region slightly compressed. Antimerodont hinge, LV with an elongated crenulated anterior socket, crenulated bar and a smaller posterior crenulated socket.

Sexual dimorphism: pronounced, females higher in the posterior third, shorter, more inflated and with a more convex ventral margin than males; in dorsal view the greatest width is located more posteriorly.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution: Santonian–Campanian of Potiguar Basin, Brazil ( et al., 2000; this work).

Remarks: Fossocytheridea lenoirensis & , 1964 (Albian–Lower Cenomanian, North Carolina, USA), differs from this species in possessing a more acute posterior margin, especially in the RV and a deeper anterodorsal sulcal depression. Fossocytheridea kirklandi , , & , 2003 (Cenomanian, Utah, USA) can be distinguished by its shorter length, more flattened anterior margin and presence of ocular swelling. Fossocytheridea maliensis (, & , 1996), recorded in the Campanian –Late Maastrichtian of Mali, has a reniform shape, with the dorsal margin more convex and a more pyriform outline in dorsal view.

Fossocytheridea POT 1

(Pl. 4 ![]() , figs.

A-D)

, figs.

A-D)

Material: 84 specimens.

Brief description: carapace of medium size, sub-rectangular to sub-triangularin lateral view, sub-oval in dorsal view. Overlap of the LV on the RV along all margins, less pronounced in the anterior margin. Maximum height at anterior cardinal angle. Greatest width at anterior third. Anterior and posterior margins asymmetrically rounded. Dorsal and ventral margins almost straight. Anterior cardinal angle well developed. Surface strongly reticulated, with smaller reticula near the anterior and posterior regions. Deep and long median sulcal depression. In dorsal view, the valves are almost parallel, with a marked median sulcal depression. Internal view not observed. Sexual dimorphism observed, with females more sub-triangular, wider and shorter than males.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: Although reticulate species of Fossocytheridea are not common, variable patterns of reticulation are possible, as proposed by et al. (2003) in the emended diagnosis of the genus.

Fossocytheridea? POT 2

(Pl. 4 ![]() , figs.

E-H)

, figs.

E-H)

Material: 92 specimens.

Brief description: carapace large, heavily calcified, sub-rectangular in lateral view, ovoid in dorsal view. Maximum height at anterior cardinal angle, maximum width before the mid-length. Overlap of the RV along all margins, more pronounced in the dorsal margin. Anterior and posterior margin obliquely rounded. Dorsal margin almost straight, with well marked cardinal angles; ventral margin slightly convex in the LV and nearly straight in the RV. Anterodorsal sulcal depression very shallow. Surface smooth.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: The precise identification at genus level of this specie is still under study due to the poor development of the anterodorsal sulcal depression.

Genus Ovocytheridea , 1951

Ovocytheridea anterocompressa , & sp. nov.

(Pl. 4 ![]() , figs.

I-M)

, figs.

I-M)

Derivatio nominis: After the compression in the anterior zone.

Material: 1943 specimens.

Holotype: C, f, ULVG-10283 (Pl. 4, figs. I-K), sample 47.60 m.

Paratypes: ULVG-10237, ULVG-10160.

Dimensions: holotype: L: 0.840, H: 0.520, W: 0.400.

Paratypes: L: 0.700-0.780, H: 0.420-0.460, W: 0.320.

Type-locality: 9-MO-13-RN, coordinates UTM: 682595E / 9428410N (zone 24S), 47.60 m, Potiguar Basin, Brazil.

Diagnosis: A species of Ovocytheridea with a sub-rectangular to sub-triangular carapace, with a shallow median sulcus and an anterior region compressed.

Description: carapace large, sub-rectangular to sub-triangular in lateral view, sub-oval elongated in dorsal view. LV overlaps RV along entire margin, less pronounced in the anterior region. Greatest height before mid-length, greatest width just in front of the mid-length. Anterior margin asymmetrically rounded, posterior margin strongly truncated and slightly projected downwards in the RV. Dorsal margin convex, ventral margin almost straight in the LV valve, slightly concave in the RV. Anterior region compressed. Surface smooth. Presence of a sulcus in the middle of the carapace and of another sulcus, very subtle, in the anterodorsal region. Hinge of the LV with an anterior large and crenulated socket and a crenulated bar; posterior element not preserved.

Sexual dimorphism: observed, females higher and shorter than males.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: this species is less triangular and lower than Ovocytheridea sp. aff. producta , 1962, recorded in this study. It differs from O. triangularis sp. nov. (this work) by the less developed anterodorsal sulcus.

Ovocytheridea triangularis , & sp. nov.

(Pl. 4 ![]() , figs.

N-R)

, figs.

N-R)

2000 Ovocytheridea aff. O. producta , 1962 - et al., p. 423, Fig. 13, 21-22.

Derivatio nominis: From the general aspect of the carapace.

Material: 261 specimens.

Holotype: C, f, ULVG-10112 (Pl. 1, fig. N), sample 27.90 m.

Paratypes: ULVG-10119, ULVG-10090, ULVG-10075, ULVG-10149.

Dimensions: holotype: L: 0.880, H: 0.600, W: 0.440.

Paratypes: L: 0.800-0.900, H: 0.480-0.600, W: 0.380-0.460.

Type-locality: 9-MO-13-RN, coordinates UTM: 682595E / 9428410N (zone 24S), 27.90 m, Potiguar Basin, Brazil.

Diagnosis: Sub-triangular and heavily calcified species of Ovocytheridea with a deep anterodorsal sulcus.

Description: carapace large, sub-rectangular to sub-triangular in lateral view, ovoid in dorsal view. LV overlaps the RV along entire margin, more pronounced in the dorsal and ventral margins. Greatest height and width at mid-length on females; in the males the greatest height is at anterior cardinal angle. Anterior margin asymmetrically rounded, posterior margin slightly truncated. Dorsal and ventral margins of the LV convex. In the RV, dorsal margin almost straight, with both cardinal angles well marked; ventral margin sinuous. Anterior region slightly compressed. Surface covered by punctations which are larger in the central part of the carapace and decrease in size towards the periphery. In the anterodorsal region there is a deep and oblique sulcus. In the posteroventral margin of the RV a small protuberance is present, especially in the males. Hinge of the LV with a short anterior crenulated socket, a crenulated bar and a posterior crenulated socket. The anterior and posterior sockets are almost of the same size.

Sexual dimorphism: observed, females higher and wider than males.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution: Santonian–Campanian, Potiguar Basin, Brazil ( et al., 2000; this work).

Remarks: This species is similar to Ovocytheria brevis , 1962, first recorded in the Lower Senonian of Algeria, but the Brazilian species is more elongated, has the anterodorsal sulcus more pronounced and less developed dorsal overlap of the RV. Ovocytheridea brevis (Pl. VII, figs. 6-8) recorded by et al. (1973) in the Coniacian of Algeria has an anterodorsal sulcus similar to this species; however it is higher and has the ventral margin straighter than the Brazilian one. Ovocytheridea cf. brevis, from the Coniacian of Algeria, figured by (1985) shows the anterodorsal sulcus very pronounced as seen in the Brazilian species and also a more pronounced dorsal overlap of the RV. Besides the similarity in external lateral view shape (presence of post-ocular sulcus and punctated surface) with the genus Schuleridea & , 1946, the hinge is different and consistent with the proposal into the genus Ovocytheridea.

Ovocytheridea cf. producta , 1962

(Pl. 5 ![]() , figs.

A-D)

, figs.

A-D)

cf. 1962 Ovocytheridea producta , p. 118-120, Pl. 1, figs. 9-17; Pl. 2, figs. 24-27.

non 2000 Ovocytheridea aff. O. producta - et al., p. 423, Fig. 13, 21-22.

Material: 49 specimens.

Brief description: carapace large, sub-rectangular to sub-triangular in lateral view, ovoid and inflated in dorsal view. Inequivalve, with the left valve overlapping the right one along the entire periphery, more conspicuous in dorsal and posterior margins. Anterior margin asymmetrically rounded, posterior margin truncated. Dorsal margin convex, ventral margin straight to slightly sinuous. Posteroventral region with a small compressed projection in the RV. Maximum height at mid-length; greatest width near the mid-length of the carapace. Surface scarcely punctate. Internal view: absence of vestibule, anterior marginal pore canals irregular and numerous (more than 20); muscle scars: 4 elongated and rounded, arranged in a vertical row, frontal scar V-shaped and a possible rounded mandibular scar.

Sexual dimorphism: females shorter and higher than males.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: This species is very similar to O. producta , 1962, from the Coniacian of Cameroon, but in this species, in dorsal view, both anterior and posterior extremities are more symmetrical. It differs from Ovocytheridea nuda , 1951, from the Campanian of Cameroon, in the less sub-triangular outline and in the posteroventral margin which has a small projection in the RV.

Genus Perissocytheridea , 1938

Perissocytheridea jandairensis , & sp. nov.

(Pl. 5 ![]() , figs.

E-I)

, figs.

E-I)

2000 Semicytherura sp. P1 , , & , p. 424, Fig. 14, 19-23.

Derivatio nominis: After the Jandaíra Formation, where this species was found.

Material: 478 specimens.

Holotype: C, f, ULVG-10193 (Pl. 5, fig. E), sample 34.00 m.

Paratypes: ULVG-10259, ULVG-10179, ULVG-10260, ULVG-10078.

Dimensions: holotype: L: 0.540, H: 0.280, W: 0.380.

Paratypes: L: 0.420-0.610, H: 0.220-0.280, W: 0.220-0.340.

Type-locality: 9-MO-13-RN, coordinates UTM: 682595E / 9428410N (zone 24S), 34.00 m, Potiguar Basin, Brazil.

Diagnosis: A species of Perissocytheridea characterized by a sub-rectangular to sub-trapezoid carapace, surface with longitudinal striations and heavily reticulated, presence of a very deep anterodorsal sulcus and an acuminate posterior margin.

Description: carapace of medium size, sub-rectangular to sub-trapezoid in lateral view, sub-oval, with a marked median sulcus in dorsal view. The valves are almost of the same size, with small overlap of the RV by the LV. Greatest height at anterior cardinal angle, greatest width behind the mid-length. Posterior region compressed. Dorsal margin nearly straight, ventral margin straight to slightly convex. Anterior margin broadly rounded, posterior margin acuminate, with the extremity situated in the lower third of the height. Ventrolateral expansion in the ventral region more pronounced in the males. Carapace strongly reticulated, with ribs parallel to the outline near the margins and, except in the ocular region, longitudinal ribs in the centre. Anterodorsal sulcus well developed. Eye tubercle present. Antimerodont hinge with all elements strongly crenulated.

Sexual dimorphism: the females are shorter and wider than males. The posterior projection is located slightly below the mid-height in the females and in the lower third in the males.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution: Santonian–Campanian, Potiguar Basin, Brazil ( et al., 2000; this work).

Remarks: et al. (2000) proposed that this species is a representative of the genus Semicytherura , 1957. Semicytherura has a caudal process situated subcentrally to subdorsally and the valves often have wing-like lateral prolongations. In our species the caudal process is not present. Perissocytheridea jandairensis sp. nov. differs from Metacytheropteron GA C 24 , 1979, recorded in the Cenomanian–Turonian of Gabon (probably a Perissocytheridea species) mainly in the more pronounced posterior extremity and the less convex dorsal margin.

Family Cytheruridae , 1894

Genus Eocytheropteron , 1933

Eocytheropteron POT 1

(Pl. 5 ![]() , figs.

J-L)

, figs.

J-L)

Material: 65 specimens.

Brief description: carapace of medium size, sub-oval in lateral and dorsal views. LV larger than the right one, with overlap more pronounced in the dorsal margin. Greatest height in the anteromedian region, greatest width at mid-length. Dorsal margin almost straight to slightly convex; ventral margin convex, partially hidden by the ventrolateral expansion, especially in the females. Anterior margin obliquely rounded, posterior margin triangular and projected upwards, with a narrow and short caudal process. Surface entirely covered by weak and small reticulation. Sexual dimorphism pronounced, with males longer and lower than females.

Age: Santonian.

Eocytheropteron POT 2

(Pl. 5 ![]() , figs.

M-N)

, figs.

M-N)

1999a Cytheropteron sp. , p. 92, Figs. 6.14-6.15.

2000 Eocytheropteron sp. P3 , , & , p. 426, Fig. 15, 10-11.

Material: 1 specimen.

Brief description: carapace of medium size, sub-rectangular to sub-ovoid in lateral view, inflated in dorsal view. LV larger than the RV, with a strong overlap in the dorsal margin. Greatest height and width at mid-length. Dorsal margin nearly straight to slightly convex, ventral margin convex, partially hidden by the pronounced ventrolateral expansion. Anterior margin sub-rounded, posterior triangular with a very developed caudal process in the upper third of the height. Surface strongly reticulated. Ventral region with parallel ribs.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution: Turonian–Coniacian of Nigeria (, 1999a), Santonian–Campanian, Potiguar Basin, Brazil ( et al., 2000; this work).

Remarks: Though only one carapace was recovered in the studied material, there is no doubt about its generic assignment. According to (1933) Eocytheropteron differs from Cytheropteron , 1865, in being ventrally inflated, lacking a wing-like lateral expansion, and usually having a distinctly larger LV which overlaps the RV conspicuously along the dorsal margin. The species Eocytheropteron anteretroversicardinatum , 1991, recorded in the Aptian–Lower Turonian of Morocco is similar, but has a much more convex dorsal margin and a less developed ventrolateral expansion. The outline of "Cytheropteron sp." , 1960, from Turonian strata from Nigeria (, 1973b) and Coniacian of Nigeria (, 1960) is similar but the specimens are more convex in dorsal margin and have a well developed median rib, not present in the material recorded in the Potiguar Basin.

Genus Semicytherura , 1957

Semicytherura musacchioi , & sp. nov.

(Pl. 5 ![]() , figs.

O-S)

, figs.

O-S)

Derivatio nominis: In honor of the late Argentinian micropaleontologist Dr. Eduardo , for his important contribution to the study of ostracodes.

Material: 69 specimens.

Holotype: C, ULVG-10089 (Pl. 5, figs. O-P), sample 27.60 m.

Paratypes: ULVG-9921, ULVG-10098.

Dimensions: holotype: L: 0.370, H: 0.180, W: 0.160.

Paratypes: L: 0.314-0.350, H: 0.152-0.170, W: 0.143-0.152.

Type-locality: 9-MO-13-RN, coordinates UTM: 682595E / 9428410N (zone 24S), 27.60 m, Potiguar Basin, Brazil.

Diagnosis: A species of Semicytherura characterized by the very small and sub-rectangular carapace, maximum width in the anterior third, ventral margin slightly concave, surface with large reticula and deep post-ocular sulcus.

Description: carapace very small, sub-rectangular and elongate in lateral view, nearly lanceolate in dorsal view. Valves almost of the same size, with the LV overlapping the left one dorsally. Maximum width at anterior third. Dorsal margin almost straight, ventral margin with a small concavity in the mid-length. Anterior margin nearly straight, posterior margin triangular, with a caudal process slightly above the mid-height. Anterior region compressed. Surface with larger reticula. Eye tubercle pronounced. Post-ocular sulcus deep. Internal features not observed.

Sexual dimorphism: females more inflated than males.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: The differentiation between the genera Cytherura , 1866, and Semicytherura , 1957, is based on differences in the hinge, marginal zone and marginal pore canals. We sustain the generic status of this species based on the ornamentation pattern. According to & (2010), Semicytherura varies considerably in shape, outline and ornamentation, from smooth to strongly costate, from punctate to tuberculate. Species of Cytherura, on the other hand, are all rather similar in shape and ornament and have smooth to punctate or delicately reticulate carapace ornament.

Semicytherura POT 1

(Pl. 6 ![]() , figs.

A-B)

, figs.

A-B)

Material: 16 specimens.

Brief description: carapace very small, sub-rectangular in lateral view, sub-oval and narrow in dorsal view. LV overlaps the RV in the posterodorsal margin. Maximum width in the posterior third. Dorsal margin almost straight and with a subtle concavity at mid-length; ventral margin straight. Anterior margin nearly straight, posterior margin triangular, with caudal process slightly above the mid-height. Surface entirely covered by weak and large reticula, with dense and very small secondary reticulation. Eye tubercle and post-ocular sulcus present.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: Besides the similarity in the general lateral outline, this species differs from Semicytherura musacchioi sp. nov. in the ornamentation pattern and in the location of the maximum width, which is in the posterior third.

Semicytherura POT 2

(Pl. 6 ![]() , figs.

C-D)

, figs.

C-D)

Material: 5 specimens.

Description: carapace very small, sub-rectangular in lateral view, inflated in dorsal view. Valves nearly equal. Maximum height at the anterior cardinal angle; maximum width in the posterior third. Dorsal margin straight, ventral margin almost straight, with a concavity at mid-length. Anterior margin asymmetrically rounded, posterior margin triangular. Caudal process acuminate, situated in the upper third of the height. Surface ornamented by strong ribs. The ventral and dorsal ribs are parallel to the contiguous margins. In the anterior region there is a rib Y-shaped, connected to the ventral rib. In the middle of carapace the ribs are sinuous. Eye tubercle small.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: This species differs from the others identified in the Potiguar Basin by the strong ribs and the position of the caudal process.

Genus Vesticytherura , 1964

Vesticytherura? POT 1

(Pl. 6 ![]() , figs.

E-G)

, figs.

E-G)

Material: 26 specimens.

Brief description: carapace very small, sub-rectangular in lateral and dorsal views. Valves nearly equal. Maximum height in front of the mid-length; maximum width at the posterior third. Dorsal margin straight, ventral margin convex. Anterior and posterior margins asymmetrically rounded, with the posterior one projected upwards. Presence of a strong and sinuous median rib, which develops three upturned curves (anterior, median and posterior) towards the dorsal region, defining two sulci in the dorsal region. Prominent eye tubercle. Sexual dimorphism present: males lower and more elongated than females.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: The genus Vesticytherura , 1964, was proposed to include species firstly belonging to Eucytherura, but with differences in pore canals number and in developed sulci on the external surface. Besides the absence of internal features, which were not observed, the external lateral and dorsal views and the other external characteristics of the Brazilian species are in accordance to the Vesticytherura diagnosis.

Family Trachyleberididae , 1948

Genus Langiella , , & , 2005

Langiella POT 1

(Pl. 6 ![]() , figs.

H-J)

, figs.

H-J)

Material: 12 specimens.

Brief description: carapace large, sub-rectangular in lateral view, sub-oval with the extremities very compressed in dorsal view. LV slightly overlaps the right one. Maximum height at anterior cardinal angle; maximum width in front of the mid-length. Dorsal margin almost straight sloping slightly posteriorly; ventral margin almost straight and subparallel to the dorsal margin. Anterior margin rounded, posterior margin rounded to sub-triangular. Surface reticulate, with reticula larger in the anterior region and absent in the posterior region. Presence of a weak dorsal rib and a strong ventral one, short and curved. Anteromarginal rib developed. Eye tubercle small. Internal features not observed. Sexual dimorphism probably present, with females more rounded and shorter.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: This species differs from Langiella reymenti , , & , 2005 (Danian, Pernambuco-Paraíba Basin, Brazil) in the posterior margin, which is less rounded, without spines and in the ornamentation pattern, predominantly reticulated.

Genus Protocosta , 1969

Protocosta babinoti , & sp. nov.

(Pl. 6 ![]() , figs.

K-P)

, figs.

K-P)

2000 Cythereis? sp. P8 , , & , p. 433, Fig. 19, 3-4.

Derivatio nominis: In honor of the late Dr. Jean-François , for his important contribution to the study of Cretaceous ostracodes.

Material: 380 specimens.

Holotype: C, f, ULVG-10085 (Pl. 6, figs. K-L), sample 27.60 m.

Paratypes: ULVG-10086, ULVG-10061, ULVG-10056.

Dimensions: holotype: L: 0.740, H: 0.400, W: 0.390.

Paratypes: L: 0.740-0.920, H: 0.360-0.430, W: 0.370-0.410.

Type-locality: 9-MO-13-RN, coordinates UTM: 682595E / 9428410N (zone 24S), 27.60 m, Potiguar Basin, Brazil.

Diagnosis: A species of the genus Protocosta with the following characteristics: carapace large to very large, sub-rectangular in lateral view, with surface reticulated and three almost parallel ribs: dorsal, ventral and median; spines in the anterior and posteroventral margins.

Description: carapace large (females) to very large (males), sub-rectangular in lateral view, sub-oval with compressed extremities in dorsal view. LV overlaps the RV along all margins. Maximum height at anterior cardinal angle, maximum width in front of the mid-length, maximum length at mid-height. Dorsal margin almost straight and partially hidden by the dorsal rib; ventral margin almost straight, slightly concave anteriorly. Anterior margin broadly rounded, posterior margin sub-triangular. Anterior and posterior regions compressed. Surface strongly reticulated. Presence of three acute ribs, almost parallel in dorsal, ventral and median regions. The ventral rib is almost straight, the median rib is sinuous and subdued in its anterior part and the dorsal rib is convex. Anteromarginal rib well developed. Anterior and posteroventral margins with spines. Small eye tubercle present. Subcentral tubercle poorly developed. Internal features: LV with smooth posterior and anterior sockets and an elongate and narrow bar.

Sexual dimorphism: females shorter, more inflated and proportionally higher than males. The lateral ribs are more developed in the adult females.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: Protocosta struveae , 1969, recorded in the Paleogene from Argentina, is lower, more elongated, less inflated and with the lateral ribs less developed than P. babinoti sp. nov. The species Protocosta reticulata , , & , 2005 (Maastrichtian of Pernambuco-Paraíba Basin, Brazil) has the posterior margin more rounded, the eye tubercle much more developed and the reticula more prominent.

Protocosta POT 1

(Pl. 6 ![]() , figs.

Q-S)

, figs.

Q-S)

Material: 48 specimens.

Brief description: carapace of medium size, sub-rectangular in lateral view, sub-trapezoidal in dorsal view. LV larger than the right one, with overlap more pronounced in the dorsal margin. Greatest height at anterior cardinal angle, maximum width at posterior third, maximum length below mid-height. Dorsal margin straight, ventral margin slightly convex at mid-length. Anterior margin rounded, posterior margin triangular and acute. Surface strongly reticulated. Presence of three thin ribs: dorsal, median and ventral and marked tubercles near the posteroventral and posterodorsal regions. Anteromarginal rib developed. Subcentral and eye tubercles present.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: This species differs from Protocosta babinoti sp. nov. by the presence of tubercles in the posterodorsal and posteroventral regions, less developed ribs and the position of maximum length, which is below the mid-height.

Genus Paraplatycosta , 1971

Paraplatycosta aff. talayninensis , 1995

(Pl. 7 ![]() , figs.

A-C)

, figs.

A-C)

aff. 1995 Paraplatycosta talayninensis , p. 108-109, Pl. 6, figs. 9-18.

Material: 10 specimens.

Brief description: carapace large, sub-rectangular in lateral view, very narrow in dorsal view. Left valve larger than the right one, with overlap more pronounced in the posterior margin. Greatest height at anterior cardinal angle, maximum width at anterior third. Dorsal margin almost straight, ventral margin slightly concave anteromedially. Anterior margin rounded, posterior margin sub-triangular. Surface covered by asymmetric reticulation; the reticula is smaller around the subcentral tubercle increasing towards the periphery. Anterior and posteroventral margins ornamented with stout spines. Anteromarginal and posteromarginal ribs well developed. Dorsal rib slightly convex. Subcentral and eye tubercles present.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: Besides the general outline similarity with P. talayninensis , 1995 (Upper Santonian, Morocco), the Brazilian species is more elongated, with asymmetrical reticula and posterior margin more acuminate.

Paraplatycosta POT 1

(Pl. 7 ![]() , figs.

D-E)

, figs.

D-E)

Material: 1 specimen.

Brief description: carapace large, sub-rectangular in lateral view, very narrow in dorsal view. Left valve larger than the right one, with overlap more pronounced in the posterodorsal and anterodorsal margins. Maximum height at anterior cardinal angle, maximum width at anterior third. Dorsal margin slightly convex, ventral margin concave at mid-length. Anterior margin broadly rounded, posterior margin rounded to sub-triangular and angulate. Anterior, posterior and posteroventral regions compressed. Surface with scarce and asymmetrical reticulation, with different sizes: large near the periphery, decreasing in size towards the middle. Anteromarginal and posteromarginal ribs prominent; dorsal rib slightly convex, ventral rib short and strongly convex. Presence of strong spines in the anterior and posteroventral margins. Subcentral and eye tubercles well developed.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Remarks: This species was left in open nomenclature due to the scarcity of specimens. The rarity of the genus in the Brazilian margin and the particular ornamentation of this species justify its brief description. It differs from P. aff. talayninensis in having a different outline and ornamentation, particularly in what concerns the dorsal and ventral ribs.

Subfamily Brachycytherinae , 1954

Genus Brachycythere , 1929

"Brachycythere" aff. ilamensis , 1989

(Pl. 7 ![]() , figs.

F-H)

, figs.

F-H)

aff. 1989 Brachycythere ilamensis , p. 611, Fig. B, 3-7.

2000 Brachycythere sp. P1 , , & , p. 422, Fig. 12, 3-4.

Material: 68 specimens.

Brief description: carapace large, sub-triangular in lateral view, inflated in dorsal view. LV valve larger than RV along all margins. Maximum height at anterior cardinal angle, maximum width behind mid-length. Dorsal margin straight, ventral margin almost straight, partially hidden by the inflation of the carapace. Anterior margin obliquely rounded, posterior margin sub-triangular and strongly projected downwards. Anterior and posterior regions compressed. Presence of small eyespots, the left one more prominent. Lateral surface faintly punctated.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution: Santonian–Campanian from Potiguar Basin, Brazil ( et al., 2000; this work).

Remarks: This species is similar to B. ilamensis , 1989, from the Campanian of Iran, but it is smaller, and has no denticles in the anterior margin. Moreover, in the Iranian species the ventrolateral expansion is less pronounced allowing to see the ventral margin. According to (2002) Brachycythere is restricted to North America and the brachycytherines of South America and Africa should belong to a different, but undescribed genus (& , in prep.).

"Brachycythere" cf. angulata , 1951

(Pl. 7 ![]() , figs.

I-J)

, figs.

I-J)

cf. 1951 Brachycythere ledaforma angulata , p. 58, Pl. 2, figs. 11-12.

Material: 8 specimens.

Brief description: carapace large, sub-triangular in lateral view, very inflated in dorsal view. LV valve larger than RV along all margins, more pronounced in the dorsal and ventral margins. Maximum height at anterior cardinal angle, maximum width at mid-length. Dorsal margin straight, ventral margin convex. Anterior margin broadly rounded, posterior margin sub-triangular and acuminate. Anterior and posterior regions compressed. Small and scarce spines in the posteroventral margin. Presence of large eyespots, the left one more prominent. Surface smooth.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution: The species B. angulata , 1951, was originally described in the Santonian from Cameroon and is very common in the Upper Cretaceous from West Africa and Asia Minor, for example: Coniacian–Campanian, Algeria ( & , 1959); Campanian–Maastrichtian, Senegal and Ivory Coast (, 1961); Coniacian–Campanian, Israel ( et al., 1985), Campanian, Oman ( & de , 1989), Santonian–Campanian, Tunisia ( et al., 1995), Cenomanian–Campanian, Egypt (, 1964; , 2000; et al., 2008).

Remarks: Although very similar to B. angulata , 1951, the specimens from Potiguar Basin are shorter and more inflated.

Subfamily Buntoniinae , 1961

Genus Soudanella , 1961

Soudanella laciniosa paucicostata , & , 2000

(Pl. 7 ![]() , figs.

K-N)

, figs.

K-N)

2000 Soudanella laciniosa paucicostata , & , p. 339-340, Figs. 8.19-8.20.

2000 Protobuntonia aff. P. semicostellata , 1951 - et al., p. 432, Figs. 18, 4-6

Material: 27 specimens.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution: Santonian–Campanian, Potiguar Basin.

Soudanella semicostellata (, 1951)

(Pl. 7 ![]() , figs.

O-Q)

, figs.

O-Q)

1951 Buntonia semicostellata , p. 98, Pl. 2, figs. 16-19.

? 1960 Buntonia (P.) semicostellata ().- , p. 164-166, Pl. 10, fig. 3.

1987 Buntonia (P.) semicostellata ().- , p. 55-56, Pl. 18, figs. 1-2; Pl. 22, fig. 17.

1992 Protobuntonia semicostellata ().- , p. 332, Pl. 2, figs. 1-2.

2000 Protobuntonia sp. P6 , , & , p. 432, Fig. 18, 7-8.

Material: 39 specimens.

Age: Santonian–Campanian.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution: Turonian–Santonian, Nigeria (, 1987, 1992); Coniacian, Nigeria (, 1960); Santonian–Campanian, Potiguar Basin, Brazil ( et al., 2000; this work); Campanian, Cameroon (, 1951).

Remarks: Although males have not been observed in the studied material, (1992) illustrated males, which are more elongated.

Subfamily Campylocytherinae , 1960

Genus Leguminocythereis , 1936

Leguminocythereis reymenti , 1973b

(Pl. 7 ![]() , figs.

R-T)

, figs.

R-T)

1960 Leguminocythereis sp.- , p. 139, Pl. 7, fig. 6.

1973b Leguminocythereis reymenti , p. 49-50. Pl. 2, Fig. 3, 4a-b.

1973a Leguminocythereis reymenti - , p. 170-171, Pl. 8.4, fig. 1a-f.

1999a Leguminocythereis sp. , p. 89, Figs. 6.5-6.9.

2000 Leguminocythereis reymenti - et al., p. 430, Figs. 17, 1-2.

2000 Leguminocythereis aff. L. reymenti - et al., p. 340-341, Figs. 8.21-8.22.

Material: 16 specimens.

Age: Santonian.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution: Turonian–Santonian, Nigeria (, 1960; , 1973a, 1973b; , 1999a); Santonian–?Campanian, Potiguar Basin, Brazil ( et al., 2000; et al., 2000; this work).

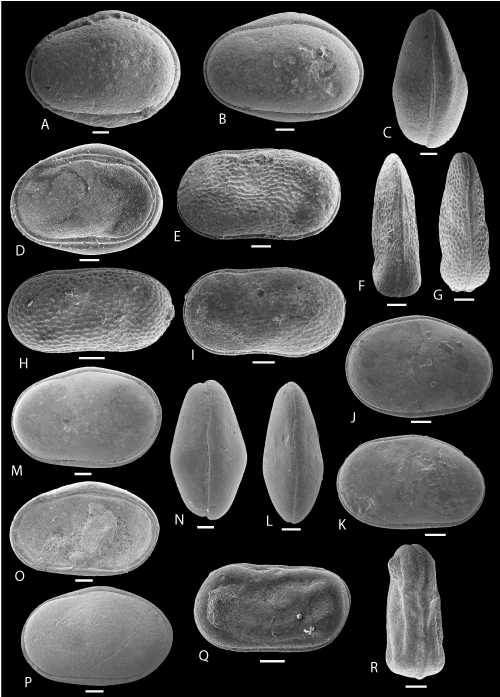

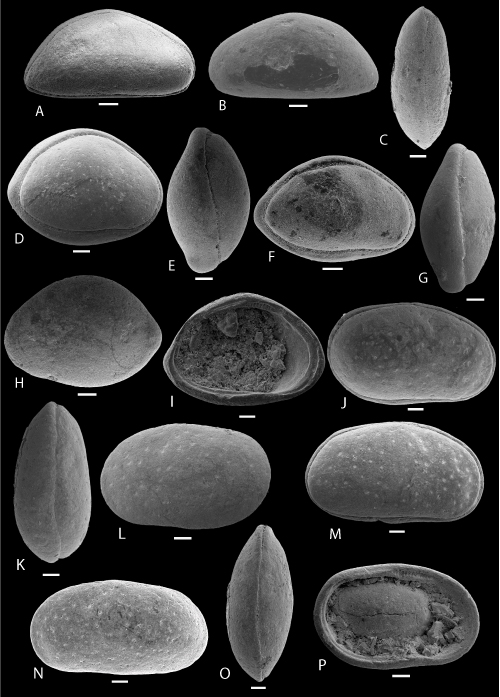

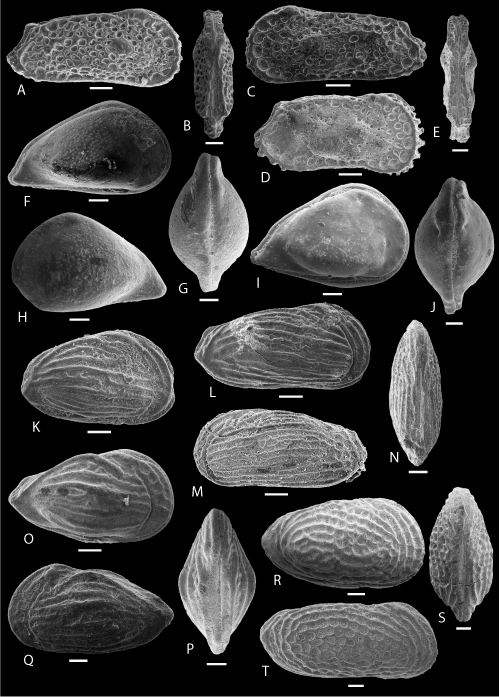

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Plate 1: Scale bar: 100 µm

A-D: Cytherella gambiensis , 1963. A: C, left view, f, ULVG-9840, sample 107.00 m, L: 0.635, H: 0.463, W: 0.360; B: C, left view, m, ULVG-9841, sample 143.90 m, L: 0.843, H: 0.570, W: 0.420; C: C, DV, m, ULVG-9842, sample 143.90 m, L: 0.837, H: 0.559, W: 0.446; D: RV, IV, ULVG-9843, sample 140.30 m, L: 0.869, H: 0.616.

E-I: Cytherella mediatlasica , 1996. E-F: morphotype 1, C, f, ULVG-10104, sample 27.60 m, L: 0.720, H: 0.390, W: 0.250, E: left view, F: DV; G-H: morphotype 2, C, f, ULVG-9847, sample 140.30 m; L: 0.660, H: 0.338, W: 0.230, G: DV, H: left view; I: morphotype 1, C, left view, m, ULVG-10137, sample 29.50 m, L: 0.720, H: 0.350, W: 0.210.

J-L: Cytherella aff. austinensis , 1929. J: C, left view, f, ULVG-9837, sample 140.30 m, L: 0.681, H: 0.490, W: 0.328; K: C, left view, m, ULVG-9838, sample 140.30 m, L: 0.723, H: 0.449, W: 0.303; L: C, DV, m, ULVG-9839, sample 140.30 m; L: 0.730, H: 0.439, W: 0.306.

M-P: Cytherella POT 1. M: C, left view, f, ULVG-9849, sample 140.30 m, L: 0.885, H: 0.569, W: 0.430; N: C, DV, f, ULVG-9850, sample 140.30 m, L: 0.844, H: 0.557, W: 0.485; O: RV, IV, ULVG-9851, sample 140.30 m, L: 0.846, H: 0.539; P: C, left view, m, ULVG-10407, sample 83.90 m, L: 0.820, H: 0.490, W: 0.400.

Q-R: Cytherelloidea POT 1. Q-R: C, ULVG-9853, sample 207.00 m, L: 0.694, H: 0.369, W: 0.270, Q: left view, R: DV.

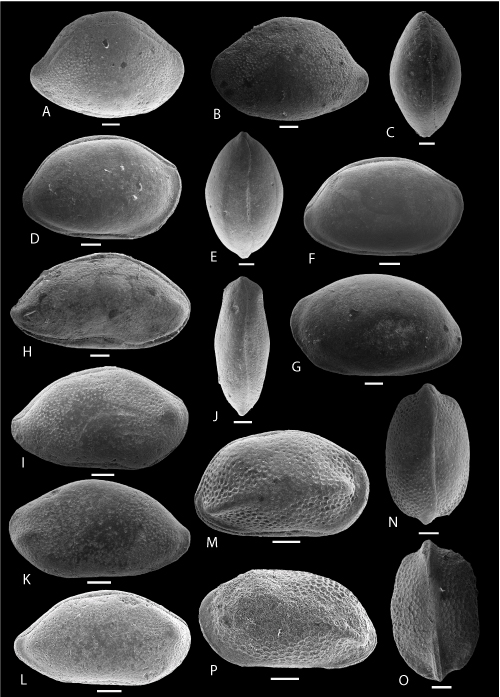

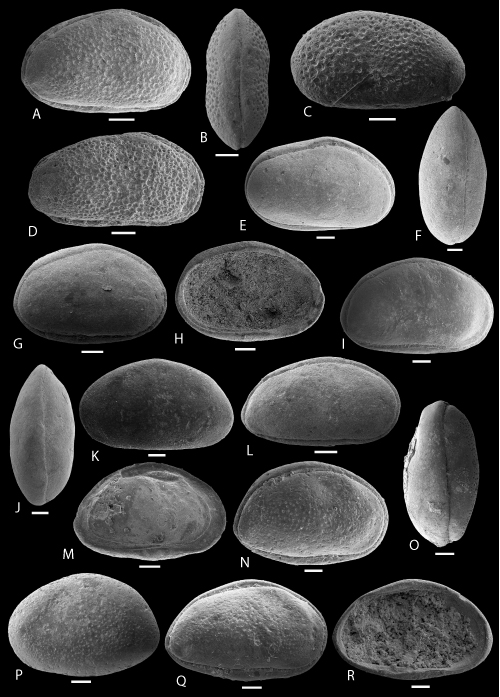

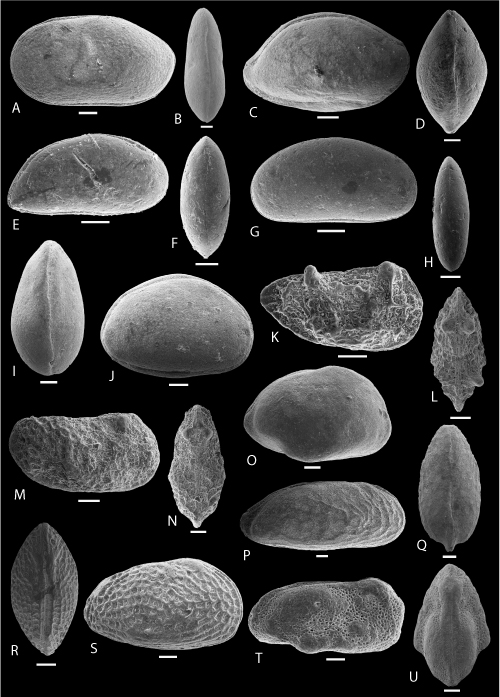

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Plate 2: Scale bar: 100 µm

A-C: Bairdoppilata POT 1. A-B: C, ULVG-9864, sample 81.10 m, L: 0.810, H: 0.526, W: 0.445, A: right view, B: left view, C: C, DV, ULVG-9863, sample 81.10 m, L: 0.894, H: 0.602, W: 0.464.

D-G: Neonesidea POT 1. D: C, right view, ULVG-9866, sample 74.40 m, L: 0.780, H: 0.491, W: 0.465; E: C, DV, ULVG-9867, sample 74.40 m, L: 0.786, H: 0.492, W: 0.478; F-G: C, ULVG-9868, sample 74.40 m, L: 0.740, H: 0.469, W: 0.452, F: right view, G: left view.

H-L: Triebelina anterotuberculata , & sp. nov. H: holotype, C, right view, ULVG-9860, sample 111.80 m, L: 0.940, H: 0.505, W: 0.409; I-K: paratype 1, C, juvenile, ULVG-9859, sample 81.90 m, L: 0.744, H: 0.416, W: 0.310, I: right view, J: DV, K: left view; L: paratype 2, C, juvenile, right view, ULVG-9860, sample 81.90 m, L: 0.860, H: 0.478, W: 0.360.

M-P: Triebelina obliquocostata , & sp. nov. M-O: holotype, C, ULVG- ULVG-9869, sample 74.40 m, L: 0.651, H: 0.378, W: 0.411, M: right view, N: DV, O: VV; P: paratype, C, left view, ULVG-9870, sample 74.40 m; L: 0.704, H: 0.400, W: 0.432.

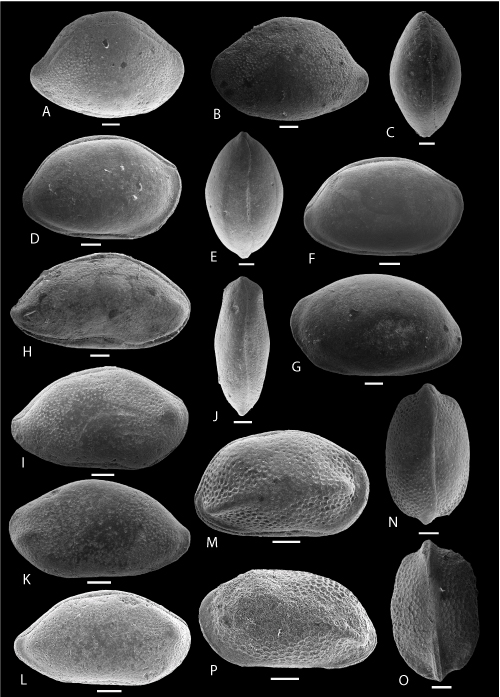

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Plate 3: Scale bar: 100 µm

A-C: Paracypris aff. posteriusacuminatus , 1996. A-C: C, ULVG-9880, sample 140.13 m, L: 0.874, H: 0.434, W: 0.368, A: right view, B: left view, C: DV.

D-I: Cophinia ovalis , & sp. nov. D: holotype, C, right view, f, ULVG- 10389, sample 30.40 m, L: 0.960, H: 0.700, W: 0.560; E: paratype 1, C, DV, f, ULVG- 10384, sample 40.65 m, L: 0.870, H: 0.620, W: 0.500; F-G: paratype 2, C, m, ULVG- 10390, sample 59.60 m, L: 0.920, H: 0.580, W: 0.440, F: right view, G: DV; H: paratype 3, LV, EV, f, ULVG- 10226, sample 39.60 m, L: 0.840, H: 0.600; I: paratype 4, LV, IV, f, ULVG- 10302, sample 50.00 m; L: 0.915, H: 0.649.

J-P: Fossocytheridea potiguarensis , & sp. nov. J: holotype, C, right view, f, ULVG-10181, sample 33.80 m, L: 1.060, H: 0.640, W: 0.540; K: paratype 1, C, DV, f, ULVG-10195, sample 34.05 m, L: 1.000, H: 0.600, W: 0.500; L: paratype 2, C, left view, f, ULVG-10184, sample 33.80 m, L: 0.960, H: 0.600, W: 0.470; M: paratype 3, C, right view, m, ULVG-10187, sample 33.80 m, L: 1.220, H: 0.660, W: 0.520; N: paratype 4, C, left view, m, ULVG-10169, sample 33.00 m, L: 1.040, H: 0.540, W: 0.460; O: paratype 5, C, DV, m, ULVG-10186, sample 33.80 m, L: 1.000, H: 0.640, W: 0.500, P: paratype 6, LV, IV, f, ULVG-10177, sample 33.80 m; L: 0.920, H: 0.580.

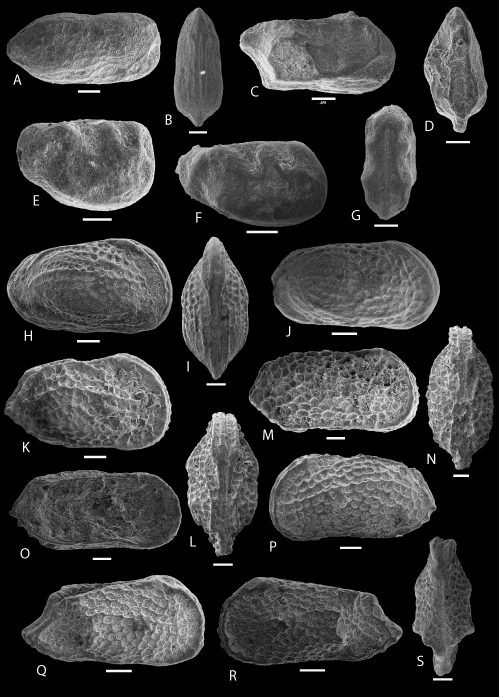

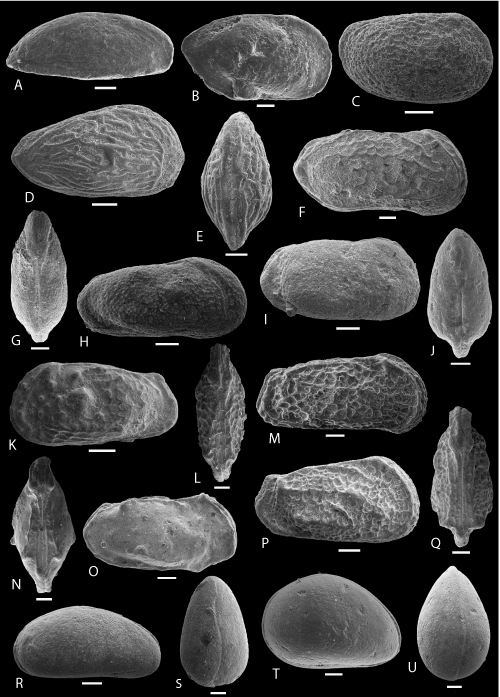

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Plate 4: Scale bar: 100 µm

A-D: Fossocytheridea POT 1. A: C, right view, f, ULVG-10205, sample 38.00 m, L: 0.640, H: 0.380, W: 0.340; B-C: C, f, ULVG-10215, sample 39.60 m, L: 0.620, H: 0.360, W: 0.300, B: DV, C: left view; D: C, right view, m, ULVG-10168, sample 33.00 m, L: 0.690, H: 0.360, W: 0.300.

E-H: Fossocytheridea? POT 2. E-F: C, f, ULVG-10428, sample 75.30 m, L: 0.900, H: 0.540, W: 0.460, E: right view, F: DV; G: C, right view, juvenile, ULVG-10318, sample 55.50 m, L: 0.740, H: 0.480, W: 0.370; H: LV, IV, juvenile, ULVG-10330, sample 58.60 m, L: 0.780, H: 0.500.

I-M: Ovocytheridea anterocompressa , & sp. nov. I-K: holotype, C, f, ULVG-10283, sample 47.60 m, L: 0.840, H: 0.520, W: 0.400, I: right view, J: DV, K: left view; L: paratype 1, C, right view, m, ULVG-10237, sample 40.20 m, L: 0.780, H: 0.420, W: 0.320; M: paratype 2, LV, IV, f, ULVG-10160, sample 31.80 m, L: 0.700, H: 0.460.

N-R: Ovocytheridea triangularis , & sp. nov. N: holotype, C, right view, f, ULVG-10112, sample 27.90 m, L: 0.880, H: 0.600, W: 0.440; O: paratype 1, C, DV, f, ULVG-10119, sample 28.30 m, L: 0.800, H: 0.540, W: 0.440; P: paratype 2, C, left view, f, ULVG-10090, sample 27.60 m, L: 0.840, H: 0.600, W: 0.460; Q: paratype 3, C, right view, m, ULVG-10075, sample 26.70 m, L: 0.900, H: 0.480, W: 0.380, R: paratype 4, LV, IV, ULVG-10149, sample 30.20 m, L: 0.890, H: 0.560.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Plate 5: Scale bar: 100 µm (A-N); 50 µm (O-S)

A-D: Ovocytheridea cf. producta , 1962. A-C: C, ULVG-9965, sample 140.30 m, L: 0.693, H: 0.415, W: 0.348, A: right view, B: DV, C: left view; D: RV, IV, ULVG-9966, sample 140.30 m, L: 0.700, H: 0.384.

E-I: Perissocytheridea jandairensis , & sp. nov. E: holotype, C, right view, f, ULVG-10193, sample 34.00 m, L: 0.540, H: 0.280, W: 0.380; F: paratype 1, C, DV, f, ULVG-10259, sample 46.05 m, L: 0.520, H: 0.280, W: 0.320; G: paratype 2, C, right view, m, ULVG-10179, sample 33.80 m, L: 0.610, H: 0.280, W: 0.340; H: paratype 3, C, DV, ULVG-10260, sample 46.05 m, L: 0.520, H: 0.240, W: 0.220; I: paratype 4, LV, IV, f, ULVG-10078, sample 34.00 m, L: 0.420, H: 0.220.

J-L: Eocytheropteron POT 1. J-K: C, f, ULVG-9900, sample 132.40 m, L: 0.458, H: 0.255, W: 0.271, J: right view, K: DV; L: C, right view, m, ULVG-9899, sample 140.30 m, L: 0.533, H: 0.256, W: 0.285.

M-N: Eocytheropteron POT 2. M-N: C, ULVG-9898, sample 140.13 m, L: 0.520, H: 0.270, W: 0.299, M: right view, N: DV.

O-S: Semicytherura musacchioi , & sp. nov. O-P: holotype, C, m, ULVG-10089, sample 27.60 m, L: 0.370, H: 0.180, W: 0.160, O: right view, P: VV; Q-R: C, f, ULVG-9921, sample 67.40 m, L: 0.314, H: 0.152, W: 0.143, Q: DV, R: left view; S: C, right view, f, ULVG-10098, sample 27.60 m, L: 0.350, H: 0.170, W: 0.152.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Plate 6: Scale bar: 50 µm (A-G); 100 µm (H-S)

A-B: Semicytherura POT 2. A-B: C, ULVG-10202, sample 37.10 m, L: 0.381, H: 0.180, W: 0.170, A: right view, B: DV.

C-D: Semicytherura POT 3. C-D: C, ULVG-9920, sample 81.90 m, L: 0.379, H: 0.175, W: 0.177, C: right view, D: DV.

E-G: Vesticytherura? POT 1. E, G: C, f, ULVG-9920, sample 53.95 m, L: 0.270, H: 0.190, W: 0.120; E: right view; F: C, right view, m, ULVG-10313, sample 54.90 m, L: 0.300, H: 0.150, W: 0.120; G: DV.

H-J: Langiella POT 1. H-I: C, f, ULVG-10284, sample 48.40 m, L: 0.720, H: 0.400, W: 0.350, H: right view, I: DV; J: C, right view, m, ULVG-10225, sample 39.60 m, L: 0.680, H: 0.340, W: 0.340.

K-P: Protocosta babinoti , & sp. nov. K-L: holotype, C, f, ULVG-10085, sample 27.60 m, L: 0.740, H: 0.400, W: 0.390, K: right view, L: DV; M-N: paratype 1, C, m, ULVG-10086, sample 27.60 m, L: 0.880, H: 0.410, W: 0.410, M: right view, N: DV; O: paratype 3, LV, IV, m, ULVG-10061, sample 26.40 m, L: 0.920, H: 0.430, P: paratype 4,C, left view, m, ULVG-10056, sample 26.25 m, L: 0.740, H: 0.360, W: 0.370.

Q-S: Protocosta POT 1. Q,S: C, ULVG-10290, sample 49.65 m, L: 0.700, H: 0.320, W: 0.300, Q: right view; R: C, left view; ULVG-10344, sample 59.60 m, L: 0.685, H: 0.320, W: 0.310; S: DV.

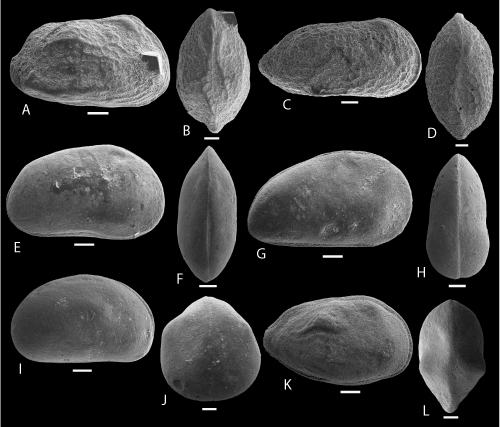

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Plate 7: Scale bar: 100 µm

A-C: Paraplatycosta aff. talayninensis , 1995. A-B: C, ULVG-10130, sample 29.20 m, L: 0.740, H: 0.320, W: 0.210, A: right view, B: DV; C: C, left view, ULVG-10126, sample 29.20 m, L: 0.700, H: 0.310, W: 0.220.

D-E: Paraplatycosta POT 1. D-E: C, ULVG-10021, sample 140.13 m, L: 0.790, H: 0.310, W: 0.220, D: right view, E: DV.

F-H: "Brachycythere" cf. ilamensis , 1989. F: C, right view, ULVG-10039, sample 81.90 m, L: 0.800, H: 0.490, W: 0.490; G: C, DV, ULVG-10441, sample 81.10 m, L: 0.720, H: 0.440, W: 0.440; H: C, left view, ULVG-10394, sample 81.90 m, L: 0.760, H: 0.480, W: 0.460.

I-J: "Brachycythere" cf. angulata , 1951. I-J: C, ULVG-10117, sample 28.30 m, L: 0.820, H: 0.420, W: 0.500, I: right view, J: DV.

K-N: Soudanella laciniosa paucicostata , & , 2000. K: C, right view, f, ULVG-10044, sample 140.30 m, L: 0.607, H: 0.365, W: 0.257; L: C, right view, m, ULVG-10045, sample 140.30 m, L: 0.790, H: 0.365, W: 0.312; M-N: C, m, ULVG-10046, sample 140.30 m, L: 0.779, H: 0.355, W: 0.294, M: left view, N: DV.

O-Q: Soudanella semicostellata (, 1951). O-P: C, ULVG-10041, sample 149.95 m, L: 0.729, H: 0.401, W: 0.379, O: right view, P: DV; Q: C, left view, ULVG-10042, sample 140.13 m, L: 0.900, H: 0.474, W: 0.428.

R-T: Leguminocythereis reymenti , 1973b. R-T: C, f, ULVG-9982, sample 140.13 m, L: 0.917, H: 0.490, W: 0.490, R: right view S: DV; T: C, right view, m, ULVG-9983, sample 140.13 m, L: 1.152, H: 0.493, W: 0.492.

Appendix 1: Illustrated species.

This appendix (Pls. 8-10) includes the taxa that remained undetermined due to the scarcity, preservation, reduced stratigraphic value or even to the impossibility of inclusion in any taxon described up to now.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Plate 8: Scale bar: 100 µm (A-J); 50 µm (K-U)

A-B: Cytherella POT 2. A-B: C, ULVG-9852, sample 140.30 m, L: 0.820, H: 0.440, W: 0.300, A: left view, B: DV.

C-D: Bairdoppilata POT 2. C-D: C, ULVG-9862, sample 204.00 m, L: 0.740, H: 0.450, W: 0.434, C: right view, D: DV.

E-F: Paracypris POT 5. E-F: C, ULVG-10139, sample 29.70 m, L: 0.530, H: 0.360, W: 0.220, E: right view, F: DV.

G-H: "Bythocypris" POT 1. G-H: C, ULVG-10131, sample 29.50 m, L: 0.600, H: 0.310, W: 0.200, G: right view, H: DV.

I-J: Ovocytheridea POT 1. I-J: C, ULVG-9972, sample 204.00 m, L: 815, H: 0.530, W: 0.420, I: DV, J: right view.

K-L: Acuminacythere? POT 2. K-L: C, ULVG-10122, sample 28.45 m, L: 0.310, H: 0.180, W: 0.140, K: right view, L: DV.

M-N: Eucytherura aff. speluncosus (, 1995). M-N: C, ULVG-10400, sample 81.90 m, L: 0.412, H: 0.216, W: 0.200, M: right view, N: DV.

O: Kroemmelbeinella? POT 1. O: C, right view, ULVG-10315, sample 54.90 m, L: 0.520, H: 0.300, W: 0.340.

P-Q: Metacytheropteron? POT 2. P-Q: C, ULVG-9905, sample 85.15 m, L: 0.445, H: 0.220, W: 0.260, P: right view, Q: DV.

R-S: Metacytheropteron? POT 3. R-S: C, ULVG-9907, sample 74.40 m, L: 0.480, H: 0.260, W: 0.240, R: DV, S: right view.

T-U: Microceratina? POT 1. T-U: C, ULVG-10245, sample 41.30 m, L: 0.450, H: 0.210, W: 0.290, T: right view, U: DV.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Plate 9: Scale bar: 50 µm (A-C; R-U); 100 µm (D-Q)

A: Pelecocythere POT 2. A: C, right view, ULVG-10124, sample 29.20 m, L: 380, H: 0.130, W: 0.185.

B: Phlyctocythere? POT 2. B: C, right view, ULVG-10121, sample 28.45 m, L: 0.480, H: 0.260, W: 0.165.

C: Sagmatocythere? POT 1. C: C, right view, ULVG-9928, sample 62.30 m, L: 0.279, H: 0.158, W: 0.145

D-E: Soudanella POT 1. D-E: C, ULVG-10043, sample 140.30 m, L: 0.742, H: 0.400, W: 0.340, D: right view, E: DV.

F: Leguminocythereis? POT 1. F: C, right view, ULVG-9984, sample 207.00 m, L: 1.050, H: 0.505, W: 0.490.

G-H: Deroocythere? POT 1. G-H: C, ULVG-9985, sample 140.30 m, L: 0.706, H: 0.335, W: 0.302, G: DV, H: right view.

I-J: Trachyleberididae indet. gen. 2. I-J: C, ULVG-10022, sample 185.50 m, L: 0.720, H: 0.320, W: 0.340, I: right view, J: DV.

K: Trachyleberididae indet. gen. 3. K: C, left view, ULVG-10334, sample 58.60 m, L: 0.650, H: 0.305, W: 290.

L-M: Trachyleberididae indet. gen. 4. L-M: C, ULVG-10372, sample 74.70 m, L: 0.940, H: 0.430, W: 0.375, L: DV, M: right view.

N-O: Trachyleberididae indet. gen. 5. N-O: C, ULVG-10366, sample 75.30 m, L: 0.840, H: 0.410, W: 0.400, N: DV, O: right view.

P-Q: Trachyleberididae indet. gen. 6. P-Q: C, ULVG-10141, sample 29.70 m, L: 0.720, H: 0.360, W: 0.320, P: right view, Q: DV.

R-S: Xestoleberis POT 2. R-S: C, ULVG-10381, sample 82.70 m, L: 0.370, H: 0.180, W: 0.230, R: right view, S: DV.

T-U: Xestoleberis POT 3. T-U: C, ULVG-10070, sample 26.70 m, L: 0.410, H: 0.260, W: 0.242, T: right view, U: DV.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image.

Plate 10: Scale bar: 50 µm (A-D; I-L); 100 µm (E-H)

A-B: Indet. gen. 3 POT 2. A-B: C, ULVG-9906, sample 74.40 m, L: 0.440, H: 0.221, W: 0.280, A: right view, B: DV.

C-D: Indet. gen. 4 POT 2. C-D: C, ULVG-9922, sample 60.20 m, L: 0.540, H: 0.265, W: 0.295, C: right view, D: DV.

E-F: Indet. gen. 5 POT 2. E-F: C, ULVG-9876, sample 74.40 m, L: 0.790, H: 0.470, W: 0.340, E: right view, F: DV.

G-H: Indet. gen. 6 POT 1. G: C, right view, m, ULVG-10282, sample 47.60 m, L: 0.810, H: 0.450, W: 0.310; H: C, DV, f, ULVG-10351, 60.20 m, L: 0.740, H: 0.442, W: 0.390.

I-J: Indet. gen. 7 POT 1. I-J: C, ULVG-10380, sample 74.40 m, L: 0.360, H: 0.200, W: 0.330, I: right view, J: DV.

K-L: Indet. gen. 8 POT 1. K: C, right view, ULVG-10297, sample 50.00 m, L: 0.430, H: 0.260, W: 0.260; L: C, DV, ULVG-10311, sample 54.90 m, L: 0.440, H: 0.250, W: 0.275.

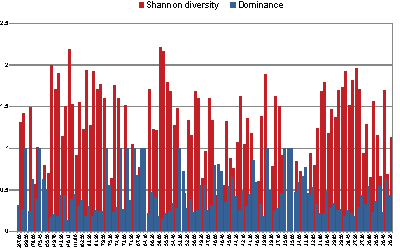

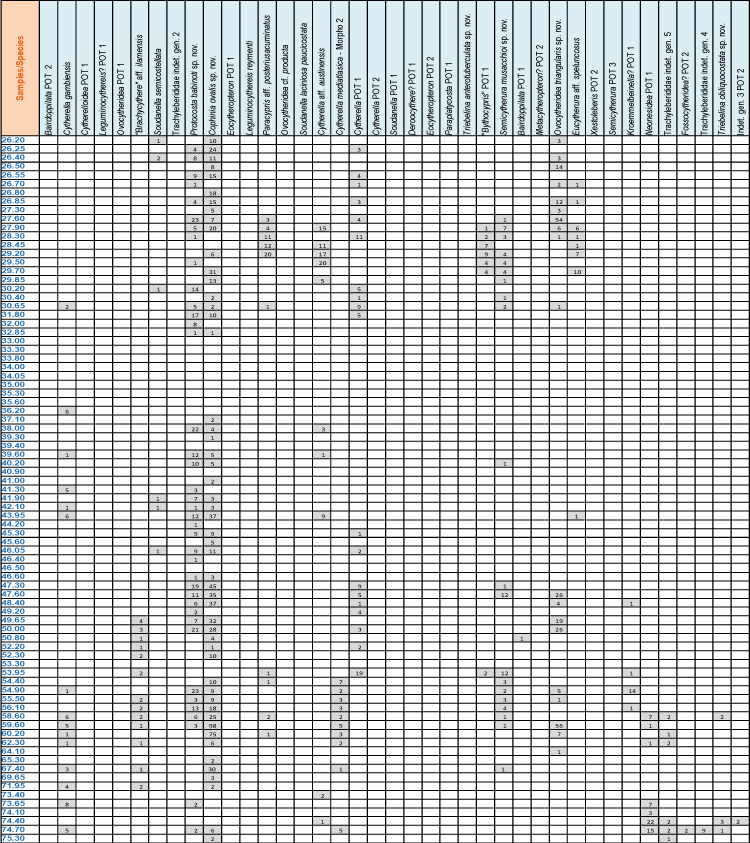

The Santonian–Campanian fauna of the Potiguar Basin is represented by 64 taxa, including nine new species

(Fig. 3 ![]() ;

Appendix 2

;

Appendix 2 ![]() ). In general, it records diversified shallow water assemblages, at the base of the well. At some levels, typical mixohaline assemblages are present and towards the top the marine fauna is reestablished, but poorly diversified and with high dominance. The Shannon diversity and dominance values vary along the studied interval, characterizing environmental fluctuations

(Fig. 4

). In general, it records diversified shallow water assemblages, at the base of the well. At some levels, typical mixohaline assemblages are present and towards the top the marine fauna is reestablished, but poorly diversified and with high dominance. The Shannon diversity and dominance values vary along the studied interval, characterizing environmental fluctuations

(Fig. 4 ![]() ).

).

The interval 207 m - 79.50 m is exclusively represented by marine species, some of them with long range (e.g., Cytherella gambiensis, Brachycythere aff. ilamensis, Cophinia ovalis sp. nov.). Thirty-three taxa are identified in this interval, being the Platycopida the dominant taxa (52%), represented by the species Cytherella aff. austinensis, Cytherella gambiensis and Cytherella mediatlasica. Some authors (e.g., & , 1994; et al., 2003; et al., 2005; & , 2007; & , 2008) claimed that dominance of platycopids in ostracode assemblages could be regarded as a signal of dysaerobic conditions on the sea floor, based on the idea that the filter feeding platycopids, being able to pass more water over their respiratory surface were better adapted to survive in waters of reduced oxygen concentration. More recently, & (2009), based on evidence from living ostracodes, established that platycopids are only occasionally dominant in levels of reduced oxygen, but frequently they are not. In this specific interval, the platycopids, although dominant, occur associated with many marine species and probably do not indicate low oxygen levels. Another factor that reinforces this hypothesis is the presence of Brachycythere, a genus that does not tolerate low oxygen levels ( & , 2008).

Based on the faunal composition, we infer an inner-outer platform environment for this first interval (207 m - 79.50 m). Although the faunal association indicates shallow water, some evidence suggests that depth may have varied along this range, particularly in the interval 143.90 m - 79.50 m, with a higher diversity (average of 1.60), lower dominance and presence of typical marine stenohaline ostracodes. The morphological variation in specimens of Eucytherura aff. speluncosus, which have eye tubercles less developed than the specimens at the top of the well and are associated with brackish species, points to deeper water. Additionally, Soudanella semicostellata and Leguminocythereis reymenti have been found in upper bathyal environment in the Upper Cretaceous of Nigeria (, 1999a).

The same environment of inner-outer platform seems to occur in the interval at 76 m-73.65 m, directly above this first one but the number of species and abundance decrease (16 taxa, distributed among 158 specimens). Other dominant taxa are: Neonesidea POT 1, indet. gen. 7 POT 1 and Cytherella gambiensis.

From the depth 73.40 m upwards, the fauna is dominated by cytherideids, indicating shallower waters. Following a trend of establishment of mixohaline conditions, from 46.60 m, there is a reduction in diversity (average of 1.07) and the typically mixohaline genera Fossocytheridea and Perissocytheridea occur in great abundance. In some levels (e.g., 33.80 m), the association of Fossocytheridea/Perissocytheridea represents almost 90% of the specimens and, in other levels, it is associated with some marine species such as Protocosta babinoti sp. nov. and Cophinia ovalis sp. nov. Previous studies have demonstrated that the association of Fossocytheridea/Perissocytheridea is characteristic of marginal marine environments ( et al., 1996; et al., 2002, 2003, 2009; & , 2010; et al., 2011). The species Ovocytheridea anterocompressa sp. nov. is also very abundant in this association, reinforcing the genus Ovocytheridea as an important indicator of marginal marine environment, as had been discussed by & (1974), (1991) and et al. (2008).

In the interval 29.85 m - 26.20 m, a marine fauna is established again, with the dominance of Cophinia ovalis sp. nov., Ovocytheridea triangularis sp. nov., and Cytherella aff. austinensis. Some species are noteworthy because of their ecology, in special Cophinia ovalis sp. nov. and Ovocytheridea triangularis sp. nov. The former species is widely distributed and seems to be euryhaline, due to its association with both marine and mixohaline species; Ovocytheridea triangularis sp. nov. is a recurrent species in the marine intervals, but does not occur at mixohaline levels, differing from the distribution of Ovocytheridea anterocompressa sp. nov.