Content

[Introduction] [About the name Lingula]

[About the name anatina]

[About the usage of the term linguliform ...]

[Bibliographic references] [Figures] and ... [Tables]

BrachNet, 20, Rue Chaix, F-13007 Marseille (France)

Manuscript online since December 10, 2008

The first descriptions of Lingula were made from then extant specimens by three famous French scientists: , , and . The genus Lingula was created in 1791 (not 1797) by and in 1801 named the first species L. anatina, which was then studied by (1802). In 1812 the first fossil lingulids were discovered in the Mesozoic and Palaeozoic strata of the U.K. and were referred to Lingula on the basis of similarity in the form of the shell. In the 1840's other linguliform brachiopods from the Palaeozoic were described. The similarity of the shell form of the extant Lingula and these fossils led in 1859 to create the description "living fossil" in his book "On the Origin of Species". Thereafter, this Darwinian concept became traditional in that Lingula was considered to lack morphological evolutionary changes. Although denounced as scientifically incorrect for more than two decades, the concept still remains in many books, publications and Web sites, perhaps a witness to palaeontological conservatism.

Lingula; brachiopod; anatina; ; living fossil.

C.C. (2008).- On the history of the names Lingula, anatina, and on the confusion of the forms assigned them among the Brachiopoda.- Carnets de Géologie / Notebooks on Geology, Brest, Article 2008/08 (CG2008_A08)

De l'origine historique des noms lingule, Lingula, anatina, et de la confusion des formes chez les Brachiopodes.- Les premiers auteurs à publier sur les lingules – Lingula - furent

français : créa le genre Lingula en

1791

[et non en 1797], cette date acceptée par tous les auteurs jusqu'à la fin du

XIXème siècle et confirmée dans ce travail. Elle fut

remise en cause à partir du début du XXème siècle et remplacée officiellement par 1797 par la Commission Internationale de Nomenclature zoologique en

1982,

puis confirmée en 1985. La signification de lingule ou lingula

(ou ligula) est communément considérée comme un diminutif

(signifiant languette ou élément en forme de langue) du latin lingua "langue". D'autres possibilités peuvent être suggérées, comme un diminutif savant du latin lingua + le suffixe –ula [en français –ule] ou encore une autre traduction du latin ligula ou lingula à savoir cuillère.

(1801) puis

(1802) décrivirent la première espèce du genre sous Lingula anatina. L'origine du nom d'espèce est

inconnue, mais, en latin, ce nom évoque une ressemblance avec le "bec de cane" cité par

(1798). Auparavant (1758) indiquait qu'il s'agit

"d'une espèce particulière de conque anatifère",

anatina signifiant en latin du canard ou appartenant au canard.

J. (1812) se basa sur la ressemblance de forme de la coquille pour décrire les premières lingules fossiles dans le Jurassique de Grande-Bretagne. À partir des années 1840, notamment avec la description des "Lingula-flags" dans le Paléozoïque inférieur du Pays de

Galles, il y a amalgame, devenu classique, de la forme – linguliforme – entre les espèces actuelles de Lingula et les lingulides fossiles paléozoïques et mésozoïques.

L'extension géologique des Lingula à travers tout le Phanérozoïque a influencé

(1859) lors de la création du terme "fossile vivant". Dans son livre "Sur l'origine des espèces", il fait plusieurs fois référence aux

lingules.

Depuis cette époque, les Lingula ont été décrites, dans la plupart des traités de paléontologie, "avec une forme pratiquement inchangée depuis leur origine au

Cambrien, il y a environ 550 Millions d'années". La conséquence en est que tout brachiopode fossile linguliforme a été décrit, et l'est parfois encore de nos

jours, comme appartenant au genre Lingula sur ce seul critère.

Pourtant, le traditionnel concept introduit par que les Lingula sont des

"fossiles vivants" a été rejeté depuis plus de 20 ans, et auparavant par

(1798). La persistance de cette hérésie scientifique ne peut s'expliquer que par le conservatisme de la communauté internationale des paléontologues avec des modèles difficilement remis en question.

Lingula ; brachiopode ; anatina ; ; fossile-vivant.

Offered by the Web (Internet) the facility to examine old scientific work in facsimile makes it possible to review and to clarify the origin of the name Lingula and that of its type species L. anatina. The Web also makes it possible to show that (, 1859) who originated the concept of living fossil for Lingula, was wrong because his conclusion was not based on systematics, and has been denounced for more than 20 years. Nevertheless, it continues to be postulated by some palaeontologists in their publications, books and Web sites.

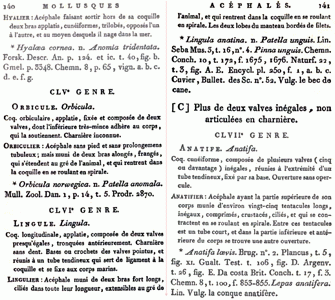

Until the end of the XIXth century the brachiopods were classified as molluscs. (1806) proposed the creation of a 5th order of molluscs under the name Brachiopoda. However, he noted (1806, p. 154) that nine years earlier had already suggested this subdivision. Indeed, (1798), then (1801), subdivided Molluscs, inserting in the Acephal Molluscs the four brachiopod genera known at that time: Lingula, Orbicula, Crania and Terebratula. (1802) included these groups in the "Coquilles inaequivalves" and all the lamellibranchs in the "équivalves". This classification has been largely overlooked as (1955) has pointed out. (1828) divided the class Brachiopoda into three families, one being the family Lingulaceae (now the superfamily Linguloidea , 1828 and the family Lingulidae , 1828) with Lingula.

At the end of the XIXth century, (1888, p. 40) separated the Brachiopods from the Molluscs. He included Brachiopoda, Bryozoa (Ectoprocta) and Phoronida in his Tentaculata (= Molluscoidea) (see also , 1955).

The first authors who published on Lingula were French, respectively , 1 and 1 (Table 1 ![]() ). Before the creation of the genus Lingula by (1791), (1705) called it a gastropod which was later named Scrutus , 1810. (1758, 1767) placed these animals as gastropod molluscs under the name Patella unguis (specimen from Ambon island in the Moluccas, Indonesia), but as stated by (1798, 1802) (Figs. 1

). Before the creation of the genus Lingula by (1791), (1705) called it a gastropod which was later named Scrutus , 1810. (1758, 1767) placed these animals as gastropod molluscs under the name Patella unguis (specimen from Ambon island in the Moluccas, Indonesia), but as stated by (1798, 1802) (Figs. 1 ![]() - 2

- 2 ![]() - 3

- 3 ![]() ) he described only one detached valve without a pedicle. Along the coast of this island three species of Lingula have been reported: L. anatina by various authors of the XVIIIth and XIXth centuries, and recently L. reevei and L. rostrum by and

(1979). No specimen of Lingula has been found in 's collections. Some authors like

(1789) confirmed the name Patella unguis. According to and (1817) "(...) [1786] et [1786] qui surent qu'elle avait deux valves, lui donnèrent l'un le nom de mytilus lingua, l'autre celui de pinna unguis" (see also , 1888; Fig. 4

) he described only one detached valve without a pedicle. Along the coast of this island three species of Lingula have been reported: L. anatina by various authors of the XVIIIth and XIXth centuries, and recently L. reevei and L. rostrum by and

(1979). No specimen of Lingula has been found in 's collections. Some authors like

(1789) confirmed the name Patella unguis. According to and (1817) "(...) [1786] et [1786] qui surent qu'elle avait deux valves, lui donnèrent l'un le nom de mytilus lingua, l'autre celui de pinna unguis" (see also , 1888; Fig. 4 ![]() ).

).

Mytilus lingua is catalogued by (1786) on the annotated list (which is referred to him) for the auction of the collection of Lady Margaret , duchess of Portland, after her death in 1785. For some taxa he used the names given them by Daniel Carl (1733-1782), a pupil of Karl von and curator of the collection of the duchess. He indicated these taxa by an "S" following the name. 's manuscripts remain unpublished and are preserved at the Natural History Museum of London. Until 1965, most of the quotations of the "Portland Catalogue" were attributed to (see , 1888; Fig. 4 ![]() ). Then, (1965) assigned all the names in the catalogue to (1786), and this revision was adopted by many malacologists. Several authors, such as & (1817) and (1888), assigned Mytilus lingua to (Fig. 4

). Then, (1965) assigned all the names in the catalogue to (1786), and this revision was adopted by many malacologists. Several authors, such as & (1817) and (1888), assigned Mytilus lingua to (Fig. 4 ![]() ). I was not able to consult 's manuscripts 's list (1786), or the work of (1965).

). I was not able to consult 's manuscripts 's list (1786), or the work of (1965).

Moreover oddly enough Mytilus lingua was considered (see , 1964; , 1982) as a possibility for the type species of the genus Lingula. But in the end L. anatina , 1801 was accepted and Mytilus lingua removed (, 1985), owing to a doubtful identification and the absence of acceptance (see below).

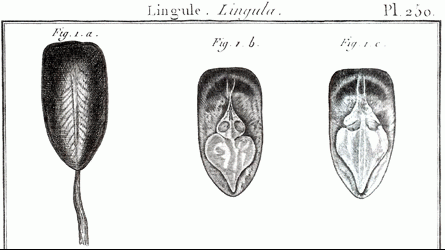

(1791 [1789]) created the genus Lingula (Fig. 5 ![]() ) in Volume 1 of the Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature : vers, coquilles, mollusques et polypes divers, written by as the sole author. Three volumes were published by Charles Joseph (Paris and Liège) and in several editions.

) in Volume 1 of the Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature : vers, coquilles, mollusques et polypes divers, written by as the sole author. Three volumes were published by Charles Joseph (Paris and Liège) and in several editions.

Volume 1 in which Lingula is figured is dated 1789, but was published in 1791 (Fig. 5 ![]() ), as confirmed in the "Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé" (A.T.I.L.F., 2007): "1791 lingule (JG , Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature, I, 151a,

Pl. 250 dans Compte rendu de R. sur les datations de DDL t. 20, à paraître dans R. Ling. rom. t. 47)" (see 1982; 1982). The etymology of lingule (French), and lingula or ligula (Latin) is probably a diminutive meaning tongue or tongue-shaped, from the Latin lingua "tongue". Another possibility proposed in the "Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé" (A.T.I.L.F., 2007)

is that it is a scholarly diminutive of the Latin lingua+suffix-ule (= little, small): this suffix is associated with a name from the Latin: -ulus, -ula, -ulum.This usage is found mainly in scientific works, particularly those of the life sciences. Another etymology: lingula may be derived from the Latin ligula, sometimes lingula, "spoon", with reference to the spoon-shape of the animal formed by the shell and the pedicle (Pers. Comm. R. ).

), as confirmed in the "Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé" (A.T.I.L.F., 2007): "1791 lingule (JG , Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature, I, 151a,

Pl. 250 dans Compte rendu de R. sur les datations de DDL t. 20, à paraître dans R. Ling. rom. t. 47)" (see 1982; 1982). The etymology of lingule (French), and lingula or ligula (Latin) is probably a diminutive meaning tongue or tongue-shaped, from the Latin lingua "tongue". Another possibility proposed in the "Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé" (A.T.I.L.F., 2007)

is that it is a scholarly diminutive of the Latin lingua+suffix-ule (= little, small): this suffix is associated with a name from the Latin: -ulus, -ula, -ulum.This usage is found mainly in scientific works, particularly those of the life sciences. Another etymology: lingula may be derived from the Latin ligula, sometimes lingula, "spoon", with reference to the spoon-shape of the animal formed by the shell and the pedicle (Pers. Comm. R. ).

Some vernacular names for Lingula: "moule-à-queue" in New Caledonia; "bec de cane" along some coasts in the Indian Ocean (, 1798); "shamisen-gai" in Japan. The name is related to its similarity to the shamisen, a Japanese lute of Chinese origin.

(1798) (Fig. 1 ![]() ) assigned the genus Lingula to (1791) (Fig. 3

) assigned the genus Lingula to (1791) (Fig. 3 ![]() ). Throughout the XIXth century (1880) and several other authors indicated the year 1789 (Fig. 4

). Throughout the XIXth century (1880) and several other authors indicated the year 1789 (Fig. 4 ![]() ), as follows: Lingula anatina, , Hist. des vers. Encycl. Méth.

Pl. CCl, fig. 1 a, b, c, 1789. Others like d' (1852) list 1791. I could not find this reference 1789, but found two under (1791) with plates 172-314 and (ca. 1793) with plates 199-488.

), as follows: Lingula anatina, , Hist. des vers. Encycl. Méth.

Pl. CCl, fig. 1 a, b, c, 1789. Others like d' (1852) list 1791. I could not find this reference 1789, but found two under (1791) with plates 172-314 and (ca. 1793) with plates 199-488.

Starting in the XXth century, various authors indicate , 1797 as the date of the creation of the genus Lingula. (1964) in accordance with the publication dates of the Encyclopédie Méthodique as printed by and (1906, p. 581), obtained in 1966 from the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (, 1982, 1985) a change of year for Lingula from 1791 to 1797. Recently, the data published by (2003) and and (2003) confirm 's proposal. The volumes of plates for the Histoire Naturelle des Vers volumes were published in the form of a Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique. However, their review of the publication of the Encyclopédie méthodique and of the Tableau, has several gaps in their compilation of the editions that appeared before 1797, as well as some incomplete references. For example 's Tome 1, edited in 1792 should be quoted as: Encyclopédie Méthodique, ou par ordre de matières: par une société de gens de lettres, de savants et d'artistes : précédée d'un vocabulaire universel, servant de table pour tout l'ouvrage, ornée des portraits de MM. et d', premiers éditeurs de l'Encyclopédie [26, a], 1 Histoire Naturelle des Vers, tome 1, p. 1-757. , Paris.

So the date 1797 for the first description of Lingula is wrong and we must return to the original date of 1791, which is the correct one. Many successive editions under various titles, as well as gaps in the bibliographic searches may explain this error. After the death of Charles-Joseph in 1798, his daughter Thérèse-Charlotte , wife of Henri , the associate of , assured the publication. Such errors in the dates of the first publication of old books are common. Another example concerns the first editions of 's volume 3: its year and pagination range between 1758, the correct one, 1759 (p. [1-24], 1-108, Pl. 1-116; or 212 p., 116 plates; or 511 p., 116 Pls.) and 1761 (511 p., 116 Pls.). Several other editions have been published by scientific editors, e.g., , and under et alii (1828), and recently et alii (2005).

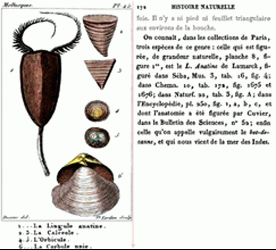

Lingula , 1791 as a genus was named 10 years before the description of the first species L. anatina , 1801. In Plate 16, fig. 4, (1758) figured for the first time two lingulide2 specimens stored in his own collection (Fig. 6 ![]() ). After Albert 's death in 1736, many of the specimens in his collection were auctioned off in 1752 and dispersed all over Europe. Among them the lingulids2 and other specimens figured in the plates were acquired by the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle de Paris. These lingulide specimens were used by (1801) to describe the new species Lingula anatina (Fig. 7

). After Albert 's death in 1736, many of the specimens in his collection were auctioned off in 1752 and dispersed all over Europe. Among them the lingulids2 and other specimens figured in the plates were acquired by the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle de Paris. These lingulide specimens were used by (1801) to describe the new species Lingula anatina (Fig. 7 ![]() ). Appointed in 1793 at the Muséum de Paris as a professor on insects and worms, was not as skilled as in making detailed analyses, so he gave easy access to his specimens, in particular those from the Seba collection. They were described again by (1802) in the Mémoire sur l'animal de la Lingule. This memoir was reissued in 1817, the date under which this memoir is usually quoted. In 1802 (republished in 1824 and 1836), too described Lingula anatina in his "Histoire naturelle des coquilles" (Fig. 8

). Appointed in 1793 at the Muséum de Paris as a professor on insects and worms, was not as skilled as in making detailed analyses, so he gave easy access to his specimens, in particular those from the Seba collection. They were described again by (1802) in the Mémoire sur l'animal de la Lingule. This memoir was reissued in 1817, the date under which this memoir is usually quoted. In 1802 (republished in 1824 and 1836), too described Lingula anatina in his "Histoire naturelle des coquilles" (Fig. 8 ![]() ).

).

The origin of the species name is unknown, but in Latin the adjective anatinus, a, um, means "duck or belonging to the duck" perhaps because a resemblance to the "bec de cane" (female duck bill) as indicated by (1798; Fig. 1 ![]() ) for the Lingula shell? (1758) had defined it in a few words "d'une espèce particulière de conque anatifère" (quoted by , 1802, p. 2; Fig. 2

) for the Lingula shell? (1758) had defined it in a few words "d'une espèce particulière de conque anatifère" (quoted by , 1802, p. 2; Fig. 2 ![]() ). The French word anatifère is composed of the Latin

radical anas, anatis (meaning "duck") and the suffix -fère (from the Latin -fer "which carries") - see "Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé" (A.T.I.L.F., 2007). Note that Goose barnacle is Anatife in French (see , 1801; and Fig. 7

). The French word anatifère is composed of the Latin

radical anas, anatis (meaning "duck") and the suffix -fère (from the Latin -fer "which carries") - see "Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé" (A.T.I.L.F., 2007). Note that Goose barnacle is Anatife in French (see , 1801; and Fig. 7 ![]() ).

).

Lingula anatina was recognized as the type species of the genus Lingula only late in 1892 (see , 1964; , 1982, 1985). Yet G.B. (1847) had already attributed the genus Lingula to and the type species L. anatina to . In addition, he listed the current extant species: Lingula anatina , 1801; L. hians , 1823, [now L. rostrum (, 1798)]; L. audebarti , 1835 [now Glottidia audebarti]; L. semen , 1835 [now Glottidia semen (, 1835) ]; L. tumidula , 1841; L. ovalis , 1841 [now L. reevii , 1880]; L. albida , 1841 [now Glottidia albida].

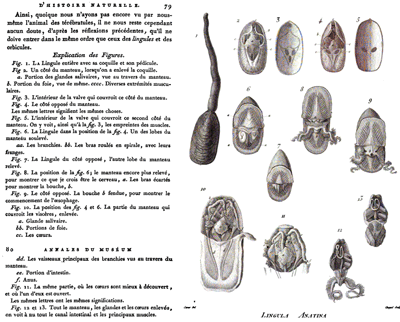

(1888) introducing the family Lingulidae wrote: "The recent species belonging to this family are representatives of the genus Lingula, (1789), and to the genus or subgenus Glottidia, (1870)". And he attributed Lingula anatina to , 1819 on the list of Lingula species, but to in the species description (Fig. 4 ![]() ).

).

(2000) in an analysis of 's text (1819) wrote: "En ce qui concerne les Lingules, ne retient que la lingule actuelle, Lingula anatina, qui habite l'Océan des Moluques" (p. 258). But he added: "l'animal de la térébratule est fort rapproché de celui de la lingule par ses rapports" (p. 244). (1802) also compared Lingula with Terebratula and on p. 9 in discussing the craniid now named Novocrania anomala (, 1776) he wrote: "Il suffit de jeter les yeux sur la figure que a donnée de l'animal de son Patella anomala, pour voir qu'il ressemble à la lingule par des bras ciliés et en spirale".

I could not find the origin of the adjective linguliform. However, the earliest definition is in (1859, p. 260): linguliform, tongue shaped. This descriptive term is employed in a specific scientific sense in several groups of invertebrates (crustaceans, brachiopods), and in botany and medicine. As concerns brachiopods it appeared in the 1880's.

Linguliform means having the form of a tongue, tongue-shaped. It is derived from the Latin linguliformis. et alii (1834) used it for Mytilus describing "the linguliform of the appendage of the foot". More interesting is that this adjective was not used in the description of Lingula in the same book (p. 131) in which Lingula anatina is attributed to .

At the beginning of his memoir of 1802 was the first to discuss the shape of the shell but these sentences have not been heeded:

"Il n'est pas de genres de testacés qui prouve mieux que ne fait celui des Lingules, la nécessité de connoître [= connaître] l'animal, et ne pas se borner à la coquille, pour ranger convenablement ces mollusques dans une méthode naturelle.

En effet les coquilles des Lingules, quoique de forme assez particulière, ne pouvoient [= pouvaient] faire soupçonner les grandes différences qui séparent leur animal des autres genres de sa classe ; et tant qu'on n'a connu qu'elles, on les a ballottées arbitrairement de genre en genre."

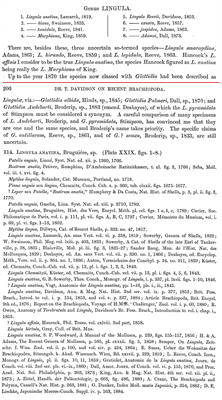

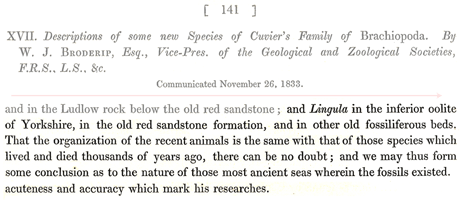

From the Jurassic of Great-Britain came the first descriptions of fossil lingulides, i.e., Lingula mytilloides, L. ovalis, L. tenuis. They were made by

J. (1812; Fig. 9 ![]() ) based on 's (1758) and 's (1802) studies and on similarity in the shape of the shell with those of the living species of Lingula. Lingula mytilloides at least is assignable to Lingularia & ,

1993. (1835) was probably the first who affirmed the similarity between fossil and recent forms (Fig. 10

) based on 's (1758) and 's (1802) studies and on similarity in the shape of the shell with those of the living species of Lingula. Lingula mytilloides at least is assignable to Lingularia & ,

1993. (1835) was probably the first who affirmed the similarity between fossil and recent forms (Fig. 10 ![]() ). However the two Lingula species he described were later referred to Glottidia.

). However the two Lingula species he described were later referred to Glottidia.

In the 1840's the similarity of the linguliform shell in extant and fossils forms was emphasized during the studies of the "Lingula flags" in the lower Palaeozoic of North Wales, particularly of those from the Cambrian (see , 1847). In 1845, wrote about the occurrence of Lingula in the "Potsdam sandstone" (New York): "(...) it is highly interesting that one of its commonest organic remains should belong to a living genus (Lingula), and that its form should come very near to species now existing." (p. 132).

Many works and books published between 1845 and 1865 discuss or describe this genus. Consequently the number of species of Palaeozoic Lingula grew rapidly. In various French and English publications during the second half of the XIXth century the geological range of Lingula: "Palaeozoic to Present" is found. (, 1910, p. 29): "Dans les couches les plus inférieure des terrains primaires, on trouve des lingules, tout à fait semblables aux lingules des mers actuelles (fig. 27 et 28); c'est là un premier exemple de longévité extraordinaire de certains types d'animaux". Consequently, based solely on the shape of the shell any fossil linguliform brachiopod was assigned this genus! However, (1982, 2002), and (1993) have demonstrated that this shape has no taxonomic value. The linguliform shape also occurs in several other inarticulated brachiopod families, i.e., the Pseudolingulidae, Obolidae, and Eoobolidae, of which many species were originally referred to the genus Lingula.

The broad geological range and the similarity in the shape of the lingulide shell throughout the Phanerozoic led (1859) to create the term living fossil for his book "On the Origin of Species" (Table 2 ![]() ), in which several sentences refer to Lingula.

), in which several sentences refer to Lingula.

Since 's times Lingula is considered as in an almost unchanged form since first appearing in the Cambrian period around 550 MA ago. Once found in more widespread environments, today's Lingula are confined to brackish intertidal habitats where they live in burrows. Such a statement concerning persistence is known to be wrong (see , 1997). The taxa of the superfamily Linguloidea show morphological evolutionary changes despite the panchronic characteristics of this group among the Recent Brachiopods. Consequently, 's statement that Lingula is a "living fossil" must be rejected (see , 2003).

Today this anachronism, condemned for more than two decades and blatantly erroneous for those who work on evolution, can still be read on Web sites and in publications. Some recent examples among others:

et alii (1996) created a new subphylum of Brachiopoda named "Linguliformea" which includes all the former Inarticulata Brachiopoda, except the former Craniida which become the subphylum Craniiformea. Linguliformea appears to be inappropriate as the name for a group of which the majority of taxa do not have a linguliform shell.

and (2003) write: "Lingula. Linguliform brachiopod. Ordovician-Recent. A small (about 2 cm from the beak to the anterior edge), smooth, phosphatic brachiopod known as a "living fossil" as its morphology has not changed significantly since the Ordovician. Fully infaunal, it lives in burrows with its anterior edge close to the sediment-water interface. The pedicle anchors the brachiopod to the mud whilst the valves rotate and grind through the sediment. Modern Lingula mainly exploit marginal habitats, but fossil Lingula are known from shelf and basin environments." NB: Lingulide species may reach 7-8 cm, are unable to live in a muddy substrate, but live in true marine conditions and habitats (, 1986, 1997)

J. (2006): "Living fossils: this is a potentially confusing description of animals that have changed remarkably little over long periods of time. Examples include brachiopod Lingula, found in Cambrian fossils and persisting today." So the confusion is maintained.

As a result of this blind consensus even today fossil linguliform brachiopods are assigned the genus Lingula based only on their linguliform appearance. Nevertheless, this scientific anachronism has been impugned for over two decades by (1982, 1997, 2002), and (1993). These authors have demonstrated as pointed out two centuries ago by (1802) that the shape of the lingulide shell is not a taxonomically valid character. The concept introduced by that Lingula is a "living fossil" must be rejected (see , 2003).

The persistence of this scientific heresy may be related to the conservatism of the palaeontological community. A partial explanation is contained in the answer of an American specialist in Mesozoic brachiopods, who in 2003 wrote me in an email: "(...) people who study faunal lists and databases instead of anatomy and taxonomy, and thus perpetuate older nomenclature. As the ecology and distribution of lingulides does not seem to have changed dramatically since their origin, the name "Lingula" has a tremendous amount of inertia."

An anonymous referee, an Anglophone palaeontologist (according to the editor of the Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology) in 1982 wrote this short sentence as comment on my submittal to that journal: "All what is written in this manuscript is opposite of what can be read on Lingula in any treatise of palaeontology. To be rejected". My work was published in Marine Biology (, 1983).

Evidence of an approach to the acceptance of the possibility that linguliform brachiopods are not all assignable to a single unique genus is found in the successive editions of the Treatise of Invertebrate Paleontology. In the first (R.C. , 1965) the stratigraphic distribution of Lingula was: "? Ord., Sil.-- Rec., Cosmopolitan." The 2nd edition ( and , 2000) states: "?Cretaceous, Tertiary-Holocene;? Cosmopolitan (exact stratigraphic and geographic distribution of fossil forms is very uncertain)". The study of these distributions has advanced considerably ( et alii, 2001; , 2003; and , 2005; and , 2008) but no update regarding them was made in the revision of and 's contribution in the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology: Volume 6 (2007) part H, Brachiopoda.

Finally, in the future may authors stop using the so-easy copy and paste, and instead read recent papers on the matter.

Many of the works quoted here are available on the Web, e.g., http://darwin-online.org.uk/ - http://www.lamarck.cnrs.fr/ - http://www.buffon.cnrs.fr/ - http://www.literature.org/ - http://books.google.com/ - Universal Bibliophiles Association: http://abu.cnam.fr/ (more at http://paleopolis.rediris.es/BrachNet/ANNONCES/JOURNAL/e-library.html). I would like thank Martin of Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen (http://www.sub.uni-goettingen.de/ - http://www.animalbase.uni-goettingen.de/zooweb/servlet/AnimalBase/search) and of the Zentrum Göttinger Digitalisierung (GDZ: http://gdz.sub.uni-goettingen.de/) for permission to reproduce some of facsimiles made available on these sites. I am most grateful to Remy and to two anonymous referees for comments on the earlier version, and to Nestor for improvements in the English of this version.

1 and are the founders of the science of palaeontology, both vertebrate and invertebrate (see , 2000). also created the word "biology" for the science of living beings.

2 In conventional terminology "lingulid" designates taxa or specimens of the Order Lingulida; preferably this word should now be restricted to indicate members of the superfamily Linguloidea. And the term, "lingulide" is used to indicate taxa and specimens of the family Lingulida.

A.T.I.L.F. - Analyse et Traitement Informatique de la Langue Française (2007).- Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé (Le).- C.N.R.S., http://atilf.atilf.fr/

R. (1982).- Compte rendu sur les datations de Bernard , Datations et documents lexicographiques.- Revue de Linguistique romane, Paris, vol. 46, p. 453-461. [Lingula p. 460]

G. & C.C. (1993).- Anatomical distinctions of the Mesozoic lingulide brachiopods.- Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, Warszawa, vol. 38, n° 1, p. 1-20.

M.A. & A. (2008).- Eocene micromorphic brachiopods from north-western Hungary.- Geologica Carpathica, Bratislava, vol. 59, n° 1, p. 31-43.

L.A.G. (1802 = an X).- Histoire naturelle des coquilles, contenant leur description, les mœurs des animaux qui les habitent et leurs usages.- Déterville, Paris, vol. 2. 330 p.

L.A.G. (1836). Histoire naturelle des coquilles contenant leur description, les mœurs des animaux qui les habitent et leurs usages [Lingula: p. 169-172 ; Pls. 45.].- Librairie encyclopédique de Roret, Paris, 3e éd., vol. 1, 539 p.

M. (1910).- Conférences de géologie.- Masson, Paris, 160 p. [p. 29]

W.J. (1835).- Descriptions of some new species of 's family of Brachiopoda.- Transactions of the zoological Society of London, vol. 1, p. 141-144.

J.G. (1791 [1789]).- Tableau Encyclopédique et Méthodique des trois Règnes de la Nature : vers, coquilles, mollusques et polypes divers.- Panckoucke, Paris, T. 1, Pls. 172-344. [Lingula: Pl. 250, fig. 1a-c]

J.G. (ca 1793).- Histoire naturelle des vers.- Panckoucke, Paris, Tableau [2.] Planches 199/488.

J.G. (1797).- Tableau Encyclopédique et Méthodique des trois Règnes de la Nature : vers, coquilles, mollusques et polypes divers.- Panckoucke, Paris. T. 2, Pls. 190-286. [Lingula: Pl. 250, fig. 1a-c]

von J.H. (1786).- Neues systematisches Conchylien-Cabinet. Geordnet und beschrieben von Friedrich Heinrich Wilhelm und unter dessen Aufsicht nach der Natur gezeichnet und mit lebendigen Farben erleuchtet.- Raspe, Nürnberg, vol. 9, n° 2, 194 p., Pls. 1-20.

G. (1798).- Tableau élémentaire de l'histoire naturelle des animaux.- Baudouin, Paris, 710 p., Pls. I-XIV. [Lingula: p. 435]

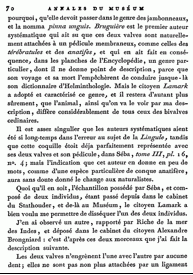

G. (An XI = 1802).- Mémoire sur l'animal de la Lingule (Lingula anatina ).- Annales du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris, vol. 1, p. 69-80, Pl. VI.

G. (1817).- Mémoire sur l'animal de la Lingule (Lingula anatina ). In: Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire et à l'anatomie des Mollusques.- Déterville, Paris, 489 p. [12 p.]

G. & P.A. (1817).- Le règne animal distribué d'après son organisation pour servir de base à l'histoire naturelle des animaux et d'introduction à l'anatomie comparée.- Déterville, Paris, t. 2, 406 p.

G., E., C.H., E., J.E., P.A. & G.R. (1834).-The animal kingdom arranged in conformity with its organization.- Whittaker, London, Vol. 12.

C.R. (1859).- On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life.- Murray, London, 1st edition, 1st issue, 502 p.

T. (1880).- Report on the Brachiopoda dredged by the HMS Challenger during the years 1873-1876.- Report of the Scientific Research of the Voyage of the HMS Challenger, London, vol. 1, n° 1, p. 1-67, Pls. 1-4.

T. (1888).- A monograph of the Recent Brachiopoda. Part III.- Transactions of the Linnean Society of London, (2) vol. 4 (Zool.), p. 205-230.

A.M.C. (1806).- Zoologie analytique, ou méthode naturelle de classification des animaux, rendue plus facile à l'aide de tableaux synoptiques.- Allais, Paris, 344 p. [Brachiopoda p. 171]

C.C. (1982).- Taxonomie du genre Lingula (Brachiopodes, Inarticulés).- Bulletin Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle de Paris, (4) vol. 4 (Sect. A) (3/4), p. 337-367.

C.C. (1983).- Comportement expérimental de Lingula anatina (Brachiopode, Inarticulé) dans divers substrats meubles (Baie de Mutsu, Japon).- Marine Biology, Berlin, vol. 75, n° 2/3, p. 207-213.

C.C. (1986).- Conditions de fossilisation du genre Lingula (Brachiopoda) et implications paléoécologiques.- Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, Amsterdam, vol. 53, p. 245-253.

C.C. (1997).- Ecology of inarticulated brachiopods - Biogeography of inarticulated brachiopods. In: R.L. (ed.), Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part H, Revised, Brachiopoda.- Geological Society of America and University of Kansas, Boulder, Colorado, and Lawrence, Kansas, vol. 1, p. 473-502.

C.C. (2002).- Tools for linguloid taxonomy: the genus Obolus (Brachiopoda) as an example.- Carnets de Géologie/Notebooks on Geology, Article 2002/01 (CG2002_A01), 9 p., 3 figs., 2 tabl.

C.C. (2003).- Proof that Lingula (Brachiopoda) is not a living-fossil, and emended diagnoses of the Family Lingulidae.- Carnets de Géologie/Notebooks on Geology, Letter 2003/01 (CG2003_L01), 8 p., 7 figs., 1 tabl.

C.C. & M.A. (2005).- The brachiopod Lingula in the Middle Miocene of the Central Paratethys.- Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, Warszawa, vol. 50, n° 1, p. 181-184.

C.C. & P. (1979).- Lingules d'Amboine, Lingula reevei et Lingula rostrum (), données écologiques et taxonomiques concernant les problèmes de spéciation et de répartition.- Cahiers de l'Indo-Pacifique, Paris, vol. 2, p. 153-164.

N.L. (2003).- Dating and publication of the Encyclopédie Méthodique (1782-1832), with special reference to the parts of the Histoire Naturelle and details on the Histoire Naturelle des Insectes.- Zootaxa, Paris, vol. 166, p. 1-48.

N.L. & R.E. (2003).- Corrections and additions to the dating of the "Histoire Naturelle des Vers" and the Tableau Encyclopédie (Vers, coquilles, mollusques et polypiers) portions of the Encyclopédie Méthodique.- Zootaxa, Paris, vol. 207, p. 1-4.

J.F. (1789).- Systema Naturae, editio decima tertia aucta.- Reformata I. Ps. VI. Vermes. Lipsiae. p. 3021-4120.

L. (2000).- Paléontologie(s) et évolution au début du XIXe siècle et .- Asclepio, Madrid, vol. 52, p. 133-212.

B. (1888).- Lehrbuch der Zoologie, eine morphologische Übersicht des Thierreiches zur Einführung in das Studium dieser Wissenschaft.- Fischer, Jena, 432 p.

L.E. & L.E. (2000).- Class Lingulata. In: R.L. (ed.), Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part H. Revised Brachiopoda.- Geological Society of America, Boulder, and University of Kansas, Lawrence, Vol. 2, p. 30-146.

L.E. & L.E. (2007).- Linguliformea. In: R.L. (ed.), Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part H. Revised Brachiopoda.- Geological Society of America, Boulder, and University of Kansas, Lawrence, Vol. 6, p. 2532-2559.

- International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (1982).- Lingula anatina , 1801 (Brachiopoda), proposed conservation. Z.N. (S.) 1598.- Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature, London, vol. 139, p. 302-304.

- International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (1985).- Opinion 1355. Lingula anatina , 1801 is the type species of Lingula , [19797] (Brachiopoda).- Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature, London, vol. 42, p. 332-334.

E.A. (1965).- The Reverend John , Daniel , and the Portland Catalogue.- The Nautilus, Sanibel, vol. 79, n° 1, p. 10-19.

J. (1859).- The Microscopist's Companion; a popular manual of practical microscopy: To which is added a glossary of the principal terms used in microscopic science.- Rickey, Mallory & Co., 308 p.

J.B. [P.A. de de] (1801).- Système des animaux sans vertèbres, ou tableau général des classes, des ordres et des genres de ces animaux, présentant leurs caractères essentiels et leur distribution, d'après la considération de leurs rapports naturels et de leur organisation, et suivant l'arrangement établi dans les galeries [sic!] du Muséum d'Hist. Naturelle, parmi leurs dépouilles conservées; précédé du discours d'ouverture du Cours de Zoologie, donné dans le Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle l'an 8 de la République.- Déterville, Paris, 432 p., Pls. 1-6. [Lingula p. 140-141]

J.B. [P.A. de de] (1819).- Histoire naturelle des Animaux sans vertébres.- Déterville, Paris, vol. 6, n° 1, 586 p. [Brachiopoda p. 240-258].

J. (1786).- A catalogue of the Portland Museum, lately the property of the Duchess of Portland, deceased; which will be sold at auction, by Mr. and Co. on Monday the 24th of April, 1786.- Skinner, London, 194 p.

C. (1758).- Systema naturea per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis.- Salvius, Stockholm, vol. 1, Editio decima, reformata, 824 p. [Lingula: p. 783]

C. von (1767).- Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis.- Salvius, Stockholm, vol. 1., n° 2, Editio duodecima reformata, p. 533-1327. [Lingula: p. 1260]

C. (1845).- Travels in North America in the years 1841-2; with geological observations on the united states, Canada, and Nova Scotia.- Wiley and Putnam, New-York, Vol. 1, 232 p.

C.T. (1828).- Synopsis methodica molluscorum generum omnium et specierum earum, quae in museo Menkeano adservantur; cum synonymia critica et novarum specierum diagnosibus.- Uslar G., Pyrmonti, Uslar, 91 p.

C. & S. (2003).- Fossils at a glance.- Blackwell Science, Oxford, 155 p. [Lingula: p. 40]

J. (2006).- An introduction to the Invertebrates.- Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2nd ed., 338 p. [Lingula: p. 15]

R.C. (ed.) (1965).- Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part H. Brachiopoda.- Geological Society of America, Boulder, and University of Kansas, Lawrence, 927 p.

H.L. (1955).- A history of the classification of the phylum Brachiopoda.- British Museum (Natural History), London, 124 p.

R.I. (1847).- A brief review of the classification of the sedimentary rocks of Cornwall.- Edinburgh new Philosophical Journal, vol. 43, p. 33-40.

I., R. & J. (2005).- A.: Das Naturalienkabinett. Vollständige Ausgabe der kolorierten Tafeln 1734 - 1765.- Taschen, Allemagne, 587 p.

d' A. (1852).- Cours élémentaire de paléontologie et de géologie stratigraphiques.- Masson, Paris, 382 p.

B. (1982).- Datations et documents lexicographiques: Collection Matériaux pour l'histoire du Vocabulaire français.- Klincksieck, Paris, vol. 20, 254 p.

A.J. (1964).- Lingula (1797) (Brachiopoda, Inarticulata): proposed designation of a type-species under the plenary powers. Z. N. (S.) 1598.- Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature, London, vol. 21, p. 222-224.

G.E. (1705).- D'Amboinsche rariteitkamer: behelsende een kort verhaal der gedenkwaardigste geschiedenissen zo in vreede als oorlog voorgevallen sedert dat de Nederlandsche Oost Indische.- Halma, Amsterdam, 340 p.

P.H., M. & A. (2001).- Hypoxic events on a Middle Miocene carbonate platform of the Central Paratethys (Austria, Badenian, 14 Ma).- Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien, (A), vol. 102, p. 1-50.

A. (1758).- Locupletissimi rerum naturalium thesauri accurata descriptio et iconibus artifi ciosissimus expressio per universam physices historiam.- Janssonius van Waesberge, Amsterdam, vol. 3, 511 p., 116 Pls. [Lingula: Pl. 16, fig. 4].

A., G., A.G., J.G. & F.E. (1828).- Planches de , Locupletissimi Rerum naturalium Thesauri accurata Descriptio. Accompagnées d'un texte explicatif mis au courant de la Science.- Levrault, Paris, vol. 3.

C.D. & B.B. (1906).- On the dates of publication of the natural history portions of the "Encyclopédie Méthodique".- Annals and Magazine of Natural History, London, (ser. 7), vol. 17, p. 577-582.

D.C., manuscrits non publiés, in (1786): Mytilus lingua, p. 77, no. 1718.

G.B. (1847).- Thesaurus conchyliorum or Monographs of genera of shells.- Sowerby, London, vol. 1, 438 p., 91 Pls. [Lingula: p. 337-339, Pl. 57]

J. (1812).- The mineral conchology of Great Britain, printed by B. Meredith, London, vol. 1, 244 p. [Lingula: p. 55-56, Pl. 19, figs. 1-4]

A., S.J., C.H.C., L.E. & L. (1996).- A supra-ordinal classification of the Brachiopoda.- Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, B, vol. 351, p. 1171-1193.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image

Figure 3: (1802): p. 79 and 80, Pl. VI.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image

Figure 4: (1888): part of p. 205 and 206.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image

Figure 6: (1758): fig. 4 - detail of plate 15.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image

Figure 7: (1801): p. 140 and 141.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image

Figure 8: (1802): p. 172 and Pl. 45.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image

Figure 9: J. (1812): Pl. 19 - f. 1 & 2: Lingula mytilloides; f. 3: L. tenuis; f. 4 L. ovalis.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge the image

| NAME and surname | Years | Nationality |

| Albert ou Albertus | 1665 - 1736 | German, lived in Amsterdam |

| Karl - Carl von after his ennoblement in 1762 | 1707 - 1778 | Swedish |

| , Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de , Chevalier de - | 1744 - 1829 | French |

| Jean Guillaume | 1750 - 1798 | French |

| James | 1757 - 1822 | British |

| , Baron Georges Léopold Chrétien Frédéric Dagobert | 1769 - 1832 | French |

| George Brettingham | 1788 - 1854 | British |

| Charles | 1809 - 1882 | British |

| Thomas | 1817 - 1885 | British |

Table 1: Dates et origin of the main authors who published the early works on the Lingula.

| (1859) | Original text | Texte en français |

| p. 107 Chapter 4 |

And it is in fresh water that we find seven genera of Ganoid fishes, remnants of a once preponderant order and in fresh water we find some of the most anomalous forms now known in the world, as the

Ornithorhynchus and Lepidosiren, which, like fossils, connect to a certain extent orders now widely separated in the natural scale. These anomalous forms may almost be called living fossils; they have endured to the present day, from having inhabited a confined area, and from having thus been exposed to less severe competition.

|

Or, c'est dans l'eau douce que nous trouvons sept genres de poissons ganoïdes, restes d'un ordre autrefois prépondérant ; c'est également dans l'eau douce que nous trouvons quelques-unes des formes les plus anormales que l'on connaisse dans le monde, l'Ornithorhynque et le Lépidosirène, par exemple, qui, comme certains animaux fossiles, constituent jusqu'à un certain point une transition entre des ordres aujourd'hui profondément séparés dans l'échelle de la nature. On pourrait appeler ces formes anormales de véritables fossiles vivants ; si elles se sont conservées jusqu'à notre époque, c'est qu'elles ont habité une région isolée, et qu'elles ont été exposées à une concurrence moins variée et, par conséquent, moins vive.

|

| p. 307 Chapter 9 |

Some of the most ancient animals, as the Nautilus, Lingula, etc., do not differ much from living species, and it can not on my theory be supposed, that these old species were the progenitors of all the species of the orders to which they belong, for they do not present characters in any degree intermediate between them.

|

Quelques-uns des animaux les plus anciens, tels que le Nautile, la Lingule, etc., ne diffèrent pas beaucoup des espèces vivantes ; et, d'après ma théorie, on ne saurait supposer que ces anciennes espèces aient été les ancêtres de toutes les espèces des mêmes groupes qui ont apparu dans la suite, car elles ne présentent à aucun degré des caractères intermédiaires.

|

| p. 313 Chapter 10 |

Species of different genera and classes have not changed at the same rate, or in the same degree. In the oldest tertiary beds a few living shells may still be found in the midst of a multitude of extinct forms. The Silurian

Lingula differs but little from the living species of this genus; whereas most of the other Silurian Molluscs and all the Crustaceans have changed greatly.

|

Les espèces appartenant à différents genres et à différentes classes n'ont pas changé au même degré ni avec la même rapidité. Dans les couches tertiaires les plus anciennes on peut trouver quelques espèces actuellement vivantes, au milieu d'une foule de formes éteintes. La lingule silurienne diffère très peu des espèces vivantes de ce genre, tandis que la plupart des autres mollusques siluriens et tous les crustacés ont beaucoup changé.

|

| p. 316 Chapter 10 |

Species of the genus Lingula, for instance, must have continuously existed by an unbroken succession of generations, from the lowest Silurian stratum to the present day.

|

Les espèces du genre lingule, par exemple, qui ont successivement apparu à toutes les époques, doivent avoir été reliées les unes aux autres par une série non interrompue de générations, depuis les couches les plus anciennes du système silurien jusqu'à nos jours.

|

| p. 331 Chapter 10 |

The Silurian

Lingula differs but little from the living species of this genus; whereas most of the other Silurian Molluscs and all the Crustaceans have changed greatly.

|

La lingule silurienne diffère très peu des espèces vivantes de ce genre, tandis que la plupart des autres mollusques siluriens et tous les crustacés ont beaucoup changé.

|

Table 2: References to Lingula and living fossils in 's book (1859): in original version, and translated into French by http://abu.cnam.fr/cgi-bin/go?espece1 (Copyright © 1999 Association de Bibliophiles Universels http://abu.cnam.fr/)