Histoires de Brachiopodes Brachs' Stories |

|---|

|

| Comment les Brachiopodes Lingulidés ont fait céder l'URSS ! |

|

L'exploitation des grès phosphatés ou phosphorites du Cambrien1, situés dans le Nord-Est de l'Estonie, a débuté en 1924 pour les besoins de l’agriculture. Après l'occupation soviétique en 1940, leur exploitation industrielle commença. Au cours des années 1980, Moscou voulu accroître l'effort minier et entrepris une étude intensive par carottage dans toute la région, ce qui provoqua de la part de la population este des vagues de fortes protestations, dès 1987, contre le creusement de nouvelles mines. Ce fut la "guerre des phosphorites", qui donna naissance au "Mouvement du Front Populaire" contre le régime soviétique. Ces actions aboutirent à l'indépendance de l'Estonie prononcée en 1991 ! Et toutes les mines furent fermées en 1992. Pas beaucoup de groupes zoologiques peuvent se vanter d'avoir fait plier une superpuissance (à l'époque) pour "délivrer” un peuple de quelque 1,5 M d’habitants ! 1 Le phosphate provient exclusivement des coquilles des brachiopodes lingulides des genres Obolus (sensu stricto), Ungula, Schmidtites, Oepikites. De ces couches aurait aussi été extrait l'uranium de la première bombe nucléaire soviétique! | |

|

How Lingulid Brachiopods made the USSR yield! | |

|

Exploitation, mainly for agricultural purposes, of the phosphatic sandstones, “phosphorites”, from the Cambrian1 of northeastern Estonia began in 1924. Their exploitation on an industrial scale commenced only in 1940 after the Soviet occupation. During the 80’s the USSR decided to expand its mining effort and undertook an extensive coring program. This caused waves of protest against the new quarries by the Estonians. That was the beginning of the “phosphorite war” which gave birth to the “Popular Front Movement” against the Soviet regime. In the end its activities led to the independence of Estonia in 1991. And in 1992 all of the mines were closed. There are not many zoological groups that can boast of having delivered a country of 1.5 million inhabitants from occupation by one of the two Great Powers. 1 The phosphate comes exclusively from the shells of lingulid brachiopods belonging to the genera Obolus (sensu stricto), Ungula, Schmidtites, Oepikites. Uranium for the first Soviet nuclear bomb would also have been extracted from these phophorite layers. |

Middle Devonian brachiopods Stringocephalus gubiensis in life position – the bottom of a brachiopod bed from the Gi- vetian of Guangxi - Fossil shop in Guilin. Photos by A.T. Halamski |

Les Brachiopodes dans la Médecine Traditionnelle Chinoise |

|

Les Chinois broyaient et broient encore des « papillons de pierre » qui ne sont que des spirifers (brachiopodes fossiles paléozoïques) pour soigner plusieurs affections qui n’ont aucun lien entre elles. Ces spirifers sont appelés Shiy Yen, ce qui signifie « pierre à avaler ». Broyées et cuites dans un pot d’argile, ils sont sensés soigner rhumatisme, cataracte, anémie, problèmes digestifs etc. Remarques - voir Rong et al., 2004, pp. 828-829 : de nombreux exemplaires de brachiopodes appartenant aux genres Atrypa, Athyrisina, Cyrtospirifer, Yangzteella, entre d'autres, ont été récoltés par des gens du pays dans divers endroits du Sichuan, Hunan, Hubei, et d'autres provinces chinoises, pour être vendus à des pharmacies, pour faire des préparations de la médecine chinoise. Pendant des siècles, et encore de nos jours, ils sont ramassés et mis en suspension dans de l'eau chaude, une boisson servant à refroidir la température du corps. Aussi, n'était-il pas rare de pouvoir acheter des beaux brachiopodes fossiles dans une pharmacie pour, par exemple, les étudier, comme le remarque Grabau (1931, p. 515). Ainsi, il semble raisonnable de penser que les exemplaires d'Athyrisina squamosa étudiés par Hayasaka (1922) pourrait avoir été achetés dans une pharmacie, plutôt que collectés sur le terrain, et ceci pourrait être à l'origine de données incorrectes, tant géographiques que stratigraphiques, sur les exemplaires de cet auteur. Références Grabau A.W., 1931. The Permian of Mongoilia. American Museum of Natural History, Natural Historyof Central Asia, 4, 1-665. Halamski A.T., 2016. Seventh International Brachiopod Congress Nanjing, China, 22-25 May 2015. http://paleopolis.es/BrachNet/REF/Pub/Halamski-2016.html Hayasaka, I. (1922). Palaeozoic Brachiopoda from Japan, Korea and China. Part 1. Middle and south China. Sci. Rep. Tokôhu Imp. Univ., Ser. 2, Geology, 6, 1-109. Rong J., Álvarez F., Modzalevskaya T. L. & Y. Zhang, 2004. Revision of the Athyrisininae, Siluro-Devonian brachiopods from China and Russia. Palaeontology, 47, 811-857. | |

|

Brachiopods in Traditional Chinese Medicine | |

|

Traditionally fossils are said to have supernatural powers, healing powers and medicinal uses. In Traditional Chinese Medicine, fossilised brachiopods named Shiy-Yen are prepared as a cure for rheumatism, cataracts, anaemia and digestive problems. Remarks (see Rong et al., 2004, pp. 828-829): a large number of brachiopod specimens belonging to Atrypa, Athyrisina, Cyrtospirifer, Yangzteella and other genera were collected by locals and sold to drug stores, to prepare Chinese medicine, in many places in Sichuan, Hunan, Hubei and other Chinese provinces. For centuries, and to this day, they are ground up and put into suspension in hot water as a drink for cooling down the body. Hence, it was not uncommon to purchase from a drug store good specimens for study as, for example, did Grabau (1931, p. 515). Thus, it seems reasonable to think that the specimens of Athyrisina squamosa studied by Hayasaka (1922) might have been obtained from a drug store, rather than been collected in the field, and that this could be the origin of incorrect, geographical and stratigraphical data on type his specimens. References Grabau A.W., 1931. The Permian of Mongoilia. American Museum of Natural History, Natural Historyof Central Asia, 4, 1-665. Halamski A.T., 2016. Seventh International Brachiopod Congress Nanjing, China, 22-25 May 2015. http://paleopolis.es/BrachNet/REF/Pub/Halamski-2016.html Hayasaka, I. (1922). Palaeozoic Brachiopoda from Japan, Korea and China. Part 1. Middle and south China. Sci. Rep. Tokôhu Imp. Univ., Ser. 2, Geology, 6, 1-109. Rong J., Álvarez F., Modzalevskaya T. L. & Y. Zhang, 2004. Revision of the Athyrisininae, Siluro-Devonian brachiopods from China and Russia. Palaeontology, 47, 811-857. |

|

Nota : les phrase soulignées en gras sont de ma main pour mettre en exergue celles traitant directemenrt de brachiopodes. Elles sont traduites en anglais ci-dessous. (Christian Emig) |

Les Brachiopodes dans les |

|

p. 34-35 (1) Diego de Torres (1637), Histoire des Chérifs, p. 312. p. 394 p. 602 |

|

|

Brachiopods in the Magic and Beliefs of the Maghreb |

|

| Nota : the sentences in front are the tranlation of the bold ones in the text in French above. |

p. 34-35 p. 394 p. 602 |

|

Les Brachiopodes et les créationnistes |

|

Lingula est considérée comme un modèle par les créationnistes : quelque 13 000 pages web apparaissent à une interrogation avec Google | |

|

Brachiopods and creationnists | |

|

Lingula is used as model by the creationists : About 13 000 Web is the result of a Google search.

|

|

Shamisen-gai = Lingula |

|

Le shamisen est une sorte de luth (de 1,10m à 1,40m) à caisse de résonance carrée traditionnellement construite en bois de santal et recouverte de peau de chat ou de chien. Il possède trois cordes (d'où son nom, trois cordes du goût) de soie ou de nylon. A cause de la similitude de forme, le nom vernaculaire des Lingula est shamisen-gai au Japon. L'espèce la plus commune est L. anatina. | |

|

Shamisen-gai = Lingula | |

|

The shamisen, also called sangen (literally "three strings") is a three-stringed musical instrument played with a plectrum called a bachi. Its drum-like rounded rectangular body made of santal wood is covered front and back with skin usually from a dog or cat. The shamisen is similar in length to a guitar, between 1.10m to 1.40m. The three strings are traditionally made of silk, or, more recently, nylon. The shamisen evolved from the Chinese sanxian, which was originally imported to Japanese islands through Okinawa in the middle of the 16th century. It can be played solo or with other shamisen, with singing such as nagauta, or as an accompaniment to drama, notably kabuki and bunraku. According to the similarity of its general shape, the inarticulated brachiopod Lingula is named shamisen-gai in Japan. The most commun species is L. anatina.

|

|

Des photos par "Google" de...

|

Des Orthidés et des Spiriferidés |

|

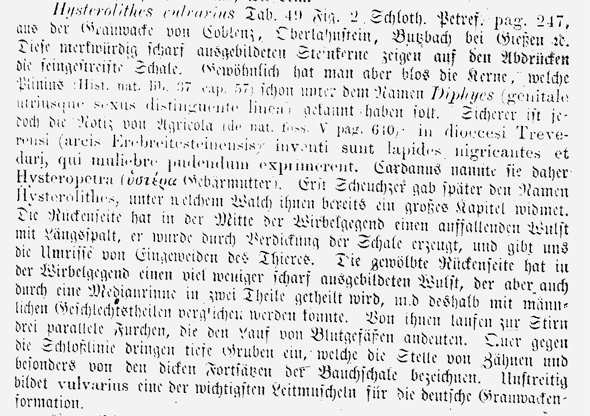

Les relations entre les brachiopodes (orthidés et spiriferidés) et le sexe humain remontent au temps des Romains... "Diphyes duplex, candida ac nigra, mas ac femina"- "genitale utriusque sexus distinguente linea" Ce brachiopode orthide Diphyes deviendra ultérieurement le genre Hysterolithes. « M. la Roche, Médecin, me donna de ces olives pétrifiées, dites lapis Judaïcus, qui croissent en quantité dans ces montagnes, où l’on trouve, à ce qu’on m’a dit, d’autres pierres qui représentent parfaitement au dedans des natures d’hommes & de femmes » Voyage de Monconys, première partie, page 334 ; ceci est l’hysterolithes.  Dies sind Steinkerne von Orthiden und Spiriferiden, die zur Gruppe der Armfüßer (Brachiopoden) gehören und im Erdaltertum (Palöozoikum) verbreitet waren. Eine Klappe dieser Armfüßer besaß eine vulvaähnliche Erhebung. Nach VALENTINI, 1714, soll Hortius, Leibarzt des Landgrafen von Hessen-Darmstadt (1618-1685) aus der Form dieser Versteinerungen geschlossen haben, daß diese gegen Frauenleiden aller Art nützlich seien, und am Arm getragen als Aphrodisiacum wirken sollen. "

Note sur la systématique : Orthidés et Spiriféridés sont pourtant des ordres bien distincts au sein de la

L'ancien genre Hysterolithes von Scholtheim, 1820 a été écrit de différentes façons selon les auteurs, ainsi on peut rencontrer Hysterolithes, Hysterolites, Hysteriolithes. Les orthidés Hysterolithes ont parfois été confondues avec des spiriferidés (voir par ex. Allan, 1942), ce qui ajoute à des confusions au sein de brachiopodes fossiles, quelquefois encore entretenues de nos jours par des paléontologues. La place de Hysterolites vulvarius dans la classification des brachiopodes par Jansen (2001), reprise par Botquelen (2003), est :

Le sous-genre Schizophoria (Pachyschizophoria) a été créé par Jansen (2001). Cet auteur redécrit l'espèce-type Schizophoria (Pachyschizophoria) vulvaria (von Scholtheim, 1820), connue du Dévonien Inférieur en Allemagne, Belgique, Espagne, Maroc, ainsi qu'une nouvelle espèce Schizophoria (Pachyschizophoria) tataensis Jansen, 2001, et deux espèces en nomenclature ouverte Schizophoria (Pachyschizophoria) n. sp. C et n. sp. D., redécrites par Jansen (2001). D'autres espèces de Schizophoria (Pachyschizophoria) sont citées en Allemagne, Pologne, France, Espagne, Maroc, Arabie saoudite. Classées parmi les Spiriferida, d'autres espèces ont été décrites avec des "attributs sexuels" similaires (voir Schemm-Gregory & Jansen, 2005 ; Kaesler, 2006) :

Références Allan R. S., 1942. The Origin of the Lower Devonian Fauna of Reefton, New Zealand; with Notes on Devonian Brachiopoda. Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 72, 144-147 [à télécharger en PDF]. Botquelen A., 2003. Impact des variations eustatiques sur les assemblages benthiques à Brachiopodes : l'Ordovicien Sarde et le Dévonien Ibéro-Armoricain. Thèse Dr. Université de Bretagne Occidentale (Brest), 355 p. [à télécharger en pdf]. Caius Plinius Secundus, 1507. Historiae naturalis, libri XXXVII [à lire à http://gallica.bnf.fr/]. Gruber B., 1980. Fossilien im Volksglauben (als Heilmittel). Katalog Oberösterr. Landesmuseums 105, aussi Linzer Biol. Beiträge, 12 (1), 239-242" [à télécharger en pdf ]. Jansen U., 2001a. Morphologie, Taxonomie und Phylogenie unter-devonischer Brachiopoden aus der Dra-Ebene (Marokko) und dem Rheinischen Schiefergebirge (Deutschland). Abhandlungen der senckenbergischen naturforschenden Gesellschaft, 554, 389 p. [à télécharger extrait en pdf]. Jansen U., 2001b. On the genus Acrospirifer Helmbrecht et Wedekind, 1923 (Brachiopoda, Lower Devonian). Journal of the Czech Geological Society, 46 (3-4), 131-144. [à télécharger en pdf]. Jean Paul, 1797. "Das Kampaner Tal" [à lire à http://freilesen.de/] Kaesler R. L. (ed.), 2006. Rhynchonelliformea (part). Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part H. Brachiopoda Revised. Geological Society of America and University of Kansas. Boulder, Colorado, and Lawrence, Kansas, vol. 5. Leclerc Georges-Louis, Comte de Buffon, (1749). Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière, avec la description du cabinet du Roy. Tome Premier, p. 286 [à lire à http://www.buffon.cnrs.fr/]. Monconys, Balthasar de (1665). Journal des voyages de Monsieur de Monconys, p. 344. Quenstedt F. A., 1867. Handbuch der Petrefaktenkunde. 2. Aufl. Laupp Buchhandl. Tübingen, 1239 pp. [à lire à http://gallica.bnf.fr/]. Schemm-Gregory M. & Jansen U., 2005. Arduspirifer arduennensis treverorum n. ssp., eine neue Brachiopoden-Unterart aus dem tiefsten Ober-Emsium des Mittelrhein-Gebiets (Unter-Devon, Rheinisches Schiefergebirge). Mainzer geowissenschaftliche Mitteilungen, 33, 79-100. Valentini M. B., 1714. Museum Museorum oder vollständige Schaubühne aller Materialien und Specereyen, nebst deren natürlichen Beschreibung, Election, Nutzen und Gebrauch [...]. Frankfurt-am-Main [voir ci-dessus dans Gruber]. Nota : Tous mes remerciement à Mena Shemm-Gregory et Ulrich Jansen pour le droit de reproduire ici leurs figures. |

|

|

On Orthids and Spiriferids | |

In preparation see above French version References Allan R. S., 1942. The Origin of the Lower Devonian Fauna of Reefton, New Zealand; with Notes on Devonian Brachiopoda. Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 72, 144-147 [download PDF]. Botquelen A., 2003. Impact des variations eustatiques sur les assemblages benthiques à Brachiopodes : l'Ordovicien Sarde et le Dévonien Ibéro-Armoricain. Thèse Dr. Université de Bretagne Occidentale (Brest), 355 p. [download pdf]. Caius Plinius Secundus, 1507. Historiae naturalis, libri XXXVII [read at http://gallica.bnf.fr/]. Gruber B., 1980. Fossilien im Volksglauben (als Heilmittel). Katalog Oberösterr. Landesmuseums 105, aussi Linzer Biol. Beiträge, 12 (1), 239-242" [download pdf]. Jansen U., 2001a. Morphologie, Taxonomie und Phylogenie unter-devonischer Brachiopoden aus der Dra-Ebene (Marokko) und dem Rheinischen Schiefergebirge (Deutschland). Abhandlungen der senckenbergischen naturforschenden Gesellschaft, 554, 389 p. [download pdf - partly -]. Jansen U., 2001b. On the genus acrospirifer Helmbrecht et Wedekind, 1923 (Brachiopoda, Lower Devonian). Journal of the Czech Geological Society, 46 (3-4), 131-144. [à télécharger en pdf]. Jean Paul, 1797. Das Kampaner Tal" [read at http://freilesen.de/] Kaesler R. L. (ed.), 2006. Rhynchonelliformea (part). Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part H. Brachiopoda Revised. Geological Society of America and University of Kansas. Boulder, Colorado, and Lawrence, Kansas, vol. 5. Leclerc Georges-Louis, Comte de Buffon, (1749). Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière, avec la description du cabinet du Roy. Tome Premier, p. 286 [read at http://www.buffon.cnrs.fr/]. Monconys, Balthasar de (1665). Journal des voyages de Monsieur de Monconys, p. 344. Quenstedt F. A., 1867. Handbuch der Petrefaktenkunde. 2. Aufl. Laupp Buchhandl. Tübingen, 1239 pp. [read at http://gallica.bnf.fr/]. Schemm-Gregory M. & Jansen U., 2005. Arduspirifer arduennensis treverorum n. ssp., eine neue Brachiopoden-Unterart aus dem tiefsten Ober-Emsium des Mittelrhein-Gebiets (Unter-Devon, Rheinisches Schiefergebirge). Mainzer geowissenschaftliche Mitteilungen, 33, 79-100. Valentini M. B., 1714. Museum Museorum oder vollständige Schaubühne aller Materialien und Specereyen, nebst deren natürlichen Beschreibung, Election, Nutzen und Gebrauch [...]. Frankfurt-am-Main [see above in Gruber]. |

|

Skånes landskapsvapen

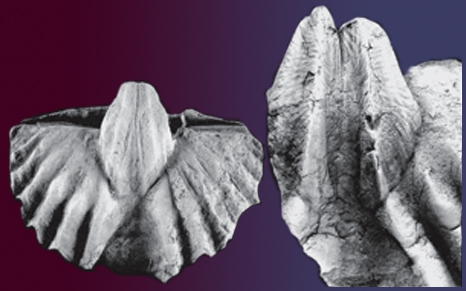

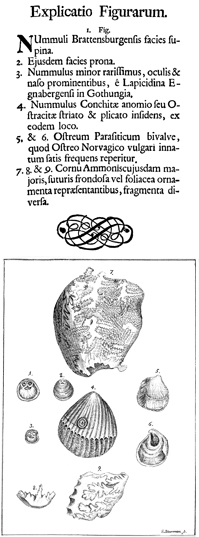

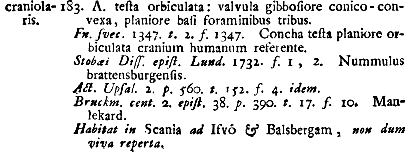

Facsimile des p. 25 et 26 de Stobæus (1732) Explanation of the Figure 1. Small money of Brattensburg reverse face (supina=bend backwards)

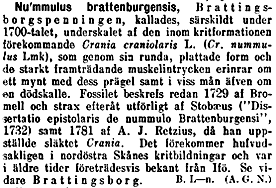

Crania craniolaris

|

Crania craniolaris et la légende des Brattingsborgspenningen |

|

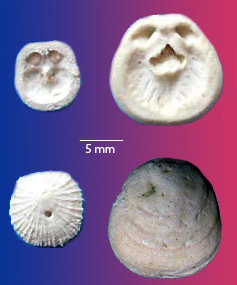

Les pièces de monnaie de Brattinsborg – les fameux Brattingborgspenningarna - sont des valves (ventrales) du brachiopode fossile Crania craniolaris, qui ressemblent à des pièces de monnaie avec tête-de-mort sur une des faces, et dont la célébrité populaire et légendaire commence avec les temps médiévaux dans l'île d'Ivö (ou Ovö) sur le lac Ivö (Ivösjön), en Scanie (Suède). Les Brattingborgspenningarna populaires Il y a beaucoup de légendes au sujet de « Brattingsborgspengarna ». En voici deux qui se racontent encore de nos jours en Scanie. Celles-ci, nous les devons à Ida Fredriksson du « Bromölla Turistkontor » qui a eu la gentillesse de nous les traduire du suédois. Il y a fort longtemps, l'île d'Ivö appartenait à Atte Ifvarsson qui était très riche, autoritaire et orgueilleux, apparenté à Ifvar Vidfamne (655-695), originaire de Scanie, un roi semi-légendaire, et plutôt sanguinaire, de Suède, de Norvège, du Danemark et d’une partie d’Angleterre. Atte Ifvarsson vivait dans le château Brattingborg, situé dans la partie du nord de l'île, une place forte bien défendue. Atte et son épouse avaient un fils et une fille. Selon une autre légende, au 12e-13e siècle sur l’île d'Ivö, il y avait, un château et, à quelque deux kilomètres du château, une cave, appartenant à l’archevêque Andreas Sunesson. En 1221, atteint de la lèpre, il est venu passé la fin de ses jours sur cette île. Un jour, il a appris que des brigands sont venus voler une grosse somme d’argent au château Brattingsborg ; ils l’ont dépensée au jeu et en menant grande vie pendant des nuits. Alors l'archevêque a maudit cet argent et, un matin, ils furent très étonnés en constatant que toutes les pièces de monnaie s'étaient transformés en rondelles de pierre représentant une tête-de-mort souriant. [lire dans Svenska Familj Journalen, Bd 13, 1874 - à télécharger en pdf] Ces Brattinsborgspennigen sont citées dans les travaux de numismatique [à télécharger en pdf] ou des brochures touristiques [à télécharger en pdf] ... en suédois ! Les Brattingborgspenningarna scientifiques

p. 121-122 in Nordisk familjebok (a digital facsimile edition from Project Runeberg)

Cliquez sur le texte ci-contre pour lire la page entière >

Isocrania egnabergensis (Retzius, 1781) - à gauche -

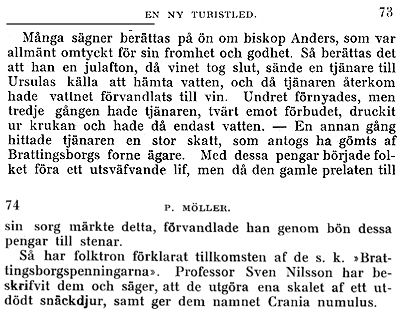

p. 73 et p. 74 in Svenska Turistföreningens årsskrift/1912 (a digital facsimile edition from Project Runeberg)

Systématique et Classification de ces espèces de Craniidés [dont une troisième espèce décrite par von Scholtheim (1820) sous Craniolites brattenburgicus dans un gisement danien à Copenhague (Danemark), elle est citée ici à cause de son nom d'espèce - voir Brunton & Lee, 1986; et Emig, 2009]. Références Brunton C. H. C. & D. E. Lee, 1986. Crania tuberculata Nilsson, 1826 (Brachiopoda): proposed conservation by suppression of Craniolites brattenburgicus Schlotheim, 1820. Bull. zool. nomencl., 43 (2), 215-217. Defrance, E. 1818. Cranie (Foss.). In : Levrault, F G. (ed.), Dictionnaire des Sciences Naturelles. Paris, 11, 312-314. Emig C.C., 2009. Nummulus brattenburgensis and Crania craniolaris (Brachiopoda, Craniidae). Carnets de Géologie / Notebooks on Geology, Article 2009/08 (CG2009_A08), 11 p. [download pdf] von Heijne C., 2005. Fossila ”penningar” från Brattingsborg. Svensk Numismatisk Tidskrift, 4, 90-91 [à télécharger en pdf]. Kaesler R. L. (ed.), 2000. Linguliformea, Craniiformea, and Rhynchonelliformea (part). Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part H. Brachiopoda Revised. Geological Society of America and University of Kansas. Boulder, Colorado, and Lawrence, Kansas, vol. 2, 1-423. Lamarck [J. P. B. A de Monet] de, 1819. Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres, présentant les caractères généraux et particuliers de ces animaux, leur distribution, leurs classes, leurs familles, leurs genres, et la citation des principales espèces qui s'y rapportent; précédée d'une introduction offrant la détermination des caractères essentiels de l'animal, sa distinction du végétal et des autres corps naturels, enfin, l'exposition des principes fondamentaux de la zoologie. Tome 6 (1ère. partie), pp. 237-240, 1-343. Paris. Lee D. E. & C. H. C. Brunton, 1986. Neocrania n. gen., and a revision of Cretaceous-Recent brachiopod genera in the Family Craniidae. Bull. Br. Mus. nat. Hist. (Geol.), 40 (4), 141-160. Linné C. von, 1758. Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata, pp. 1-824 (voir p. 700). Münster, von G., 1840. Description de brachiopodes. In : Goldfuss G. A. Petrefacta Germaniae, 7, 224-312, Arnz & Comp., Düsseldorf. Nilsson S., 1826. Brattenburgspenningen (Anomia craniolaris Lin.) och dess samslagtingar i zoologiskt och geologisk afseendeundersokte. Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar, Uppsala and Stockholm, 324-328 p. Stobæus K., 1732. De nummulo Brattensburgensi singulari illo in Scania fossili, nec non obirer de nonnullis aliis ad hanc historiæ naturalis patriæ partem pertnentibus, inprimis frondosis cornu ammonis cujusdam majoris fragmentis. Londini Gothorum (Dissertatio epistolaris), pp. 1-22, [1-2], pl. [1] [à télécharger en pdf]. Retzius, A. J. 1781. Crania oder Todtenkopfs-Muschel. Schriften der Berlinischen Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde, 2, 66-76. [à télécharger en pdf] |

|

|

Skånes landskapsvapen

Facsimile of p. 25 et 26 Explanation of the Figure

1. Small money of Brattensburg reverse face (supina=bend backwards)

Crania craniolaris

|

Crania craniolaris and the legend of the Brattingsborg pennies |

|

The Brattinsborg pennies (or Brattenbourg or Brattensburg), known in Scania as Brattingborgspenningarna, actually are (ventral) valves of the fossil brachiopod Crania craniolaris, which looks like coins with a skull on one side. Their folksy celebrity is known from the medieval times about their occurrence in Ivö (ou Ovö) island. However, the first scientific interest occurred in the thesis of Stobæus in 1732, but it was his pupil the well-known scientist Carl von Linné who gave, in 1758, a (scientific) name to this fossil specimens. The well-liked Brattingborgspenningarna There are many legends about the “Brattingsborgspengarna”. Two are proposed below which still are told nowadays in Scania. Ida Fredriksson from the “Bromölla Turistkontor” had the kindness to translate them from Swedish. Once upon a time, the island of Ivö belonged to Atte Ifvarsson who was very rich, domineering and proud, akin to Ifvar Vidfamne (655-695), native of Scania and considered as a fabled demigod, rather a bloodthirsty man, king of Sweden, of Norway, of Denmark and of part of England. Atte Ifvarsson lived in the fortified Brattinsgborg castle, located in the northern part of the island. Atte and his wife had a son and a daughter. According to another legend, at the beginning of the 13th century, archbishop Andreas Sunesson spent his last days on the island of Ivö, in his own castle which cellar was about 2 km in the SE of the castle. In 1221, reached leprosy, he spent the end its days on this island. Someday, he found out that warriors have stolen a large quantity of money in the Brattingsborg castle; they have spent gambling and carrying out good life during nights. The archbishop cursed this money and the following morning the warriors was stunned when they found that the coins had turned into stonecoins with a laughing death's-head on. [read in Svenska Familj Journalen, Bd 13, 1874 - pdf download] The Brattinsborgspennigen are cited in numismatisc studies [pdf download] and turist brochures [pdf download] ... in Swedish ! The scientific Brattingborgspenningarna Part below to be translated

p. 121-122 in Nordisk familjebok (a digital facsimile edition from Project Runeberg)

Cliquez sur le texte ci-contre pour lire la page entière >

Isocrania egnabergensis (Retzius, 1781) - à gauche -

p. 73 et p. 74 in Svenska Turistföreningens årsskrift/1912 (a digital facsimile edition from Project Runeberg)

Systematics and Classification of those Craniids species [a third one has been described by von Scholtheim (1820) as Craniolites brattenburgicus in a Danian outcrop at Copenhagen (Denmark), it is refered here according to the species name - see Brunton & Lee, 1986 and Emig, 2009]. References Brunton C. H. C. & D. E. Lee, 1986. Crania tuberculata Nilsson, 1826 (Brachiopoda): proposed conservation by suppression of Craniolites brattenburgicus Schlotheim, 1820. Bull. zool. nomencl., 43 (2), 215-217. Defrance E., 1818. Cranie (Foss.). In : Levrault, F G. (ed.), Dictionnaire des Sciences Naturelles. Paris, 11, 312-314. Emig C.C., 2009. Nummulus brattenburgensis and Crania craniolaris (Brachiopoda, Craniidae). Carnets de Géologie / Notebooks on Geology, Article 2009/08 (CG2009_A08), 11 p. [download pdf] von Heijne C., 2005. Fossila ”penningar” från Brattingsborg. Svensk Numismatisk Tidskrift, 4, 90-91 [download pdf]. Kaesler R. L. (ed.), 2000. Linguliformea, Craniiformea, and Rhynchonelliformea (part). Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part H. Brachiopoda Revised. Geological Society of America and University of Kansas. Boulder, Colorado, and Lawrence, Kansas, vol. 2, 1-423. Lamarck [J. P. B. A de Monet] de, 1819. Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres, présentant les caractères généraux et particuliers de ces animaux, leur distribution, leurs classes, leurs familles, leurs genres, et la citation des principales espèces qui s'y rapportent; précédée d'une introduction offrant la détermination des caractères essentiels de l'animal, sa distinction du végétal et des autres corps naturels, enfin, l'exposition des principes fondamentaux de la zoologie. Tome 6 (1ère. partie), pp. 237-240, 1-343. Paris. Lee D. E. & C. H. C. Brunton, 1986. Neocrania n. gen., and a revision of Cretaceous-Recent brachiopod genera in the Family Craniidae. Bull. Br. Mus. nat. Hist. (Geol.), 40 (4), 141-160. Linnæus C., 1758. Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata, pp. 1-824 (see p. 700). Münster, von G., 1840. Description de brachiopodes. In : Goldfuss G. A. Petrefacta Germaniae, 7, 224-312, Arnz & Comp., Düsseldorf Nilsson S., 1826. Brattenburgspenningen (Anomia craniolaris Lin.) och dess samslagtingar i zoologiskt och geologisk afseendeundersokte. Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar, Uppsala and Stockholm, 324-328 p. Stobæus K., 1732. De nummulo Brattensburgensi singulari illo in Scania fossili, nec non obirer de nonnullis aliis ad hanc historiæ naturalis patriæ partem pertnentibus, inprimis frondosis cornu ammonis cujusdam majoris fragmentis. Londini Gothorum (Dissertatio epistolaris), pp. 1-22, [1-2], pl. [1] [download pdf]. Retzius, A. J. 1781. Crania oder Todtenkopfs-Muschel. Schriften der Berlinischen Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde, 2, 66-76. [download pdf] |

|

|

Qui mangent des Brachiopodes |

|

L'Homo sapiens mange des Lingula : surtout dans le Sud-Est de l'Asie et dans les iles de l'Ouest Pacifique, du Japon en Nouvelle-Calédonie et en Australie, et sur la côte Nord de l'Océan Indien. Trois espèces sont récoltées car elles sont aussi présentent dans la zone intertidale: Lingula anatina, L. reevei et L. rostrum.

Esturgeons, oiseaux de mer, les étoiles de mer sont amateurs de Glottidia, sur les côtes Est et Ouest d'Amérique du Nord et d'Amérique Centrale. D'autres prédateurs se délectent des Brachiopodes rhynchonelliformes : des gastéropodes naticidés et muricidés, les langoustes, des polychètes, des astérides, des poissons... C'est à penser que selon les espèces, elles sont plus comestibles que ne le supposait Thayer (1985). Certes, tous ne mangent pas des brachiopodes mais certains ne les dédaignent pas ! Ce qui laisse à penser que la présence de spicules dans les chairs de certaines espèces ne limite pas le plaisir de les manger. Quelques références récentes... Delance J. H. & C. C. Emig, 2004. Drilling predation on Gryphus vitreus (Brachiopoda) off the French Mediterranean coasts. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 208 (1-2), 23-30. Emig C. C., 1997. Ecology of the inarticulated brachiopods. In: R. L. Kaesler, ed. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part H. Brachiopoda. Geological Society of America and University of Kansas. Boulder, Colorado, and Lawrence, Kansas, Vol. 1, pp. 473-495. Emig C. C. & P. Cals, 1979. Lingules d'Amboine, Lingula reevei Davidson et Lingula rostrum (Shaw), données écologiques et taxonomiques concernant les problèmes de spéciation et de répartition. Cah. Indo-Pacif., 2, 153-164. (disponible en PDF) Richardson J. R., 1997. Ecology of the articulated brachiopods. In: R. L. Kaesler, ed. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part H. Brachiopoda. Geological Society of America and University of Kansas. Boulder, Colorado, and Lawrence, Kansas, Vol. 1, pp. 423-440. Thayer C. W., 1985. Brachiopods versus Musels: competition, predation and palability. Science, 228 (4707), 1527-1528. | |

|

|

Who eat Brachiopods |

|

Homo sapiens eats Lingula: especially in the South-East Asia and the islands of the Western Pacific from Japan to New Zealand and Australia and on the Northern coast of the Indian Ocean. Three species are harvested mainly because present in the intertidal zone: Lingula anatina, L. reevei and L. rostrum.

Sturgeons, migratory birds, starfishes are fond of Glottidia on the East and West coasts of North and Central America. Other species taste also lingulides, i.e., crustaceans (crabs, stomatopods, shrimps, hermit-crab, amphipods), echinoderms (echinoids, ophiurids), fishes... Other predators are delighted by rhynchonelliform brachiopods: gastropods naticids and muricids, lobsters, polychaetes, starfishes, fishes... One may suggest that according to the species, they are more edible than assumed by Thayer (1985). Of course, all do not eat all brachiopods but some enjoy! The presence of spicules in the soft-parts of some species does not seem limiting the pleasure to eat. Some recent references... Delance J. H. & C. C. Emig, 2004. Drilling predation on Gryphus vitreus (Brachiopoda) off the French Mediterranean coasts. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 208 (1-2), 23-30. Emig C. C., 1997. Ecology of the inarticulated brachiopods. In: R. L. Kaesler, ed. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part H. Brachiopoda. Geological Society of America and University of Kansas. Boulder, Colorado, and Lawrence, Kansas, Vol. 1, pp. 473-495. Emig C. C. & P. Cals, 1979. Lingules d'Amboine, Lingula reevei Davidson et Lingula rostrum (Shaw), données écologiques et taxonomiques concernant les problèmes de spéciation et de répartition. Cah. Indo-Pacif., 2, 153-164. (available in PDF) Richardson J. R., 1997. Ecology of the articulated brachiopods. In: R. L. Kaesler, ed. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part H. Brachiopoda. Geological Society of America and University of Kansas. Boulder, Colorado, and Lawrence, Kansas, Vol. 1, pp. 423-440. Thayer C. W., 1985. Brachiopods versus Musels: competition, predation and palability. Science, 228 (4707), 1527-1528. |

S'il existe aussi un Brattingsborg sur l'île de Samsø au Danemark, le Brattinsborg des présentes légendes est situé en Suède dans la la Scanie sur l'île d'

S'il existe aussi un Brattingsborg sur l'île de Samsø au Danemark, le Brattinsborg des présentes légendes est situé en Suède dans la la Scanie sur l'île d'

Mais leur nom scientifique actuel Crania craniolaris (Linné, 1758) leur sera conféré par Retzius, en 1781, dans son travail intitulé "

Mais leur nom scientifique actuel Crania craniolaris (Linné, 1758) leur sera conféré par Retzius, en 1781, dans son travail intitulé "

Elles sont mangées entières (corps et pédoncule) ou seulement le pédoncule. En

Elles sont mangées entières (corps et pédoncule) ou seulement le pédoncule. En